Graham Allison's speech at CCG

Founding Dean of Harvard Kennedy School explores a path away from Thucydides' Trap through U.S.-China strategic concept.

Hi, this is Yuxuan from Beijing. Today, the statement "The 'Thucydides's Trap' is not inevitable" emerged during a dialogue between President Xi Jinping and "representatives from the American business community and strategic academic circles."

Just five days earlier, Prof. Graham Allison, Founding Dean of the Harvard Kennedy School and former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense, who popularized the term "Thucydides's Trap," elaborated on the concept at the Center for China & Globalization (CCG). He reflected on the early interest President Xi showed in the idea, advocating for a new model of major power relations between the U.S. and China that incorporates both cooperation and competition.

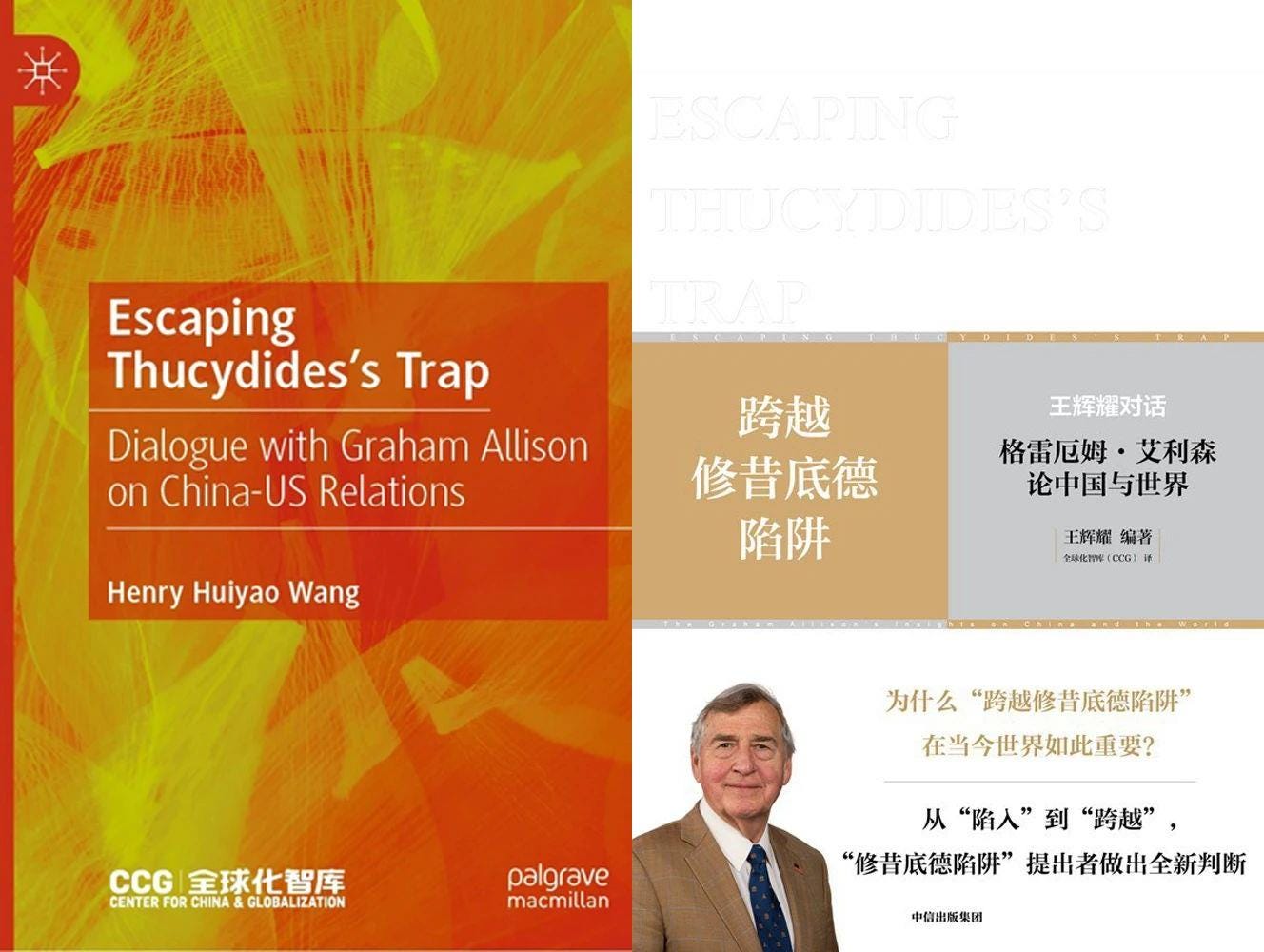

On Friday, March 22, 2024, CCG held a book launch event to release the English edition of the book "Escaping Thucydides’ Trap: Dialogue with Graham Allison on China-US Relations", published by Palgrave Macmillan, as well as its Chinese edition, published by CITIC Press Group. The book launch was followed by an engaging discussion featuring Henry Huiyao Wang, Founder & President of CCG, and Prof. Graham Allison. This was their third collaboration within the CCG's Global Dialogue series, with the previous sessions held in April 2021 and March 2022.

"Escaping Thucydides’ Trap: Dialogue with Graham Allison on China-US Relations" presents a comprehensive collection of Allison’s views and writings on US-China relations from 2017 to 2022, covering a range of topics including the balance of power between the two sides, where the relationship is headed, and lessons from history on how conflict can be avoided. The book also includes an introduction and afterword by Dr. Henry Huiyao Wang, editor of this volume.

The event garnered extensive coverage from multiple media outlets, including Beijing Daily, China News Service, Pheonix TV, Bejing News, China Review News Agency, and China's Diplomacy in the New Era (dplomacy.org.cn). It was also promoted through the official WeChat blog of the Chinese Embassy in the U.S.

To ensure wide accessibility, CCG broadcasted the event live across various Chinese online platforms such as WeChat, Weibo, Douyin, Kuaishou, Baidu, and Bilibili. The video recordings of the event, both in English and Chinese, are available on YouTube and CCG's official WeChat blog.

Prof. Allison's engagement in CCG was part of a productive trip. After the CCG event, he attended the China Development Forum, met with Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi on Tuesday, and on Wednesday, was welcomed by President Xi Jinping.

The CCG Update today presents a transcript of Prof. Allison's speech at the book launch. Please note that the transcript has not been reviewed by Prof. Allison or his staff and may contain errors.

Thank you very much. I think almost everything has been said. I'll try to be brief since you would be interested in the questions and discussion. But let me say a special word of thanks to Henry and CCG and the CITIC for bringing out what I think is a quite remarkable volume. Henry sent me a copy last week in Boston, and I opened it up to look through it. I think I had never quite figured out how you were gonna make this work. But I think you did, because by taking sharp questions and then reading through whatever I've written since Destined for War was published in 2017, and interviews and others, and getting short answers, pithy answers, I think you make a very lively read in just over 100 pages. So I'd say congratulations on the book. For those of you who might have a chance to look at it, I suspect you'll find it interesting. If there is a question that you're interested in. then in two pages or one page and a half, you'll get a short version of the answer. So what I thought I would do was introduce just a few ideas here.

As Henry said, the first actual international leader who picked up the idea and was very interested in it was Xi Jinping. Actually slightly before the book was published, he had become interested in the topic because he and a number of his closest associates had really never paid much attention to Thucydides. And the idea that there was this famous Greek thinker who was roughly a contemporary of Confucius and who had some big ideas, including about patterns in history, he found fascinating. And it's one of his closest associates whom I got to know fairly well in the period after the publication of the book said to me, "Graham, why do you think President Xi Jinping keeps talking about the need for a new form of great power relations?" He said, "Because he has concluded that the old form of great power relations in the rivalries between rising powers and ruling powers have so often led to war."

That's actually Thucydides' big idea. So Thucydides, the founder and father of history, and someone for whom, those of you in the analytic community – if it's not part of your mental library, shame on you – you should meet him, download this book. It's called The History of the Peloponnesian War. It's actually the first-ever history book. It's chock-full of interesting ideas, but one of his big ideas was about what happened that created the Peloponnesian War. And the idea, as he says, was the very rapid rise of Athens, and the impact that had on Sparta, the ruling power at the time, that made the war almost inevitable.

So Thucydides' trap, in a phrase, is the dangerous dynamic that occurs when a rapidly rising power seriously threatens to displace a major ruling power. So the word again, a rapidly rising power seriously threatens to displace a major ruling power.

If we look at the world today, never before in history has a nation risen so fast, so far, on so many different dimensions as China. I mean, you've seen the miracle around you, you've lived the miracle. The country that was poor in which 90% of the people were trying to survive on less than two dollars a day back in the 90s has essentially eliminated abject poverty, and in terms of purchasing power parity, the best metric for measuring national economies, not only overtaken but surpassed the U.S. to have the largest economy in the world. That's in, like, a single generation - never, again, happened before in history. So, a remarkable rise of a remarkable country and culture – the great rejuvenation of the great Chinese people, as Xi Jinping calls it. But the impact of that on a colossal ruling power, the U.S. that basically built the international order after World War II, a quite remarkable international order that has given us 78 years without a great power war – this is historically unprecedented - is inevitably a Thucydides rivalry. So that's the first big idea.

Secondly, and I appreciate the comments by my American colleague from Springer, if there is a war between the U.S. and China, of course, it'll be a tragedy. It'll be a catastrophe. It'll be insane. Indeed, if there's a full-scale war at the end of it, we won't have anything else to worry about, as there won't be this building here, and we won't be here, and there won't be all the buildings at Harvard – they won't be there. Our lives will be over. Our societies will be over. So that's completely insane, I think. But history is full of wars that made no sense; that's why your toast for equality is a good one.

The sense of tragedy though, that the Greek dramatists would say, was not just fate but an inevitable fate, is something that interestingly Thucydides disagreed with. So as he explains in his book, The History of the Peloponnesian War, the reason why I'm taking the trouble to write this book is because I hope we can learn the lesson from what happened here, the mistakes that were made, in order that future statesmen will be able to do better. Well again, that's precisely my objective in the book Destined for War.

So I look, in that book, at the last 500 years. I put the current relationship between the U.S. and China upon the tapestry of history. In the last 500 years, there were 16 great rivalries between the major rising power and the colossal ruling power. Twelve of those ended in war, four of them in no war. So to suggest that war is inevitable would be fatalistic and defeatist. But to say that if all we do is business as usual and all we can manage is diplomacy as usual or statecraft as usual, then we should expect history as usual. And in this case, it could be a war between the U.S. and China; not just a war but a great war; not just a great war but a catastrophic war. So that's the big idea of Thucydides' trap. And what President Xi says - and I believe correctly – is that the notion that this is inevitable is wrong. Thucydides agrees with that and I agree with that.

But in order to avoid Thucydides' Trap, it's gonna be necessary to imagine some new form of great power relations. And when he initially floated this idea - when he was vice president back in 2014 [sic], he left it quite open: what's the content of this? Almost like it was a challenge for folks in the strategic community to work their way around this topic. And I think that remains the challenge that we need to deal with today.

And again, I thank Henry and his colleagues at CCG for pushing this proposition forward in such an imaginative way.

So here's my former professor, then my colleague and friend, and someone with whom I actually co-authored the last piece that he published before he died. This was a Foreign Affairs piece published in October. And Henry (A. Kissinger) left us at the ripe young age of 100 in December [sic. November, 2023]. He was received by Xi Jinping here in July. You may be familiar with that. And it was very gratifying. Xi Jinping was so gracious and warm and friendly. And Henry actually felt like it was kind of a fulfillment in his life in a significant way. And as Xi Jinping here says, you can't think about U.S.-China relations without thinking about Henry.

It was 50 years ago, 51 almost, that Henry came to begin the conversations with Zhou Enlai then basically changed the world - established relations between two great states, relations that have been essential to what we've seen in the world since then, and with lots of interesting clues and lessons from them.

So here's the piece that Henry and I published in October, called The Path to AI Arms Control or the path to some constraints on the potentially most dangerous applications of AI. I would say modestly, it's a pretty good piece. Though it has lots of interesting ideas in it, it was part of actually an effort to encourage the meeting that occurred between Presidents Biden and Xi in San Francisco in November and their conversation about how we can better create a foundation for cooperation between the U.S. and China in the areas that matter most.

But I think, as you can see from these two quotations, Henry alternated between pessimism and optimism, as he says, if you're looking at the recent events, it looks a lot like one of the cases in the Thucydides' Trap casefile that run up to WWI where "neither side has much margin for error" and where disturbance could lead to "catastrophic consequences." "Both sides have convinced themselves that the other represents a strategic danger. We're on the path to great-power confrontation."

We're in the classic pre-WWI situation where neither side has much margin of political concession and in which any disturbance of the equilibrium can lead to catastrophic consequences. Both sides have convinced themselves that the other represents a strategic danger. We are on the path to great power confrontation.

Is it possible for China and the United States to coexist without the threat of all-out war with each other? I thought and still think that it is.

— Henry Kissinger, May 2023

So how did war occur between Germany and the UK in 1914? An Archduke from Austria-Hungary was visiting Serbia and he was assassinated by a Black Hand terrorist who had some association with the Serbian government. That was a spark that produced a fire that was soon a conflagration that essentially burned down the whole of Europe. So how could such a little thing have such a huge consequence? The event was so insignificant that it didn't appear in the newspapers in New York. Probably not in China - I have not looked into that. But within five weeks, all of Europe was in war. So the idea that war makes no sense does not mean war could not happen. The idea that parties who seriously don't want war could nonetheless find themselves in war is a fact from history. So all the more important, therefore, as Henry (A. Kissinger) says, for the U.S. and China to find a way to "coexist without the threat of all-out war." And as he said, he thinks that's still possible.

So here's an assignment for you, if you want to stretch your minds a little bit. Ask yourself, if we had a rational leader in Beijing and a rational leader in Washington (which we actually do). And they're considering, given the conditions today, which should be more compelling? The incentives to compete with the other? Or the incentives to cooperate?

So I gave you a little assignment sheet - no Harvard presentation is complete without an assignment. I would suggest this afternoon when you go home or this evening, take your sheet. And on the first page, "Incentives to compete," if you can't make ten bullet points, you haven't thought hard enough about it. The U.S. and China will be the fiercest rivals of all times, and they will compete for all the reasons of history. And you should be able to work here, list here.

But then turn the page over, exactly the other side, "U.S. vs. China: Incentives to cooperate." So again, we have rational leaders in both countries. And they're asking the question, "Well, what's the checklist of incentives to cooperate?" That may be less obvious if you don't think about it, but I ask you to think about it. And let me give you a clue: if my survival requires me to find a level of cooperation with you, that's a pretty powerful incentive to cooperate. If I face literally an existential threat – "existential" means threat to my existence as a country, that I cannot cope with myself alone without cooperation with you - actually, that sounds like a pretty sturdy, serious incentive to cooperate. And if you work your way down that list, it shouldn't take you very long to think about, "Well, how about a nuclear war?" The end of a nuclear war, Henry (A. Kissinger) once did. As Ronald Reagon taught us, a nuclear war cannot be won - because in the end, your society is destroyed - and must therefore never be fought.

In the climate arena, we now know that we live on a small planet in an enclosed biosphere. Either nation's greenhouse gases go into the same biosphere. So either by itself could, on the previous trajectory, make a biosphere nobody can live in. That's called survival, and that's a pretty powerful incentive. Hence, there are two clues, you should be able to do tick.

So which side? Incentives to compete? Incentives to cooperate? My belief is that the answer is both. It's absolutely compelling to compete; it's absolutely compelling to cooperate. And therefore, the challenge is to somehow keep these two seemingly partially contradictory ideas in our heads at the same time and still function.

Now, in order to try to think about that, as Henry (Huiyao Wang) suggested, the book has not only these but thanks to Henry and the CCG team, you pushed even further. But here are several examples from Chinese history and wisdom, as we try to think about how to escape Thucydides' trap.

The first one that I like very much is the idea of "Rivalry Partners" 竞争性伙伴, which is the way that the relationship between the Song and the Liao is often characterized as they were fierce rivals but neither was able to defeat the other. In the Chanyuan Treaty about 1,000 years ago, they agreed to be "Rivalry Partners." In some arenas, they would be fierce rivals; in other arenas, they would be thick partners. And that treaty provided peace for only 120 years. A lot would say, in history, that's a pretty good record.

The second idea, which you all are familiar with much more than I am – most of you – is the Sun Tzu story about Wu and Yue. So here are two deadly adversaries. They are on a ship; the ship sinks. They're prisoners and they're gonna be taken to a prison. Ship sinks and the two of them escape. And they get into a small rowboat – just the two of them. But the rowboat is too wide for either of them to hold both oars. So if only one can row, this little rowboat goes around. So, in order to get to the shore to survive, they have to cooperate. That's a pretty compelling reason to cooperate.

Xi Jinping added a whole new idea to this at the meeting that Henry (Huiyao Wang) already referred to with the Senator Chuck Schumer and others, and surprised them. Actually, this is a phrase I had never seen or heard before. He said to them, "I am in you, and you are in me." Seriously, what does that mean? A Chinese will understand it better than an American. And the senators, do they know how to interpret this? But the idea that "I am in you, and you are in me," well, that's a level of complexity and subtlety that escapes most Americans who were more simplistic. So we like more things black and white or "either-or," but I think correctly, life is more complicated. So I think it's a very interesting idea there.

And then finally, you are familiar with "Yin/Yang" - ideas in, again, Chinese civilization of having contradictions between theses and antitheses that get resolved in the synthesis which then leads to the next round. But again, levels of subtlety and complexity.

So just to conclude, what the book does is begin struggling with the notion: How to escape Thucydides's Trap. It does not have a fixed solution. Indeed, I think what's happening currently, as you can see both in the American government and in the Chinese government, is people are stretching for what Kissinger called a "strategic concept." It's a concept that will help us understand how you can both be competing and cooperating at the same time. That was something that Kissinger and Xi Jinping talked about in their meeting in August; It's one that Henry (A. Kissinger) kept stretching for. I think nobody yet has got a picture that works, but I think this is a way of stimulating imagination. And I think the challenge over the next period will be for leaders in both countries to find ways of both conceptualizing this and then operationalizing it in their policies.

So to end on an up note, I would say the good news for me about what's happened in U.S.-China relations recently, which was already referred to, was what was achieved by Presidents Xi and Biden in San Francisco, in which they demonstrated that two rational leaders can sit down and talk at great length, privately, candidly, without this becoming public, about the things that matter than the most, including that war between the two countries, would be catastrophic (and each of them understands it), about the ways in which that may happen, for example, over Taiwan, and about what actions they would take to ensure that doesn't happen.

So what was done there, I think, not just put a floor under what was previously a spiraling deteriorating relationship, it actually produced a foundation, a pretty stable foundation on which we can now build something sustainable. But again, in doing that, we're gonna have to conceptualize this set of seeming contradictions.

So again, to conclude, I would just say, Henry (Huiyao Wang), thanks to you and CITIC and the team for an impressive product. And I look forward to the continuing discussion.