The Short Age of China’s Long Change

Liu Yuanju shows how the familiar world around us is barely decades old, and why that makes it precious—and precarious.

China’s everyday “normality” can feel deceptively old—for those born later than the 1990s at least: safe streets, two-day weekends, basic welfare, passports on demand, and Hollywood blockbusters. But as Liu Yuanju, research fellow at the Shanghai Institute of Finance and Law, stitches together the timeline of China’s compressed modernity, comforts now treated as timeless emerge as fragile gains of just a couple of decades. His piece is a reflective reminder that the past is indeed a foreign country, and that any serious conversation about China’s future needs a clearer memory of how recently this “normality” was built.

The article was first published on FT Chinese, the Chinese-language service of the Financial Times, on 21 June 2024, although we have only just come across it recently. Both FT Chinese and Liu have kindly authorised a translation, but have not reviewed the following text.

—Yuxuan Jia

When I first commissioned this piece, Yuxuan joked that it felt rather “gongzhi”—a label sometimes in China to describe writing that instinctively cherishes economic reform, market openness, and the possibilities unlocked by a freer, more expansive society. Perhaps. But what struck me, and may resonate with readers elsewhere, is something simpler and more human: that a country capable of changing this much, this quickly, inevitably carries within it many forms of disorientation—material, psychological, institutional, even spiritual. What appears uneven, contradictory, or insufficient today is not always a matter of intention or ideology; sometimes it is merely the consequence of modernity arriving in a rush, before society has had the time to absorb it fully.

China’s everyday normality—its safety, mobility, insufficient welfare, and cultural horizons—was not inherited but assembled, often painstakingly, within a few short decades. The tensions and anxieties visible now are, in part, the shadows cast by that compressed ascent. To see this clearly is not to romanticise or excuse, but to understand: nations, like people, need time to metabolise change, to let new habits settle into deeper foundations.

And perhaps that is the quiet truth running beneath Liu Yuanju’s essay: that what was built so swiftly can also be fragile—that the very speed of these gains invites us to ask how easily they might be lost, and how much care is needed to sustain them.

—— Zichen Wang

你所熟知的时代,才开始没多久

The Era You Know Hasn’t Been Around for Long

Introduction

Good times haven’t been around for long, so they’re worth treasuring. Older generations need not romanticise their youth into a golden age, and younger ones shouldn’t expect yesterday’s fixes to sort out today’s problems. The only viable direction lies ahead.

In the initial stage of reform and opening up in 1978, China’s GDP started from a low base of US$149.8 billion, with an average annual nominal growth rate of around 10 per cent. However, growth was volatile, held back by the legacy of the planned economy, the pains of state-owned enterprise reform and international sanctions in the early 1990s. By 1996, GDP had reached US$856.4 billion, 4.7 times its 1978 level, but the slope of the growth curve was already flattening. It was not until after China joined the WTO in 2001 that the economy really began to surge.

That was the real opening of a new era, and it was not very long ago.

01

China is often described as a very safe country today, but that reality is relatively new.

Not long ago, criminal gangs made up of young men from Wenjiang Village, Tiandeng County, in Guangxi were carrying out robberies across large parts of Guangdong, using brutal methods such as hacking at victims’ hands and feet. Between 2000 and 2011, more than 100 members of these gangs were arrested or executed; in 2004 alone, over 40 young men from the village were arrested in Shenzhen.

At the time, an 18-year-old villager told police, cavalierly, “There are plenty of people from our village who go out robbing. I’m actually one of the latecomers.”

After 2000, so-called “hand-chopping gangs” repeatedly appeared in Guangzhou, Shenzhen and other cities. Many of these violent groups came from Tiandeng County in Guangxi. Their methods were exceptionally savage: when they went after mobile phones or other valuables and a victim tried to resist, they would use a sharp blade to cut off the person’s arm, scarring countless lives and doing enormous damage to society.

Besides the so-called “hand-chopping gangs”, “motorcycle theft gangs” also loom large in many people’s memories.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, across the Pearl River Delta, these gangs roamed the streets on motorbikes, robbing and stealing, their very name being enough to send a chill down the spine.

In May 2006, for instance, Zhong Nanshan, the renowned respiratory expert in the fight against SARS and COVID-19, had his laptop bag snatched.

That year, many Guangzhou residents saw plainclothes officers racing through traffic in hot pursuit of motorcycle snatchers. Security patrols in the city were equipped with special hooked poles, designed specifically to bring down their bikes.

By then, motorcycle theft gangs had already seriously undermined public security in the Pearl River Delta. On 1 January 2007, Guangzhou brought in a blanket ban on motorcycles. Before the ban, some 200,000 motorcycle-taxi drivers in the city depended on their bikes for a living; the policy forced them into other lines of work, and the motorcycle-taxi trade has never recovered since.

Once deprived of the very environment that had sustained them, these motorcycle theft gangs gradually faded from view.

World Bank research suggests that once per capita GDP passes around US$12,000, rates of property crime begin to fall, underlining that public safety is, at heart, about how the gains of development are shared. In the end, it is economic development that makes societies safer.

If 2007, the year Guangzhou introduced its motorcycle ban, is taken as a starting point, this level of safety—where people can sit at a street barbecue past midnight without worrying about being robbed—has existed for only 18 years.

In recent years, though, fraud targeting older people has become increasingly common and often involves large sums; in some cases, the average loss per victim has exceeded 80,000 yuan [US$11,255].

02

For those born in the 1970s and 1980s in rural areas, the experience of the rural collective accumulation system is still very vivid.

One example is the so-called “three deductions”, the village retention system under which village-level collective economic organisations withheld part of farmers’ income to cover three categories of spending: a public accumulation fund, a public welfare fund and management expenses.

Another is the “five pooled funds”, a township-level pooling system. Township cooperative economic organisations collected money from subordinate units and rural households to finance local public undertakings at the township and village levels, including schooling, family planning, support for entitled groups, militia training, and the construction of rural roads.

For most farmers, the “three deductions and five pooled funds” were a heavy financial burden. In 1998, a household with four mu of land had to pay 204 yuan under this system—about 51 yuan per mu—on top of delivering 263.5 kilograms of grain (around 65.875 kilograms per mu) as quota to the state. Valued at the then market price of wheat, 1.2 yuan per kilogram, that quota came to roughly 632 yuan. Together, these payments swallowed about 15 to 20 per cent of a farmer’s cash income. For families already struggling with poverty or paying children’s school fees, the pressure was even greater.

It was not until 2002 that these levies were finally scrapped.

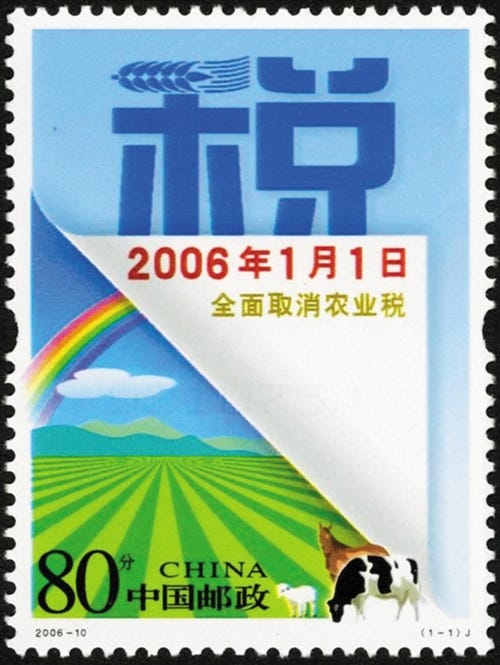

On 22 February 2006, a 0.8-yuan commemorative stamp titled “Complete Abolition of the Agricultural Tax” was issued, embodying the formal end of China’s agricultural tax system.

A traditional tax that had endured in China for some two millennia ended only 19 years ago.

03

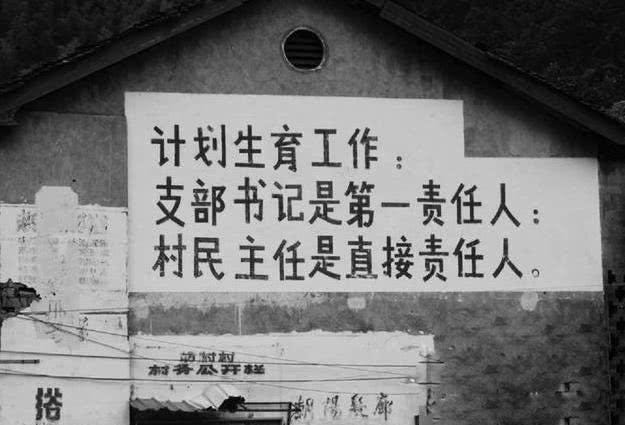

In those years, village levies and the enforcement of family-planning rules were the main sources of tension in rural China. The disappearance of forced late-term abortion from everyday life is also a relatively recent change.

In the 1980s, provincial family-planning regulations across China generally required that any pregnancy outside the approved plan be terminated. In other words, no matter how far the pregnancy had progressed, it had to be ended; if it was already in the later months, that meant a forced late-term abortion.

By the 1990s, however, this kind of wording had been removed.

Another decade slipped by, and the Population and Family Planning Law, implemented in 2002, finally set a clear legal standard: “People’s governments at all levels and their staff members must strictly administer in accordance with the law and enforce policies in a civil manner when carrying out family-planning work, and must not infringe upon citizens’ lawful rights and interests.” Only then was late-term abortion formally banned in legal terms.

In practice, though, cases of forced late-term induction were still being reported as late as 2012.

04

At the time, a popular phrase captured the mood in the countryside: the agricultural tax was gone, and the minimum-living allowance had arrived.

With the minimum-living allowance system in place, anyone could secure basic subsistence and no longer faced the risk of starving. Of course, the system also drew in its share of people who learned how to work the rules.

By 1999, the minimum-living allowance had been rolled out across the map: all 668 cities and 1,638 towns serving as seats of county governments had set up schemes. This laid the groundwork for extending the minimum-living allowance system to rural areas and, after 2014, for integrated urban and rural insurance. It also helped push China’s welfare model away from “employing institution-based protection” and towards a system of social security.

The minimum-living allowance was first applied to laid-off urban workers in 2002, while the rural minimum-living scheme did not achieve nationwide coverage until 2006.

Basic medical insurance arrived on a similar timeline. The first nationwide scheme—Basic Medical Insurance (BMI) System for Urban Employees—was launched in December 1998, meaning it has been in place for only 27 years, and from the outset, it covered only those with formal jobs. The scheme for urban residents without formal employment, Urban Residents-Based Basic Medical Insurance (URBMI), was only rolled out nationwide twelve years later in 2010, meaning it has been in existence for merely fifteen years.

Once basic medical insurance and the minimum-living allowance were in place as a basic safety net, attention naturally shifted to another major pillar of people’s wellbeing: education.

Even today, people still toss out the line “we have all received nine years of compulsory education” in the middle of an argument, yet the person on the receiving end may never have had the chance to enjoy genuinely free schooling.

China’s nine-year compulsory education programme began on 1 July 1986. Although the Compulsory Education Law stated that “no tuition fees shall be charged,” the Implementing Rules for the Compulsory Education Law introduced an article allowing schools to collect “miscellaneous fees” for items such as textbooks and exercise books, creating a system that was nominally fee-free but in practice still required payments. A 1990 spot check by the State Education Commission found that miscellaneous fees at rural primary schools averaged 48 yuan a year, roughly one-third of a farmer’s average monthly income at the time. For many children, those costs were still high enough to shut the school gate in their faces.

An example of economic punishment appeared in a 1989 report by China’s Farmers magazine, which described a primary school in Henan where children were made to copy out their textbooks ten times for every day they were late paying miscellaneous fees. At the time, many students, especially in rural areas, faced corporal punishment or forced copying because their families could not afford these charges.

Compulsory education did not become genuinely free of both tuition and miscellaneous fees until 2006, and that system has been in place for only nineteen years.

Today, when education comes up, many people are quick to rail against learning English, yet the history of English as a subject taught universally in China is actually not very long.

In 1950, the Ministry of Education’s Decision on Foreign-Language Instruction in Secondary Schools designated Russian as the first foreign language. By 1956, China had 12,000 secondary-school Russian teachers, accounting for 87 per cent of all foreign-language teachers nationwide.

After the Sino–Soviet split in the 1960s, English began to replace Russian as the main foreign language. It was not until after 1983 that English was put on the same footing as Chinese and mathematics in the national university entrance examination.

And as the economy developed, protections for basic livelihood rights improved, and space for individual freedom expanded with it.

05

The 1949 Common Programme of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference stipulated that “public and private enterprises shall generally implement an eight- to ten-hour working day,” but it did not specify the working days per week.

The State Council’s 1952 Decision on Labour and Employment Issues effectively established the practice of an eight-hour workday and a six-day workweek, with Sunday as the only statutory day of rest.

Before the 1990s, urban residents referred to Sunday as “the fighting Sunday,” a day on which they had to concentrate all their shopping, laundry and other household tasks.

Before the 1994 reform, Chinese workers on average put in about 400 more hours a year than the standard set by the International Labour Organisation. Change only came when the State Council issued Order No. 146, Regulations on Working Hours for Employees, on 3 February 1994, introducing, from 1 March, an eight-hour workday and an average forty-four-hour workweek. This “alternating weekend” system meant two days off in one week and one day off in the next, in effect creating a five-and-a-half-day workweek.

This turned the two half-days of rest in every two-week cycle into one extra full day off, the arrangement commonly known as the “big week–small week” schedule. Under this system, workers rested on both Saturday and Sunday in the first week, but only on Sunday in the second.

On 25 March 1995, the State Council issued Order No. 174, revising the Regulations on Working Hours for Employees and stipulating that, from 1 May 1995, a standard schedule of eight hours a day and forty hours a week would apply, the system commonly known as the two-day weekend.

The two-day weekend has, in fact, been in place for only thirty years. Anyone born before the 1990s would have known the grind of six-day workweeks, whether in the workplace or at school.

But once people finally had more leisure time, the natural impulse was to get out, travel and see more of the world.

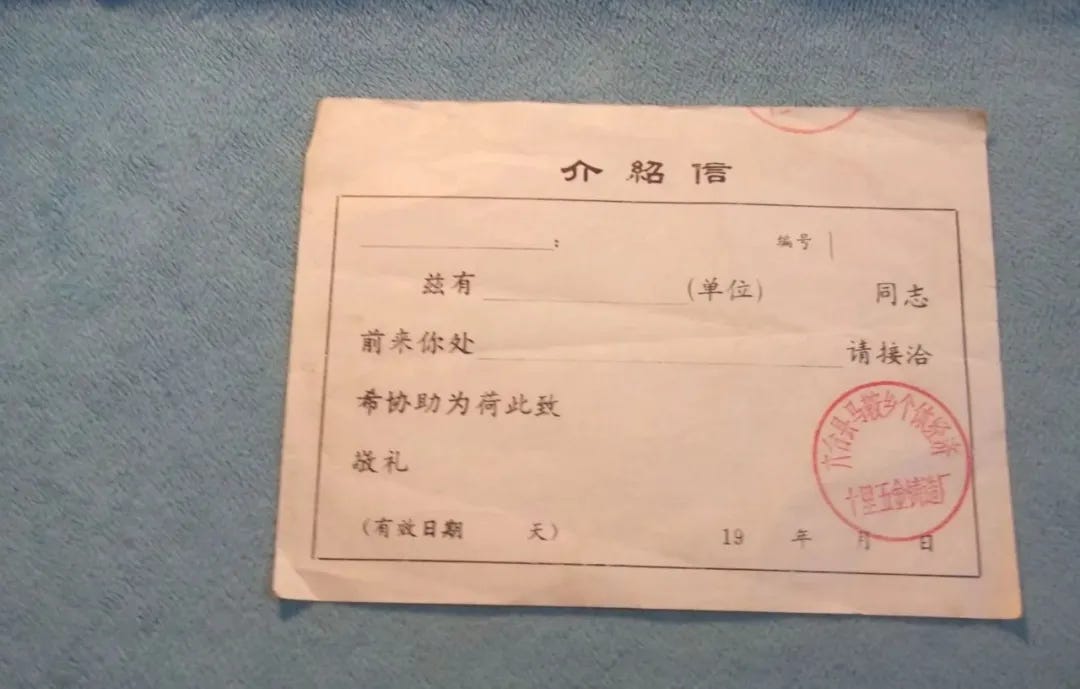

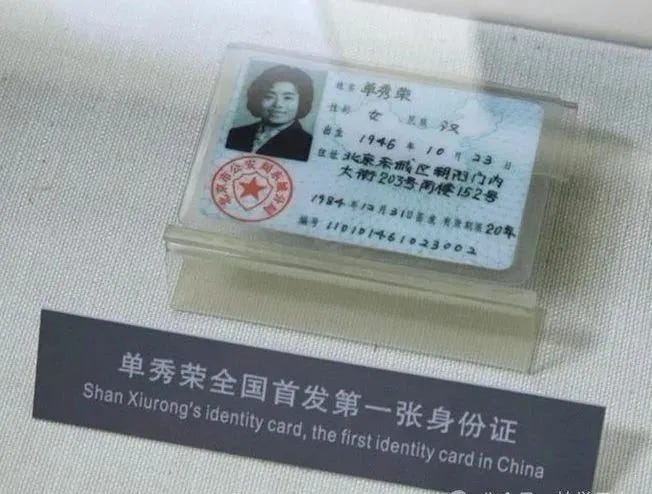

Before the nationwide roll-out of the identity card system in 1995, Chinese citizens relied mainly on letters of introduction issued by their employing institutions or neighbourhood offices when travelling, checking into accommodation, or handling official paperwork. These letters functioned as a kind of pass. Getting one from an employing institution or local police station meant stating clearly where the holder was going and why—information an identity card does not require.

The identity card system widened the space for personal freedom in China, yet it has been around for only about thirty years. Yes, even someone who is thirty today once lived at a time when letters of introduction were still part of everyday life.

But an identity card on its own was far from enough.

On the evening of 17 March 2003, Sun Zhigang, a 27-year-old from Hubei, was stopped by police in Huangcun, Tianhe District, Guangzhou, for not carrying his identity card, a temporary residence permit or an employment certificate. Classified as an “undocumented and unregistered” person, he was taken to the Huangcun police station. A colleague later arrived with his ID card and asked for his release, but the police refused, citing an ongoing “Strike Hard” campaign.

On the night of 19 March, after calling for help and angering several attendants, Sun was beaten repeatedly by staff and other detainees. He died the next day, 20 March, from traumatic shock. Once the case was reported by the media, it sparked nationwide outrage.

On 1 August 2003, China formally abolished the Measures for Internment and Deportation of Urban Vagrants and Beggars released in 1982, and, at the same time, introduced the Measures for the Administration of Relief for Vagrants and Beggars without Assured Living Sources in Cities. The change marked a basic shift from compulsory custody and repatriation to a system built around voluntary assistance.

Today, many young people talk about just taking off whenever they feel like it — to wander, to “let their soul drift,” to live as gig workers. The simple fact that someone can choose that kind of life without being rounded up for compulsory labour has existed for barely more than twenty years.

Once identity cards were in widespread use and the risk of being taken into custody receded, domestic tourism began to take off.

In earlier decades, most people only travelled when sent away on business. In 1999, the introduction of the May Day and National Day “Golden Weeks” gave an enormous boost to domestic tourism, which kept growing and gradually became a way of life for many Chinese. All this has been part of ordinary life for only a little over twenty years.

That generation not only criss-crossed the country to see China’s great landscapes; it also began to look outward and dream of seeing the wider world.

Not long after, though, 1994 became a major turning point in how private overseas travel was managed. That year, the Ministry of Public Security standardised application procedures for private passports, but tight controls still applied, and going abroad usually meant joining an organised tour group or securing other special arrangements.

After China’s accession to the WTO on 11 December 2001, the country moved quickly to reform its exit–entry regime and bring it closer to international practice. Within just ten days of accession, several new measures were piloted or rolled out, marking a new stage in China’s opening to the outside world and signalling the beginning of the end for the approval-based passport system that had been in place since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949.

Five years later, in 2006, more than 200 large and medium-sized cities had adopted a system of issuing passports on demand.

Wang Sicong, the only son of business tycoon Wang Jianlin and perhaps China’s most notorious rich kid, once scoffed, “It’s already 2020 — how can anyone still not have been abroad?” Yet even for someone with his wealth, the freedom to decide on a whim to fly to London and feed the pigeons has existed for no more than nineteen years.

06

Wang Sicong was born in 1988. He may even retain a faint memory of ration coupons. The ration-coupon system remains part of China’s collective memory: grain coupons, grain ration books, oil coupons, meat coupons, bicycle coupons, liquor coupons and more.

The older generations lived through it; the younger ones had at least heard about it. Most people now tuck it away in the mind as something belonging to a far-off era. Yet that instinctive sense of distance is misleading.

On 1 April 1993, the State Council’s Notice on Accelerating the Reform of the Grain Circulation System came into effect, bringing to a complete end nearly forty years of grain and oil ration coupons and completing the shift to a market-based, open supply of these staples.

When the wave of online entrepreneurship surged through China in the early 2010s, public debate often hailed the post-1990 generation as “digital natives”—children of material abundance, raised amid explosive technological change, untouched by scarcity and naturally predisposed to innovate.

But this collective memory is off the mark. Strictly speaking, they still belong to the ration-coupon generation.

In December 2001, Shanghai General Motors launched the Buick Sail, a compact car priced at around 100,000 yuan. Marketed for its “safety, environmental performance, and affordability,” it sparked a nationwide wave of excitement about private car ownership and was widely hailed in the media as the “year one” of China’s household automobile.

Soon after, joint-venture models such as the Buick Excelle and Hyundai Elantra began to edge out the more official-looking Santana.

It has been only twenty-four years since owning a car became a common aspiration for ordinary Chinese households.

07

As material life improved, cultural and spiritual horizons widened too.

Between 1949 and 1976, China imported foreign films mainly through a non-commercial buyout model: copyrights were acquired via intergovernmental cultural exchanges or film-exchange agreements, with a one-off payment of about US$20,000 per title.

The price was so low that it rarely attracted top-quality films; what arrived were often minor works or titles that had already been in circulation for many years.

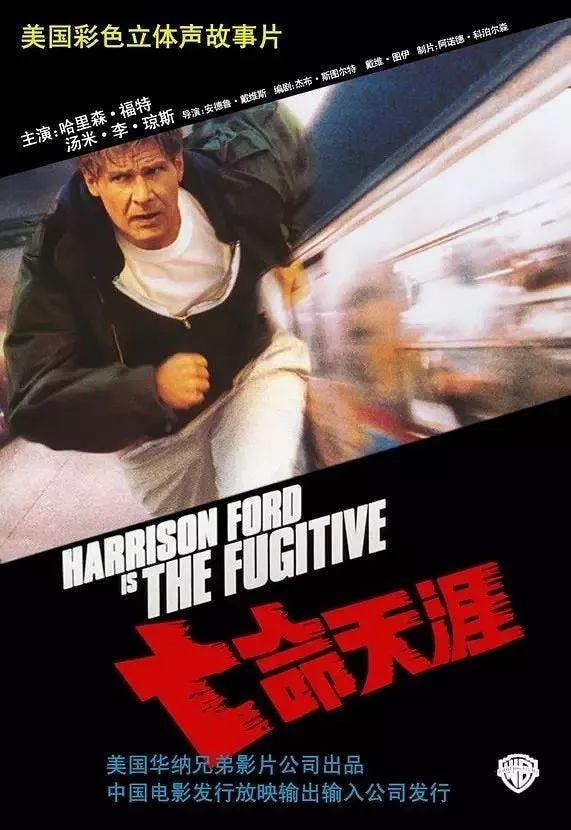

By 1994, China’s film market had slumped into a deep recession. Annual cinema attendance had collapsed from 29.3 billion admissions in 1979 to just 4.2 billion, leaving the industry fighting for survival. In this context, Wu Mengchen, then general manager of China Film Group Corporation, put forward a proposal to bring in first-run foreign blockbusters under a revenue-sharing model.

At the end of 1994, a pivotal reform—the policy of importing ten revenue-sharing foreign blockbusters—was formally introduced. Approved by the Film Bureau of the Ministry of Radio, Film and Television, it stipulated that each year ten foreign films meeting two “broad criteria” [films that broadly represent the best of world civilisation and contemporary film art and technology] would be imported on a revenue-sharing basis.

In November 1994, The Fugitive, starring Harrison Ford, became the first foreign film imported into China under the revenue-sharing model. Shown on a pilot basis in six cities—Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Chongqing, Zhengzhou and Guangzhou—it achieved cinema occupancy rates of more than 80 per cent and took in 25 million yuan at the box office. Families went to the movies together, companies and institutions booked out entire theatres, and the film delivered the first true box-office sensation of imported films.

Many of the titles that followed remain etched in the childhood memories of the post-1990 generation: Arnold Schwarzenegger’s True Lies, Keanu Reeves’s Speed, the animated classic The Lion King, and others.

In reality, Chinese audiences have been able to see foreign films in any real volume for only a little over thirty years.

08

Although almost everything today seems to be in flux, the underlying drivers look remarkably familiar: the long arc of reform and opening up, and the burst of expansion that followed China’s accession to the WTO. As the market economy took shape, GDP has become a term known by almost every Chinese person.

From 1952 to 1981, China used the Soviet-style Material Product System (MPS), a national accounting framework designed for a planned economy. Until the 1980s, this system was the sole benchmark for China’s macroeconomic management.

After 1981, China began to experiment with the System of National Accounts (SNA), launched dedicated research in 1984, and formally switched to GDP-based accounting in 1992. That shift marked an institutional turn away from the planned-economy model and toward a market-oriented one.

The adoption of the term “GDP” has had far-reaching effects on Chinese society.

Under the MPS, only labour that produced material goods or added value to those goods counted as “productive.” The material-production sectors, in this sense, were commerce, industry, agriculture, construction and transport.

The MPS, however, was unable to capture the rise of non-material services that took off after reform and opening up: finance and insurance, real estate, scientific research, education and culture, healthcare, and household services.

GDP and the MPS, in that sense, sit at the root of today’s debate over the “real” and “non-real” economy. Yet those non-material services are plainly essential to people’s quality of life.

As Steven N. S. Cheung has argued, China’s economic development has been driven by competition among counties. In a certain sense, it was only after GDP was adopted as an official metric in 1992 that ordinary people’s well-being more fully became a performance target for local governments.

All these transformations grew out of reform and opening up, and especially out of the wave of globalisation that followed China’s accession to the WTO. Only by deepening that process—by continuing to look outward to the wider world and to humanity as a whole—can such changes be sustained.

Many of the things taken for granted today have not been around for long, yet already feel as if they belonged to some distant age. Perhaps that is because memory is so selective, or because the past is so often bathed in a softer, more flattering light.

Anyone born into a particular era, from the moment memory begins, tends to treat the life around them as natural and self-evident. Later in life, though, youth is easily polished, embellished, and remembered as far more beautiful than it ever was.

For this reason, both the young and the old often lack a true sensitivity to the blessings of the present. Yet only by understanding where a society has come from can it gain a clear sense of where it ought to go.

Good times haven’t been around for long, so they’re worth treasuring. Older generations need not romanticise their youth into a golden age, and younger ones shouldn’t expect yesterday’s fixes to sort out today’s problems/

The only viable direction lies ahead—only then can we, our children, and our children’s children have a better future.