A glimpse into the ongoing "zero-based budgeting" fiscal reform in Anhui

A fascinating on-air confession by a provincial govt on its fiscal spending and the way forward

China Central Television, the state broadcaster, aired a fascinating three-episode video report between October 12 and 14 to showcase the implementation of zero-based budgeting, a budgeting process that allocates funding based on program efficiency and necessity rather than budget history, in central Anhui Province, where I was born and raised.

The newly minted buzzword took up just one sentence in the Resolution of the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in July.

Reforms for zero-based budgeting will be advanced.

The Ministry of Finance reposted the three episodes and their transcripts [1] [2] [3] on its website and WeChat blog, so the MoF fully backs the reform and report.

In today’s newsletter, I’ll walk you through the first episode of the report. All emphasis in the transcript is mine. I’ll share some thoughts at the end.

A Reform of Abolishing the Old and Establishing the New: Anhui Targets Ineffective Fiscal Spending

Narrator: What is zero-based budgeting reform? Simply put, it is a change in how financial funds are allocated. For example, if a department had a budget of 10 million yuan last year, it was highly likely that this year’s budget would be based on that figure and adjusted upwards. However, this “baseline” no longer exists after the reform, and everything starts from zero. Suppose a department wants to apply for a budget now. In that case, it first needs to consider whether the tasks are vital priorities the central government promotes and whether they can bring new momentum to the industry. The finance department will then compile the budget based on actual needs, considering factors such as financial resources and priorities. This reform will affect the entire system and break the established interest structures.

A Surprising Discovery in Stocktaking

Narrator: At present, Anhui Province is rolling out this reform across the province. Will the reform go smoothly? What impact will it have? The zero-based budgeting reform in Anhui started with a stocktaking. Behind every policy that spends money is a project that requires financial support. How many policies are there? What is the total amount of financial support involved? What is the status of fiscal spending for these projects? No one knew before the stocktaking, and the results shocked everyone.

Li Qiuhuai, a staff member from the General Office of the Anhui Provincial Government: After we consolidated the policies, we were stunned because there were so many policies. It was beyond our imagination.

Narrator: Li Qiuhuai’s division led the stocktaking for Anhui at the provincial level. Together with the provincial government’s finance department, they spent over a month compiling a thick policy list covering various departments, from supporting technological innovation to promoting industrial development, from talent support to infrastructure construction. There were as many as 328 items in total.

Problem 1: Overlapping Subsidies, Different Standards

Li Qiuhuai, a staff member from the General Office of the Anhui Provincial Government: Each department funds the same policy from different angles, leading to duplicate subsidies for the same policy.

Zuo Zizhi, Deputy Director-General of Anhui Provincial Government’s Finance Department: Everyone wants to support this technology. The Science and Technology Department wants to support it, the Development and Reform Commission wants to support it, and the Industry and Information Technology Department wants to support it. You set up your support, I set up mine, and in the end, one project receives duplicate support. Why is it inefficient and ineffective? Because the information between departments is not shared.

Problem 2: Policies Not Coordinated, Resulting in Inefficiency

Narrator: On the list, reporters counted eight policies supporting breakthroughs in science and technology research involving different departments. This kind of overlapping policy also exists in rural affairs.

Zuo Zizhi, Deputy Director-General of Anhui Provincial Government’s Finance Department: For example, in the “construction of beautiful villages,” the transportation department may build a road in the west, the water conservancy department may dig a canal in the east, the forestry department may plant trees in the south, and even the housing and urban development department may build urban infrastructure in the north. Why is so much work inefficient and ineffective? That’s the problem. Every department completes its task, but there is no result when you look at reality.

Problem 3: The Existence of “Zombie” Policies

Narrator: Moreover, during the cleanup, they discovered many “zombie” policies—expired policies but were still in a “pending settlement.” Some policies, for example, were issued in the 1990s but are still being implemented.

Zuo Zizhi, Deputy Director-General of Anhui Provincial Government’s Finance Department: For example, there was a 28.5 million yuan policy to support small towns. This was an old policy from 30 years ago. We have 104 counties and districts, and the number of small towns [under these counties and districts] is unimaginable. What impact can this 20 million yuan have when divided among them?

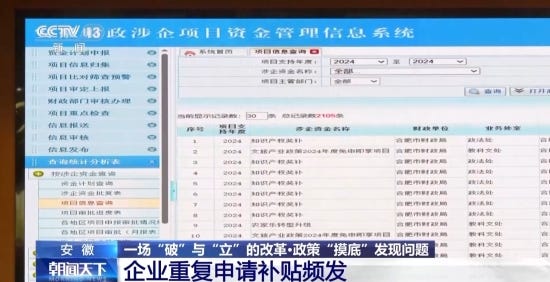

Problem 4: Enterprises Frequently Duplicate Applications for Subsidies

Narrator: Each department manages its jurisdiction with little coordination, which has led to a new problem: businesses exploiting loopholes to “rewrite” project proposals to apply for subsidies. This issue is particularly evident in the industrial sector. Through the [Anhui Provincial Government’s] finance department’s information system, it is clear that in the past two years, many businesses have been able to apply for subsidies from multiple departments simply by “refreshing” a project proposal.

Wang Xu, Director of Budget Performance Division, Anhui Provincial Government’s Finance Department: For example, when applying for a project, businesses submit the same project to multiple departments or apply for multiple projects within the same department to receive duplicate subsidies.

Wu Jinsong, Secretary of the Party Committee of Anhui Provincial Science and Technology Department: A project can be submitted to six departments. The project proposal is slightly modified and submitted to the Industry and Information Technology Department today, the Development and Reform Commission tomorrow, and the Science and Technology Department the day after tomorrow. Multiple submissions result in researchers focusing more on administrative matters than research. More importantly, everyone is doing small projects, not big projects. A lot of money is spent, but problems remain unsolved.

Abolishing the Old Pattern! Cutting the “Cake” Again with the “Blade Turned Inward”

Narrator: During the large-scale stocktaking, the Anhui Provincial Party Committee and the provincial government discovered overlapping subsidies for some policies, multiple departments involved in one task, and certain policies that have been delayed too long. The ineffective use of fiscal funds can be eliminated only by cleaning up policies. Anhui is determined to “abolish the old” first before “establishing anew,” starting with policy cleanup. However, the first step of “abolishing” is extremely difficult.

Li Qiuhuai, Anhui Provincial Government Office staff member: The process of ‘abolishing the old’ is very difficult. Which policies should be abolished, and which must be safeguarded? Every department has its own opinion. So at this point, we were faced with a challenge, and when the [stocktaking is over and the] list came out, the work [of zero-based budgeting reform] was immediately stalled.

Duan Changpu, Director of Major Tasks and Strategic Science and Technology Power Construction Division, Anhui Provincial Science and Technology Department: There are definitely some obstacles to integration, especially in mindsets.

Xin Xin, Deputy Director of the Technological Reform Division, Anhui Provincial Industry and Information Technology Department: With any reform, there will be an adaptation period. At first, it might not be fully understood, but people’s thinking has to shift.

Narrator: How did the reform break the ice? Li Qiuhuai told reporters that this list, which drills down to the minor policy “granules,” acts like a mirror, reflecting how each department implements policies and whether they are scientifically sound. Several closed-door academic seminars were held around the advancement of the reform.

Li Qiuhuai, staff member of the Anhui Provincial Government Office: The provincial governor, vice provincial governor, and the heads of the key provincial departments all gathered to discuss: Should we push forward with zero-based budgeting? How should we do it? In our department, how can we take the lead in zero-based budgeting? Everyone engaged in intense and heated discussions.

China Central Television reporter Wang Nan: Reform implies a redistribution of interests, and reaching a unified consensus is not easy. In this large classroom at the University of Science and Technology of China’s International Finance Institute, provincial leaders, provincial department heads, and city and county leaders held a full-day discussion on zero-based budgeting reform. During this discussion, an official from the provincial Development and Reform Commission suggested that they could abolish one policy involving approximately 800 million yuan.

Zhong Lan, Anhui Provincial Development and Reform Commission Deputy Director-General: This policy may not align well with the current central work of the provincial Party Committee and provincial government or with the current development requirements.”

Narrator: After multiple rounds of in-depth discussions, more and more departments reached a consensus, and the large-scale policy cleanup work began.

Zuo Zizhi, Anhui Provincial Finance Department Deputy Director-General: “Policies without vitality lead to projects without benefits, which is the biggest waste. For example, the fiscal funds for supporting the construction of small towns must be pulled back. So, we abolished that policy.”

Narrator: Not only were some policies abolished, but spending over many ineffective policies were significantly cut.

Zuo Zizhi, Anhui Provincial Finance Department Deputy Director-General: The largest reductions were in support of industrial development. Initially, the funds were directly allocated, with little evaluation of their effectiveness. For instance, we reduced a previous allocation of 40 million yuan to 20 million yuan.”

Narrator: For existing projects, the finance department compiled a policy cleanup list: 25 policies were abolished, 35 reduced, 40 continued, 43 integrated/combined, and 42 strengthened. In one year, 8.58 billion yuan in spending was reduced.

Gu Jianfeng, Director-General, Anhui Provincial Finance Department: Our zero-based budgeting reform is not just about splitting one yuan into two and saving money; it’s about making every yuan work ten times harder, increasing efficiency.

The Origin of Anhui’s Reform: Addressing Imbalances in Revenue and Expenditure, Seeking Impetus from Reform

Narrator:

What is reform? This is a fundamental question. Why has Anhui chosen to tackle the thorny issue of zero-based budgeting reform? The answer can be summarized like this: Reform is about adjusting production relations. Where does the push for reform start? Experience tells us that reform always begins with identifying problems. The reform aims to address the most pressing issues, using constant adjustments in production relations to liberate and develop productive forces.

Anhui’s zero-based budgeting reform is strongly problem-oriented. Its stocktaking was essentially about identifying issues in the budget. From a reform perspective, the exposure of so many issues at once is a good thing. It allows the focus of the reform to become clearer and more precise.

The resistance they encountered when trying to break away from the traditional “baseline budgeting” mainly came from entrenched ideas and interests. The reformers have anchored their crucial goal by breaking away from the baseline, concentrating fiscal resources to accomplish significant tasks, and directing fiscal funds precisely to weak points and critical areas of economic and social development. The zero-based budgeting reform vividly illustrates the reform's difficulty, urgency, and importance.

Here are some of my thoughts

Why is the State Broadcaster Reporting This with the Ministry of Finance’s Support?

This particular “zero-based budgeting” reform was highlighted in the Resolution of the Third Plenary Session of the 20th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in July, and Anhui Province is now implementing it. The leadership views its implementation as bold and effective, positioning Anhui as a model that should be promoted and celebrated.

Local Governments Are Running Short of Money

While the narrator alludes to abstract “production relations” in the last few paragraphs, the report’s subheading gets to the heart of the matter: “The Origin of Anhui’s Reform: Addressing Imbalances in Revenue and Expenditure, Seeking Impetus from Reform.” In plain terms, the government is facing a shortfall, and spending cuts are necessary to balance the budget. The solution? A reform based on the concept of zero-based budgeting.

Significant Fiscal Cuts Are Happening

As the report shows, Anhui alone has seen an 8.58 billion yuan reduction in spending, attributed to zero-based budgeting. The largest cuts have come from areas like industrial development support.

By the way, Anhui ranks as China’s 10th-largest provincial economy among its 31 jurisdictions. Since local governments, including provincial and lower levels, account for 85% of China’s fiscal spending, many Chinese economists—whom I’ve covered—argue that the central government must increase its spending to compensate for the widespread tightening occurring across the board.

Inefficient Spending and Departmental Silos

In Anhui, officials were “stunned” by the sheer number of policies contributing to provincial-level spending, including industrial subsidies, which were “beyond imagination,” in a “shocking discovery.” The report also revealed that businesses have been exploiting government subsidies, confirming inefficiencies in the system.

Contrary to popular belief in the West, coordination between Chinese government departments is not seamless, even under a unitary political system. Department A often doesn’t know or care what Department B is doing. One particularly revealing quote illustrates this: In the “construction of beautiful villages,” the transportation department may build a road in the west, while the water conservancy department digs a canal in the east, the forestry department plants trees in the south, and the housing and urban development department builds urban infrastructure in the north.

Departmental Interests as Barriers to Reform

Departmental interests present significant obstacles to reform, and China’s unitary political system doesn’t necessarily smooth the process. As the provincial official admitted, the reform was “immediately stalled” after the provincial government completed its stocktaking. Only after the provincial leadership convened all the departmental heads did the reform begin to take shape. Euphemisms like problems in “mindset” or “thinking” can’t hide the simple reality: no department wants its budget cut.

The Illusion of Quick Implementation in China

Many in the West assume that decisions made in Beijing are swiftly and comprehensively implemented across the country, due to its unitary political system. However, China knows that this perception doesn’t align with reality, although it doesn’t like admitting it publicly. This is perhaps why the report concludes with a telling line: “The zero-based budgeting reform vividly illustrates the reform’s difficulty, urgency, and importance.”

A Broader Perspective on whether China is an “outlier”

After the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded “for studies of how institutions are formed and affect prosperity,” there’s been an interesting debate on China. Is it an outlier to the “inclusive, non-extractive” institutional framework, which the laureates found crucial for prosperity?

Johns Hopkins Professor Yuen Yuen Ang doesn’t think so. As she noted on Twitter,

China is more similar to *actual* (vs mythological) Western development than most people think.

Yet it is repeatedly cited as an outlier. Why? Because it is a deeply embedded stereotype that West is normal, while non-western cases are weird, deviant, abnormal.

Both Global North & South, including China, reinforce this view.

This is colonial thinking at its most powerful: everyone participates, knowingly or unknowingly.

Now, return to the report on zero-based budgeting in Anhui. I’m perhaps stretching this too far, but return to the report and no, there is nothing new under the sun. That government spending needs to be cut when it runs out of money? That government doesn’t really have a clear picture of its spending, including its industrial subsidies? That for-profit businesses would exploit loopholes to milk government subsidies? That government departments don’t talk to each other? That when it comes to spending cuts, no government department will volunteer?