A global green industrialisation initiative can have a ‘win-win-win’ outcome: Henry Huiyao Wang & Wang Zhi

Opinion: China’s green manufacturing capacity could be aligned with the West’s technological and capital strengths and the Global South’s development needs

Below is the latest opinion column of Henry Huiyao Wang in the South China Morning Post.

A global green industrialisation initiative can have a ‘win-win-win’ outcome

China’s green manufacturing capacity could be aligned with the West’s technological and capital strengths and the Global South’s development needs

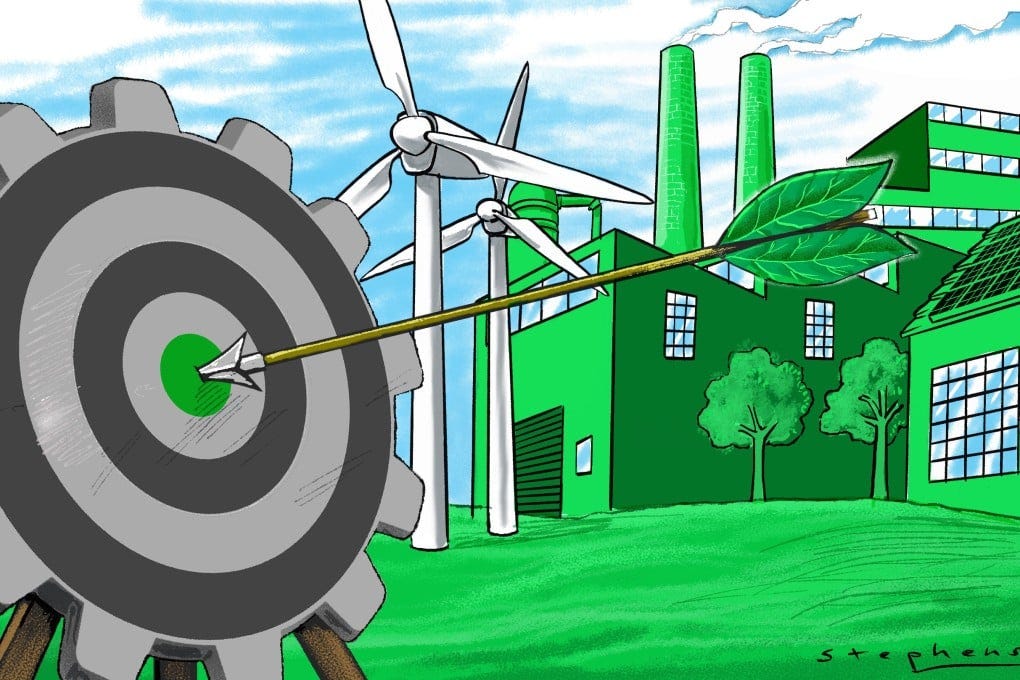

The world stands at a crossroads, amid an accelerating climate crisis, geopolitical tensions reshaping global trade and the demand from Global South nations to exercise their right to industrialise without repeating the polluting mistakes of the past.

A new consensus is urgently needed that moves beyond zero-sum competition and towards collaborative solutions. The path to decarbonisation creates a trilemma of competing interests that threatens progress for all.

First, Western anxieties must be addressed. Some Western governments still believe in the green transition. However, others fear job losses in traditional industries and a decline in international competitiveness. Western countries need a transition that can secure their industrial base and retain jobs that many depend on.

Second is the Global South’s dilemma. These nations have a right to develop. However, many are trapped between a path reliant on fossil fuels that leads to climate vulnerability and a green path that often seems financially and technologically out of reach. They face prohibitive borrowing costs and lack access to financing.

Finally, there is China, which has gone through its painful “pollute first, clean up later” phase. Fortunately, Beijing now produces over 80 per cent of the world’s solar panels and around 60 per cent of wind power turbines. Its progress has reduced the costs of solar and wind power, making renewables more affordable worldwide. China can now help Global South nations build clean, modern industrial systems.

We propose a “Global Green Industrialisation Initiative” to align China’s unparalleled green manufacturing capacity with the technological and capital strengths of the West and the vast development needs of the Global South.

The core of this plan is already in motion. According to the think tank Ember, African markets imported 15,032 megawatts of solar panels from China in the 12 months up to June, a 60 per cent year-on-year increase. Once installed, these imports could add over 5 per cent to total power output in 16 nations. Sierra Leone could generate 61 per cent of its power output in 2023. In Nigeria, the savings from avoiding diesel could recoup the cost of the solar panels in six months. To scale this up, policymakers should consider a multipronged approach.

A Chinese “market-for-technology” deal with the West would be preferable to a zero-sum trade war over green tech. Imagine a strategic bargain where Chinese firms invest in manufacturing plants in the United States and Europe, creating jobs and strengthening supply chains.

In this model, Western partners gain access to advanced, cost-competitive Chinese green technology through joint ventures, accelerating their decarbonisation goals while sharing risks and benefits. This is a pragmatic alternative to protectionism, offering a pathway to securing supply chains and meeting climate targets.

Simultaneously, we must unlock capital for the Global South by treating countries as partners instead of aid recipients. We can break the innovation bottleneck through a three-pillar model.

The first pillar involves capital flow. Chinese banks can provide renminbi loans to domestic creditworthy green enterprises, including joint ventures, which then make direct investments in Global South projects. Data suggests that the credit risk of large Chinese green enterprises is quite low. Moreover, renminbi loans are cheaper than borrowing in US dollars and also help Global South countries avoid sovereign default risks.

Secondly, there’s localisation. Chinese banks can establish branches in Global South countries, absorbing local deposits to serve both Chinese and local businesses, fostering deeper financial integration and building local financial capacity.

The third pillar, multilateralism, incorporates green finance incentives into trade agreements to mobilise funds from the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, New Development Bank and Green Climate Fund that can supply the long-term capital required by large-scale infrastructure.

The goal is to help the Global South cultivate green industries by building ecosystems, not just exporting products. This requires moving to a model that transfers knowledge and builds capacity.

Joint ventures could serve as pioneers. Research from Tsinghua University’s Institute of Global Development shows that there were 95 electric vehicle joint ventures in China from Europe, Japan, the US and South Korea at the end of 2023, contributing 43 per cent of China’s EV production capacity. However, joint ventures face fierce competition in the Chinese market, resulting in overcapacity.

Japanese joint venture capacity utilisation is estimated to be only around 45 per cent, and Korean joint ventures below 20 per cent. This creates an incentive for them to leverage their unique position – with one foot in China’s supply chain and another in global brand networks – to explore other overseas markets, a “win-win-win” situation for everyone involved.

Industrial estates should be established in countries where joint ventures and large firms can form the backbone of a resilient industrial ecosystem, attracting a cluster of smaller businesses too.

Global standards can be set, while solutions are tailored for individual nations. This approach would integrate proven Chinese experience into the global standards system, ensuring interoperability. However, this is not a Chinese-led order, but a collaborative one. It will create a truly mutually beneficial paradigm for South-South and North-South cooperation.

For the West, it means building resilient supply chains and meeting climate goals. For the Global South, it offers a viable pathway out of the fossil fuel trap towards energy self-sufficiency, industrial development and job creation. For China, it represents the next phase of opening-up, transforming its successful domestic green transition into a platform for inclusive global cooperation.

The Global Green Industrialisation Initiative offers an economically sound and politically viable way forward.

Wang Huiyao is the founder of the Centre for China and Globalisation, a Beijing-based non-governmental think tank.

Zhi Wang is a research professor and distinguished senior fellow at the Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University, and a visiting professor at Tsinghua University.

This initiative compellingly articulates how China's green manufacturing dominance, producing over 80% of global solar panels and 60% of wind turbines, positions it as the indispensable catalyst for a needs-based global order that transcends the extractive paradigms of previous industrial revolutions. By framing development through the lens of fundamental human needs (energy access, economic security, climate stability) rather than geopolitical competition, they reveal how China's "market-for-technology" exchanges and renminbi-denominated financing mechanisms can dissolve the artificial scarcity that has trapped Global South nations between fossil fuel dependence and unaffordable green transitions. This approach fundamentally reorients global cooperation around material problem-solving: Sierra Leone potentially generating 61% of its power from Chinese solar imports, Nigerian businesses recouping solar investments in six months through diesel savings. These are concrete demonstrations of how meeting basic energy needs creates the foundation for dignified development without repeating the carbon-intensive mistakes that now threaten planetary stability.

What makes this vision particularly transformative is its recognition that a needs-based order requires structural financial innovation, not just technology transfer. The three-pillar model (direct renminbi loans to creditworthy green enterprises, localized banking infrastructure absorbing domestic deposits, and multilateral green finance integration) addresses the root cause of development inequality: the punishing cost of capital that has historically extracted wealth from the Global South while financing Northern industrialization. By leveraging joint ventures with 43% of China's EV production capacity now underutilized, and establishing industrial estates that build complete ecosystems rather than dependency relationships, this initiative creates a genuinely cooperative architecture where Western technological expertise, Chinese manufacturing scale, and Global South development imperatives align around shared survival. This is not charity or hegemony, but pragmatic recognition that climate stability, energy security, and economic dignity are indivisible global public goods that require collaborative institutional frameworks designed explicitly to meet universal human needs.

I take issue with the idea of an 'accelerating climate crisis'.

An engine is cooled by transferring energy from water to air. The warmed air is displaced upwards. As it rises its density falls away. That rising air cools via decompression and radiation. It loses the energy it gained from the cars radiator before it reaches an elevation of 10 km, a distance that be walked in an hour and twenty minutes. At that elevation 90% of the bulk of the atmosphere is beneath. The atmosphere is not a sink for energy. Never was and never will be. It very efficiently vents energy.

The land does not absorb energy to depth and by and large it loses that energy overnight.

The ocean is a sink for energy. It is where the air tends to descend in high pressure cells that are variably extensive and largely cloud free because the air is compressed as it descends, becomes warmer and its relative humidity falls away. The prime source of ascending air to feed the mid latitude high pressure cells over the oceans can be found in the near polar regions in winter where the partial pressure of ozone increases and especially so as the sun sinks to the horizon or disappears below it so that the quotient of ozone busting UV radiation is diminished. Ozone busting oxides of nitrogen descend from the mesosphere greatly influenced by waxing and waning solar phenomena. It’s the so called ‘polar cyclones’ associated with the presence of ozone at the elevation of the upper troposphere and the jet stream that drive the high latitude ascent that feeds into the mid latitude descent driving change in cloud cover over the oceans. In this manner the Earths energy budget is altered. The influences of man and the energy absorbing and warming influence of carbon dioxide and water vapour are insignificant and minor players, if players they be at all, in the grand scheme of things.