Between Trust and Tension: Wang Jisi Reflects on U.S.-China Relations

With the Penn Project on the Future of U.S.-China Relations, China's leading America watcher shares personal stories, assesses growing strategic rivalry, & explains why dialogue matters more than ever

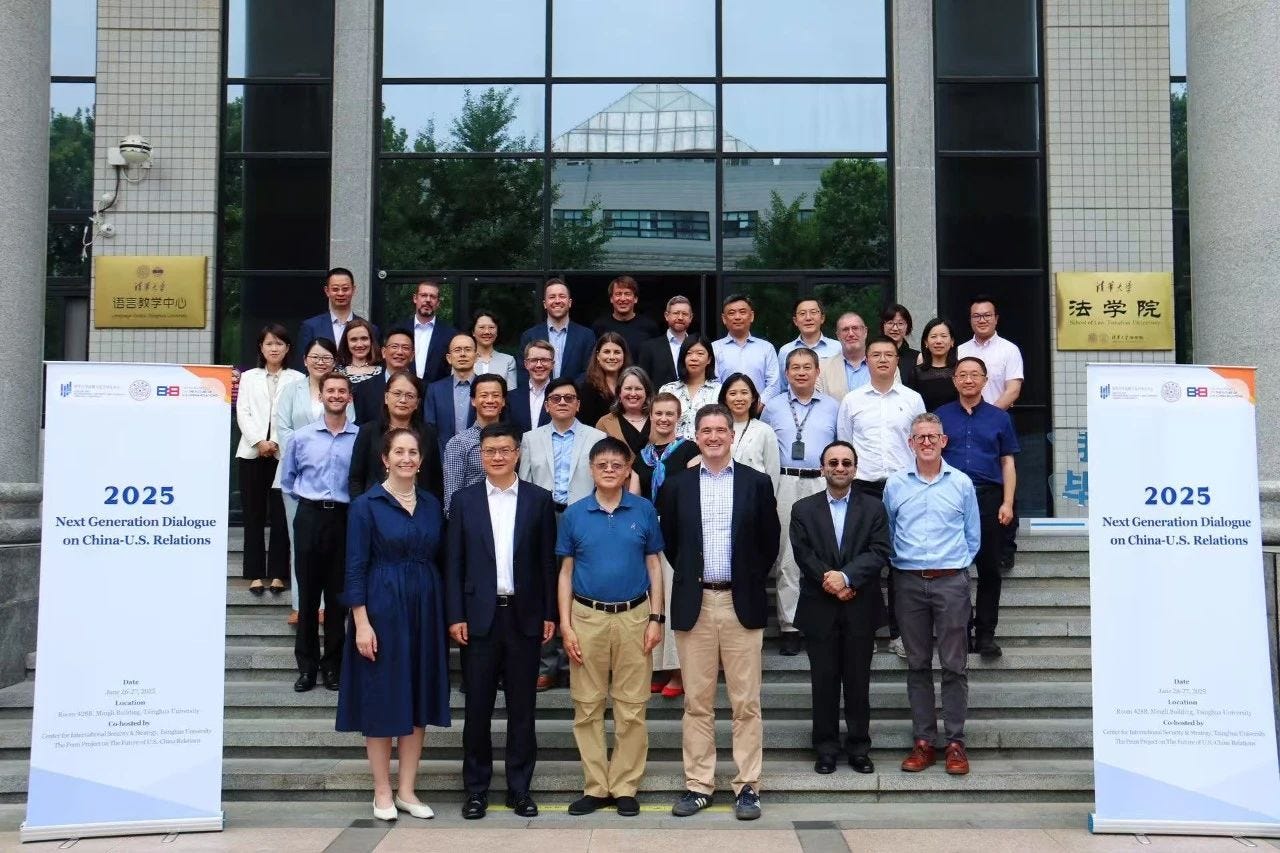

On June 26–27, 2025, the Center for International Security and Strategy (CISS) at Tsinghua University and the Penn Project on the Future of U.S.-China Relations at the University of Pennsylvania held the “U.S.-China Next-Generation Scholars Forum” in Beijing.

At noon on June 26, during the forum, Professor Wang Jisi, Academic Committee Member of CISS and Boya Chair Professor Emeritus at Peking University, was invited to deliver a luncheon speech. In his remarks, Wang shared his decades-long experiences, personal stories, and reflections on U.S.-China people-to-people exchanges and also responded to questions raised by participating scholars.

Against the backdrop of ongoing challenges facing U.S.-China cultural and academic exchanges. With Wang’s consent, CISS has translated and compiled portions of his English-language luncheon speech and the subsequent Q&A session into Chinese on August 6.

The following newsletter is based on an English-language transcript provided by Da Wei, Director of CISS. Wang personally reviewed and edited it before publication.

Neysun Mahboubi, Director of the Penn Project on the Future of U.S.-China Relations, also consented to publication.

Professor Wang has always been my mentor, teacher, and colleague. He has helped me personally, and I believe he has also supported many other Chinese scholars here. I should also mention that Professor Wang serves on the academic committee of our center, which is a great honor for us.

When I reached out to Professor Wang to ask if he could speak at this workshop, to be honest, I wasn’t sure he would have the time—he is extremely busy nowadays. But to my surprise, he replied to my message within a minute and immediately said yes.

What I admire about Professor Wang is not only his deep knowledge, but also his character, his attitude, and especially his passion for promoting dialogue and exchange between China and the United States. I think one reason he agreed so quickly to join us today is because this is a next-generation dialogue. And truly, I believe there is no one in China better suited than Professor Wang to speak on this topic.

As for what Professor Wang is going to share, he told me he would talk about his personal experiences in China–US exchanges over the past several decades—more than 40 years, I think.

So now, the floor is yours, Professor Wang. And after his talk, we will have a Q&A session.

Thank you very much, Da Wei. Your introduction makes me feel even older than I actually am! I wish I were of the same generation as you are.

To be honest, I haven’t prepared a formal speech today. I don’t have a written script, and I’m not entirely sure what I will say. But perhaps I can share a few reflections on my experiences with Americans.

Recently, there was a new publication entitled Chinese Encounters with America, and the person who contributed an essay about me was actually my old friend and mentor Mike Lampton, professor emeritus at SAIS, Johns Hopkins University. I met him two days ago in Beijing; he came with his family, including his two grandchildren for vacation.

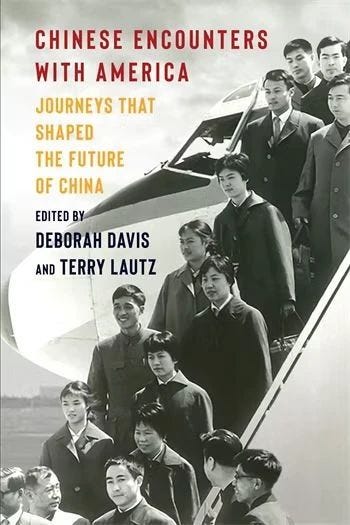

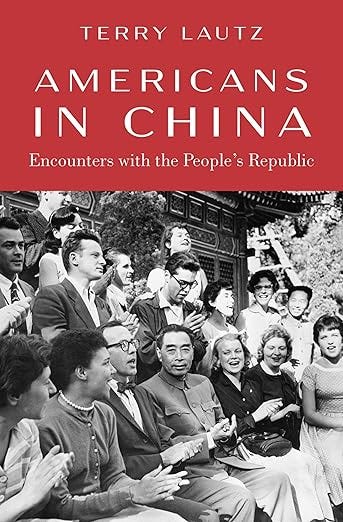

I have brought a copy of this book with me, and highly recommend it to you. One of the editors is Terry Lautz, an old China hand – and a good friend of mine - who worked for the Henry Luce Foundation for decades. He also edited a volume entitled “Americas in China: Encounters with the People's Republic.” These two books are a pair, presenting biographies of about 20 Americans and Chinese of different occupations and with different backgrounds. They describe these individuals’ experiences in, and contributions to, the history of China-US relations and are very worth reading.

One of the questions people often ask me is: How do I judge Americans, especially regarding their attitudes toward China? Politically, some Americans can be described as “pro-China,” while others are “anti-China.” This is a popular understanding in China. The conventional view in China is that we should get closer to the pro-China Americans and keep some distance from the anti-China ones.

But personally, I don’t really see it that way. I know some Americans who are not exactly friendly toward China—or, more accurately, not friendly toward the Chinese government or the Communist Party. They sometimes declare “I’m not an ideologue,” or “I’m not an ultra-nationalist” to defend themselves. That’s okay to me, because I judge other people not by their political ideas but by their honesty and sincerity.

I hope that my colleagues and counterparts will hold a similar attitude toward Chinese scholars. I actually hope more people, even those who are critical of China, could get to know ordinary Chinese people better. If some of them still prefer to keep distance from me, honestly, I don’t mind.

In my career of studying the United States and US-China relations, I have noticed the huge gap between how American and Chinese define their identities. This difference roots deeply in their societies and social values. Many years ago, I visited the Lyndon Johnson presidential library in Texas, and found this quotation of Johnson: “Throughout my entire public career I have followed the personal philosophy that I am a free man, an American, a public servant, and a member of my party, in that order always and only.” As a politician, President Johnson might not have followed the philosophy he declared truthfully. However, the statement itself is meaningful: Americans value freedom or liberty above other things, and this is proved by public opinion polls.

As a student of US affairs, I truly respect American identity. But in China, things are very different. If I had to describe my own identity publicly, I should probably say: I am first and foremost a Community Party member, and second, I am a cadre (or professor, or whatever occupation I belong to), and third, I am a Chinese citizen. Finally, I would never, and should never, become a “free man.” Although the Chinese also treasure individual freedom in their daily life, in history and in present days, that is not to be announced openly. Collectivism, not individualism, is a popular social value in China.

Despite this difference, Chinese and Americans can get along with each other very well personally. We know each other. We understand each other based on both our differences and our similarities. At the end of the day, we are all human beings. We are citizens of our own country, loyal to our nations—but we should also be able to tolerate each other’s political ideas. That is what I try to practice in my career as a US watcher.

Of course, sometimes I have disagreements, even conflicts, with some American colleagues. We are in different positions in our own society, and it is not easy to understand each other’s personal choices. Let me share one story with you. Back in 1990, I was invited by my mentor, Mike Oksenberg, to teach at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor as a visiting scholar.

It was not long after the 1989 Tiananmen incident, and many Chinese scholars in the U.S. chose not to return to China. I decided to bring my wife and my 10-year-old son with me to Michigan and had never thought of doing a PhD or stay longer after the stint.

A few months after my arrival at Ann Arbor, Mike Oksenberg visited China and heard from my colleagues that “Wang Jisi probably won’t come back because he had sold his TV set before leaving.” The fact I had brought my family with me reinforced that suspicion. When he returned to the U.S., he asked me directly, “What is your plan? Are you really coming back to China?” I felt a bit insulted by this question. After all, Mike had planned to raise funding and make arrangements for me to teach a course for the fall semester in 1990, and I agreed. Now it seemed that he was testing me.

I told Mike frankly: “If you don’t trust me—if you don’t think I’m a serious scholar and keep my promise—I can go back to China, or travel elsewhere to complete my program.” The next day, I spoke to his good friend, Ken Lieberthal, and told him that I was unhappy about this lack of trust. Ken understood, and I thought he was going to tell Mike what I said.

That was a Friday afternoon. I had a very unhappy weekend reflecting on this. On Monday, Mike invited me to lunch. Usually, we would split the bill for a simple meal, but this time he insisted on paying. He told me he respected me and my decision. Later that day, he even invited my wife and son to go swimming, and we resolved our misunderstanding.

I realized he had been worried that I might want to stay in the U.S. permanently, trying to get a PhD or find a job. In that case, it would have made him embarrassed in front of his colleagues in America and China. But after that, I taught a wonderful course on Chinese foreign policy at Ann Arbor in Spring 1991 that made Mike very proud. We became very close friends. He later told his students: “I respect Wang Jisi because we are both nationalists—we love our own country deeply.” That is a friendship I will always remember.

In early 2001, I learned by Mike’s email that he had an advanced cancer. I took a side trip from Washington, D.C. to see him at Stanford University. He held a lunch seminar on my behalf. When we said goodbye that afternoon, both of us shed tears because we knew it would be our last meeting.

Over the years, I’ve had many friendships like this with American scholars, including people like Joseph Nye and Henry Kissinger, as well as younger scholars. But it is also true that I never got to know many ordinary Americans—lower-income workers, farmers, taxi drivers. That is my limitation, and because of it, I’ve made mistakes in understanding American society and politics. I am still learning, and I hope to keep learning through conversations with people like you.

These are just my personal reflections. Thank you very much, and I’m happy to answer any questions you might have.

Da Wei:

Okay, thank you very much, Professor Wang, for sharing those very touching stories about your experiences with Americans—from a young age and across so many different professions. It was really wonderful to hear.

Now, I’d like to open the floor for questions and comments. I saw that Neysun Mahboubi was the first to raise his hand, so please go ahead.

Professor Wang, thank you so much for joining us today—it’s truly an honor. I hadn’t had the chance to meet you until just about 20 minutes ago, so I’m especially delighted that you’re attending this workshop.

This workshop is actually the third—or in some ways, even the fourth—that Professor Da Wei and I have organized at Tsinghua University in under two years. We’ve been trying our best to bring together American and Chinese scholars for meaningful, in-depth academic dialogue, which, as we all know, became so much harder during the pandemic.

In fact, during the pandemic, the only people I know who really kept up people-to-people exchanges were you and Scott Kennedy. I’m very curious: what motivated you to keep pushing so hard at that time—when it was so difficult to travel—to go to Washington yourself and also to bring Scott here to China?

Because while our work has certainly had its challenges, I think what you and Scott managed to do at the height of the pandemic was even more difficult. I’d love to hear your thoughts on what drove you to keep those exchanges alive during that period.

Wang Jisi:

Thank you. Scott Kennedy and I developed a personal friendship—although not over as many years as with people like Ken Lieberthal or Mike Lampton.—but still a very good relationship. Scott suggested that we should meet in person, and I agreed to travel to the United States to join him as the first step.

At that time, one major obstacle was that travel was very expensive, and it still is today. Fortunately, I had good friends in China who had the means and were willing to support this effort, for which I am very grateful. So I went to see Scott and other American colleagues.

My thinking then was simple: I hadn’t been to the United States for a couple of years, and I really missed those days there, and my friends. I felt that if I wanted to keep calling myself a “U.S. specialist,” I had to go in person—to hear what people were really thinking. Since then, I’ve tried to visit the U.S. regularly, about every six months. I also serve on the international advisory board of an insurance company headed by Evan Greenberg, which gives me another reason to stay connected.

I’ve always believed that if I stayed in China for more than half a year without visiting the U.S., I wouldn’t really understand the country anymore. Only by talking face-to-face with Americans can I get a true sense of U.S. politics and foreign policy. That was my determination, even though there were many difficulties.

For example, on that trip, I traveled with a younger assistant. At the JFK airport, I was taken to the border security hall where I had to wait for about five hours. The security officer said politely, “We know who you are, but who are you going to meet in Washington D.C.?” I explained, but they didn’t seem very interested in the details. Then he asked, “Are you also going to New York City?” I said yes. “Who are you going to meet in New York?” I thought to myself that maybe I should mention a big name. So I mentioned Henry Kissinger’s name. He seemed perplexed. Obviously, he didn’t know who Kissinger was.

At one point, I said to him, “You have your job, and I have mine. I understand why you are doing it, but this waiting time is really far too long.” For the first two hours, I just waited. Then he interviewed me politely and said he still had to wait for a phone call from his boss, so I had to wait another two hours. When he came back, he told me, “My boss asked me to check one more thing. According to our record, many years ago you had conversations with China’s top leader.” Do you have any contact with the current leadership?”

I told him honestly, “The current leaders are much younger than me now, and I don’t have a personal relationship with them.” Which was true.

Eventually, they let me go. At the end, I said I would tell the US State Department my experience with the border security. The officer willingly showed me his name tag. I noticed it didn’t look like a typical American name and said that to him. He smiled and told me he was an immigrant from Afghanistan. I was not very much annoyed by this encounter as I didn’t take it personally. I understood that they were just doing their job, and I was doing mine. He didn’t ask me any questions that were politically sensitive, and he was not rude.

To me, this wasn’t about personal feelings—it was a reflection of the broader deterioration of U.S.–China relations, which I have to face as part of my work. My mission has always been to keep contacts alive with American colleagues. Even experiences like that didn’t scare me away from doing what I believe is important.

Da Wei:

Thank you. I think what you experienced really shows the gap between generations. For people like Xiao Tao, Xiaoyi Jin, and myself, our experiences at immigration are usually much shorter—maybe just three or four hours at most, definitely less than yours!

Okay, let’s continue. I see that next we have Joshua, then Ali, and then Carl—in that order. Please go ahead.

Thank you very much for your remarks, Professor Wang. I wanted to ask you about the question of hegemonic transition. This topic actually came up during a recent discussion we had at the U.S. Embassy. As we know, historically, most transitions involving rising powers have not ended peacefully. There are exceptions, of course, such as when the United States overtook Britain in the early 20th century, but that was a moment when the two countries’ political systems were arguably more similar.

Looking ahead, there might still be possibilities for what we could call hegemonic renewal by the United States, but it seems more likely that we’re entering a period of bipolarity.

I’m curious to hear your thoughts on how you see this hegemonic transition unfolding. More specifically, how do you think we, as individuals, can use whatever agency we have to influence our respective governments to help ensure that this transition, however it ultimately plays out, doesn’t end in great power conflict or war?

Wang Jisi:

My honest answer is: I don’t know. There simply aren’t many historical examples we can use for direct comparison. The only somewhat similar case of competition between two major powers with very different ideologies was the Soviet–American Cold War.

That Cold War ended with the collapse of the Soviet Union—not only the fall of the Communist Party itself, but also the disintegration of the entire country. After all, the Soviet Union was a union of what they called “socialist republics,” which in reality were not truly republics.

So, when I think about the possible “end game” of this current strategic competition between the U.S. and China, my personal feeling—truly from the heart—is that I might not live long enough to see it. The previous Cold War lasted 43 years. From the end of that Cold War until now, it’s been only about 30-something years. If this new Cold War were to last 43 years as the last one, I would be in my late eighties. And even then, it might still not be the real end of the U.S.–China rivalry.

One possible outcome of this rivalry could be some form of mutual compromise: we remain two major powers, the competition continues, but we avoid war, especially a hot war or nuclear war. That could be the best-case scenario.

Another, more worrying possibility would be the collapse of one country or the other. For example, an unlikely scenario where the United States disintegrates—California and New York become independent—or China breaks apart as a nation. But honestly, I don’t think that’s realistic.

So in terms of power transition or hegemonic change between the United States and China, I don’t expect either country to completely collapse. But it is possible for either or both to be weakened. What happens then? I don’t really know.

Some people argue that the United States is already weakening because of its domestic politics. Personally, that saddens me. I’ve asked some Chinese officials that if the U.S. is truly declining—its economy slowing, its currency weakening -- what does China really gain from that? After all, China’s economy is deeply intertwined with the global economy, in which the United States still plays a central role. So, from my own perspective, I don’t want to see the U.S. economy in decline.

But I know this view isn’t widely shared in China. Many people, including some of my friends, believe the U.S. is simply a “bad” or even “horrible” country. In fact, just recently, a friend from Boston College told me that, in his view, most people in China think the U.S. is truly horrible. And sometimes, I’m criticized by people who say: “Even a primary school student in China knows the U.S. is bad. Why doesn’t Wang Jisi see that?”

This is part of what we’re facing now: a deep erosion of mutual trust, which will likely persist for many years. Over ten years ago, I co-authored a study with Ken Lieberthal, whose title I almost forget now, about “mutual distrust” between the United States and China. Since then, things have only deteriorated more rapidly.

Can we reverse this trend? Honestly, I don’t think so. We will have to live with this reality: the U.S.–China relationship may get worse before it gets better, and it’s very uncertain what the “final outcome” will be.

So, to sum up: my simple answer remains: I don’t know. Because ultimately, the relationship depends not only on what happens in bilateral diplomacy, but also on how we manage things domestically in China, and how Americans manage things domestically in the U.S. Frankly, I am more worried about U.S. domestic politics right now than about China’s domestic situation.

Thank you so much, Professor Wang. Maybe I’ll just speak without the microphone. It’s truly an honor to meet you, and thank you for spending your afternoon with us.

I have to say, I was expecting—and I would have also enjoyed—a more traditional presentation from you about the structural forces shaping U.S.–China relations and the big picture of geopolitics. But what I really appreciated today is that you encouraged all of us to think about the human implications of strategic competition. I also found the personal anecdotes you shared to be very powerful reminders that, while we often talk about geopolitics in abstract terms, these dynamics ultimately affect real people’s lives—in the United States, in China, and around the world.

On that note, I wanted to ask you a kind of hypothetical question. You mentioned that there are many misperceptions on both sides—misunderstandings about each other’s societies and economies. If you were giving this same talk, but instead of speaking to scholars in this next-generation dialogue, you were speaking to a group of American high school students and a group of Chinese high school students, what would you tell them?

Specifically, what do you think are the biggest misperceptions that ordinary Americans have about China’s economy and society? And what are the biggest misperceptions that young Chinese might have about America’s economy and society? If you were addressing them directly, what message would you want to share?

Wang Jisi:

There are many things I’ve been thinking about. One topic I actually hesitated to raise is religion and civilization. How many people in China truly understand that most Americans hold religious beliefs? Many believe in Christianity; some practice Islam; others follow different faiths. This sense of religious responsibility and worldview often shapes how Americans see issues like human rights in China, Tibet, or Xinjiang. Their views come not only from political beliefs but also from deeply rooted religious convictions, and we need to understand that.

By contrast, most Chinese people do not have religious beliefs in the same sense. When I once discussed this with a Chinese official in charge of religious affairs, he told me that in fact many Chinese do hold religious beliefs. They might attend family churches, go to Buddhist temples, or follow other traditions. Buddhism, for instance, is quite popular. Still, in general, religion does not play as central a role in Chinese society as it does in the United States. And because of that, it’s often hard for us to fully understand why Americans see China the way they do.

On the American side, there are also misperceptions. I remember a personal story from many years ago: an American professor was visiting Beijing and went to Tiananmen Square. There, he saw Chinese children—the Young Pioneers—taking an oath: “为了共产主义事业,时刻准备着” (“Always be ready to fight for communism”). The professor was struck by this and thought: “These young children are openly pledging themselves to communism, which opposes capitalism. So, when they grow up, won’t they naturally see us as enemies?”

How should we answer that? It is true, in a formal sense, that members of the Communist Party uphold the ultimate goal of transcending capitalism or imperialism. But in practice, many people don’t take these slogans literally in their daily lives. Yet it is hard to explain that nuance to outsiders, because what is written and what is actually believed can be different. Americans often ask: What is really true? What do Chinese people truly believe in? And even within China, there are debates about whether Chinese people genuinely share a common belief system, and if so, what is it?

At the same time, I have my own questions about the American belief system today. For example, does Donald Trump share the same fundamental values as most Americans in this room do? I really don’t know. And the more I study the United States today, the more confused I become.

So, on both sides, there are deep uncertainties, not just about policy, but about what people genuinely believe in. And that is what makes understanding each other so challenging.

Thank you very much, Professor Wang, for taking the time to speak with us today. My question is actually less about China’s relationship with the United States, and more about China’s relationship with the rest of the world. Earlier, Professor Da Wei made some comments suggesting that in the last five months or so, it seems that Beijing may be losing faith in globalization, or at least in the idea that China should deeply engage with the broader international system. Instead, there appears to be a search for what China’s role in the world might look like as relations with the United States grow more complicated.

So, first, I’d like to ask: do you agree with Professor Da Wei’s assessment?

Second, if that’s indeed the case, there seem to be two historical models China could follow. One would be similar to the Ming dynasty model: self-reliance, turning inward, and limiting external engagement. The other would be closer to the Tang dynasty model: remaining open to the world, encouraging exchanges and flows—not necessarily centered on the United States, but deepening ties with regions like Africa, Southeast Asia, or elsewhere.

So my question is: between a “Ming dynasty” path of closing off, and a “Tang dynasty” path of broader but non-U.S.-centered globalization, which direction do you think China is more likely to pursue?

Wang Jisi:

That’s a very thoughtful question. Honestly, I haven’t thought deeply about it in those historical terms, because I don’t study Chinese history that seriously—especially not the Tang or Song dynasties. And in the end, all dynasties collapsed one way or another. So I’m personally not very comfortable making that kind of comparison.

Still, sometimes I do reflect on it, although it feels a bit politically sensitive to say so. After all, every dynasty had its rise and fall. Even the shortest one, like the Yuan dynasty, lasted over a hundred years. Our current system has been around for seventy or eighty years, and it could very well last many more decades or even centuries. But again, I don’t really like framing the present in those historical dynastic terms.

As for your broader point: yes, I firmly believe that China must engage with the entire world. You asked specifically about relationships beyond the United States, and I take that seriously. I’ve tried not to only focus on visiting the US. Just last month, for example, I traveled to Hungary, Romania, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia. I found it fascinating: their lifestyles are quite distinct—not quite like Western Europeans, but also not like Americans. And yet, these societies value economic growth, innovation, and trying new ideas.

In that sense, I think China also needs to embrace new things and openness. Personally, because of my age, I sometimes feel resistant to change, but I know we must adapt. Not everything new is automatically good, but some changes are necessary, and that’s part of living in a modern world.

So overall, I don’t support the idea that China should turn completely inward or try to be fully self-reliant. We need trade, exchanges, and compromises, not just with the United States, but with many other parts of the world -- the Global South, our neighbors, and others.

In short, I think China’s destiny can’t be defined just by its relationship with the U.S. alone. We must look beyond that to many other countries and find our place and identity within the broader international community.

Thank you very much, Professor Wang. I’m truly touched and impressed by the personal stories and experiences you shared about your academic exchanges with the United States.

My question is about your observations regarding college students here in China today—their perceptions and attitudes toward academic exchanges, not only with the U.S. (where, as we know, the barriers have become quite high), but also more broadly.

I’ve previously used data from Tsinghua University to illustrate that there has been a drastic decline in the proportion of Tsinghua students pursuing studies abroad. For example, 20 or 30 years ago, more than 50% of some cohorts studied abroad, especially in the United States. Now, as far as I know, that figure has dropped to less than 10%. I imagine the situation at Peking University is quite similar.

Beyond the numbers themselves, I’m curious about your sense of how the current generation of Chinese college students view China’s place in the world. On the one hand, there seems to be growing national confidence and patriotism. On the other hand, young people also face significant challenges such as rising youth unemployment and increasing uncertainty about the future.

Given your experience engaging closely with students and observing these dynamics over time, what is your sense of how today’s Chinese college youth feel about China, about the outside world, and about their own role in it? Thank you.

Wang Jisi:

My personal sense is that many in the younger generation, though certainly not all, haven’t fully come to terms with just how badly U.S.–China relations have evolved, and China’s relationships with the Western world at large have deteriorated in recent years.

When it comes to studying abroad, yes, visa difficulties are one factor. But beyond that, young people today also have to think carefully about their families and long-term prospects. Personally, I’m very family-oriented. For example, my son studied abroad for a while, but now he’s in Beijing. And my grandson is only four years old. I prefer not to send him to an international school in Beijing, not only for practical reasons but also partly for political reasons. I’m simply not confident that U.S.–China relations will return to the “old days,” the days when I could co-author papers with American scholars like Ken Lieberthal and Joe Nye, or have regular exchanges like I did with Scott Kennedy.

From what I see, some younger people at Tsinghua and Peking University haven’t fully realized how serious the situation could become. In my view, it’s almost certain that relations will not go back to what they were before, and they could very likely get even worse. We should be prepared for that.

That’s something I think this generation still needs to reckon with.

Neysun Mahboubi:

Could I ask a brief follow-up? I know we’re short on time, but I think this is really important.

Earlier, you mentioned that as someone who studies the United States, you feel that if you go more than six months without visiting the U.S., you lose touch with what’s really happening there. Many of us who consider ourselves China experts feel exactly the same way about needing to spend time in China to stay grounded.

But what strikes me is that while you yourself feel this strong need to go to the U.S, regularly, it seems that your advice to your students—the next generation of U.S.–China scholars—is actually not to go, or at least to be very cautious about going.

And that makes me worry: Who, then, will be the next generation of true American experts on China? And who will be the next generation of Chinese experts on the United States? For example, I have a student here today, Blake, who is currently the only American exchange student at the Guanghua School of Management, and he’s about to study at the Yenching Academy. That’s just one person.

So my question is: If we both recognize the importance of spending real time in each other’s countries, how can we encourage and sustain that next generation of scholars, both Americans who truly know China, and Chinese who truly know the United States? Because I think this gap could become an even bigger problem in the future.

Wang Jisi:

I have great admiration for the younger generation. But there is a difference between our capabilities and our wishes. I want my students to be very well educated and globally minded. If they ask me personally whether they should go to the United States, I’ll tell them to carefully consider their family, their parents, and their own futures. I advise caution; not that they should never go, but that they should be realistic about the future of U.S.–China relations, which I do not expect to improve significantly anytime soon.

Da Wei:

To add to that, I know that at the international high schools in Beijing, this year’s admissions have hit a record low. The recent Zhongkao results showed that very few ninth graders are applying to international high schools here, which is usually the first step for studying abroad. This is quite alarming news.

Wang Jisi:

On the positive side, people now generally live longer. They can enjoy greater longevity. So even if they delay going to the United States until they are 50 or even 70 years old, they still have time to experience life abroad.

Thank you, Professor Wang, for your truly illuminating and valuable insights.

Speaking of longevity, I believe you have been studying the United States longer than many Americans have even been alive. So I’m curious about your thoughts on Donald Trump. He has obviously played a significant role in U.S.–China relations. Beyond the political impact, I’m also interested in your more personal, impressionistic view based on your experience studying and living in the U.S. Do you see Trump as an anomaly within America, or as a reflection of some broader aspects of American society? How do you perceive him as a person and as a manifestation of certain trends or forces?

Wang Jisi:

I hope to see a US president who will follow America’s political tradition, and that h this period in U.S. history will not be anachronism. But frankly, America today does not like normal—it’s abnormal. I don’t mean this lightly. I can’t say exactly what that means, but it’s definitely an exception, not the normalcy.

I haven’t talked with many Trump supporters, but one person who dislikes Trump told me that Trump has charisma, and I agree. He definitely attracts a great deal of attention and is genuinely popular with many Americans. That’s a reality we have to accept.

Trump himself hasn’t changed; he has been the same person for many years. What has changed is the society—the widening gap between the rich and the poor, the evolving racial dynamics, and the shifting norms around political correctness. These are complex issues that fuel his appeal and our broader political challenges.

Personally, putting aside political biases, I do not like seeing someone playing a leadership role who is not representing the better part of the United States. But I have to face the reality and ask myself: is there something wrong with my judgment, and what goes wrong in American society that drives it toward disunity?

As for whether Trump will run for a third term, he has said he wants to. If he does, he will be struggling for presidency at 82 by 2028. President Trump looks healthy and energetic today. So again, this is a possibility we have to think about.

Thank you so much, Professor Wang, for being with us today and sharing your experiences. It’s truly an honor.

I wanted to follow up on the question you addressed earlier about your outlook on Trump, specifically to ask your perspective on his policies toward Taiwan. I believe you commented on this early in his administration, and I’m curious how your views have evolved regarding the direction of U.S. Taiwan policy, the Taiwan question, and U.S.-China relations more broadly. We’ve already touched on this quite a bit this morning, but I’d also really appreciate any historical perspective you can share based on your experiences—how the Taiwan question has played out in U.S.-China relations in the past and what lessons we might learn as we enter perhaps a more turbulent era.

Wang Jisi:

I wonder what is the depth of Trump’s understanding of Taiwan. A very serious question I’ve heard from some distinguished Chinese colleagues is whether we could strike a deal with Trump on Taiwan. They think maybe we could compromise on trade or other issues, and in exchange the U.S. would give up its support to Taiwan. Can Taiwan really be part of such a tradeoff? I don’t think so. Although Trump is a powerful figure, he still has limits in dealing with China, especially on crucial strategic issues like Taiwan. It’s much easier for Washington to negotiate trade deals or technology transfers than to make concessions on Taiwan.

And frankly, Taiwan’s status isn’t, and shouldn’t be, decided by the United States. Taiwan is legally a Chinese territory. Its international surroundings were shaped by earlier history and complex realities during the Cold War years. I don’t believe its something Trump could simply have a “deal.” Nor do I think he fully understands the complexity of the Taiwan question. It’s a highly sensitive issue that requires much political wisdom to think about.

You mentioned that over the years, you’ve briefed many Chinese leaders about America. Could you share with us what kinds of questions they usually ask about the United States? What do they want to understand most? And are there any particular books, films, or other sources that you’ve recommended to them to help them learn more about America?

Wang Jisi:

I have to be honest: I actually haven’t had that many direct interactions with senior Chinese leaders or high-ranking officials.

Amy Gadsden:

Even in earlier years?

Wang Jisi:

Well, I used to brief President Hu Jintao in a group setting when he was China’s top leader. I remember once he said in early 2008 that he had a good working relationship with President George W. President Bush, and asked us who might become the next U.S. president.

I replied that there was a strong competition between the Republicans and the Democrats. I thought Republicans might have the advantage in terms of campaign strategy, but the Democrats represented the tide of change, and therefore would likely win the national election. Among the Democrat candidates, it would come down to Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama, and I guessed that Hillary Clinton might win the nomination. That turned out to be a wrong prediction. But this was in early 2008, so it wasn’t too far-fetched.

In general, Chinese leaders are very interested in understanding the United States, and they actually know quite a lot. Some of the information they receive is very accurate, but some is less so, like what I just said.

I would emphasize that many Chinese officials today have a broader and deeper knowledge about the United States than some American policymakers have about China.

Da Wei:

Thank you. With that, I think we can conclude this keynote session. Professor Wang has been so generous with his time, sharing his experiences, insights, and wisdom on U.S.-China relations. For me, and I believe for many of you, this is a dialogue we will remember for a very long time. So thank you very much. Please join me in thanking Professor Wang.

Now, it’s time for lunch. But before lunch, we’ll take a group photo. You’re invited to go downstairs. We’ll gather for the photo on the steps outside the building so we can get a nice picture together. After that, we’ll come back for lunch.

With all due respect for the contribution to Sino-American relations by Professor Wang over the years, I need help to clear up my understanding of civilizational identity of Americans and Chinese.

Professor Wang Jisi’s recent reflection on identity is striking. But what is most revealing is not what he says, but what he leaves out. When Lyndon Johnson declared, “I am a free man, an American, a public servant, and a member of my party,” he laid out an American grammar of selfhood: individual freedom first, nation second, profession third, party last. Wang echoes the structure: “I am first a Communist Party member, second a professor, third a citizen, never a ‘free man’.” Both men suppress family, clan, and place, presenting themselves in purely professional-political terms.

Yet in China, everyday language encodes a different grammar of belonging. Meeting a stranger, one asks:

• 你是哪里人? (Nǐ shì nǎlǐ rén?) — “Where are you from?”

• 您贵姓? (Nín guìxìng?) — “What is your honorable surname?”

Identity begins with place and lineage, not job title or political affiliation. Only later comes profession. By contrast, Americans answer “Who are you?” with “I’m a lawyer” or “I’m from New York,” reducing identity to occupation and current residence.

Here lies the deeper problem. Wang’s self-description elevates Party membership above civilizational belonging. Yet only around 100 million Chinese are Party members out of a population of 1.4 billion. To define selfhood by this minority status is to create a class distinction — the very opposite of Communist egalitarianism. The Party calls itself 中国共产党 (Zhōngguó Gòngchǎndǎng) — literally the Chinese Communist Party. “Chinese” comes first, because the Party sees itself as vanguard and guardian of a civilization, not a class apart from it.

That is the heart of the difference. In China, civilization comes first: family, clan, nation. The Party’s legitimacy rests on protecting that continuity and delivering common prosperity. In America, there is no civilizational anchor to protect. The polity is fragmented, polarized, and reduced to competing party loyalties. Johnson’s declaration reflects this: self, nation, profession, party — but never family or civilization.

Thus when Wang defines himself as “Party member first,” he inadvertently reproduces a class identity that runs against the Party’s own founding mission. It is civilization that all Chinese share; the Party is its protector, not its replacement. If scholars continue to speak only through professional and political masks, they distort both China and America — and International Relations as a field will go on manufacturing misunderstanding rather than coexistence.

Very Interesting article, thanks for the information!