Calls to address pension inequality grow

Retired minister and economists urge raising farmers’ pensions amid disparities.

A retired top financial regulator has lent his support to the growing calls for the Chinese government to significantly increase pension payouts for its farmers. In a high-profile national forum, he advised that Beijing should bridge the gap between the pensions of farmers and urban retirees.

Guo Shuqing, former Communist Party secretary of China’s central bank and head of the country’s banking and insurance regulator, told the annual Boao Forum for Asia on Tuesday (March 25) at China’s southernmost island of Hainan that the monthly pension for retired urban workers—at 3,200 yuan ($441)—is now 14 times higher than that of farmers, who receive a meager 240 yuan ($33).

“China should think about narrowing the unreasonable gap in pension payout between different regions and groups, and in particular, between farmers and retired urban workers,” Guo said. “I think (China) should push for a solution as soon as possible. It should consider, within the next 5 or 6 years, to raise the farmers’ pension to the lower end of urban retirees,” he added during a session focused on pensions at the forum.

Zheng Bingwen, a scholar from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, who also appeared at the session, cautioned against excessive expectations. In an interview with the Economic Observer, Zheng, while ostensibly supporting the idea of raising farmers’ pensions, stressed that such pensions in China primarily rely on government spending, and that the Communist Party-led government lacks the fiscal resources to implement a large increase for its poorest citizens.

The enormous gap between the pensions for urban and rural retirees results from their different funding sources, Zheng said. Urban retirees and their employers contribute the overwhelming majority of urban pensions, while 90% of farmers’ pensions are financed through fiscal spending at various levels of the Chinese government.

“The rural pension system is not a traditional pension insurance system. Instead, it is a flat-rate pension subsidy system that largely depends on the financial conditions of local governments,” Zheng said. “Rural people can start receiving benefits at age 60, and everyone is eligible. There are no requirements for contribution records or a minimum number of years of contributions, and there are essentially no other qualification conditions.”

However, supporters point to the significant contributions made by farmers to the country and their ongoing lack of social benefits as reasons for the socialist government to assume more responsibility.

Guo emphasized that over 500 million urban and rural residents—most of whom are farmers—have made significant contributions to China’s economy and wealth accumulation. “During the planned economy period, there was a sharp price difference between goods in rural and urban areas, and even after the reform and opening up, the dual-track system still exists to some extent. A typical example of this is the migrant worker system. They are workers who live and work in cities but do not enjoy the same rights as urban residents,” he said.

Xu Shanda, another retired former vice minister, noted in 2022 that farmers had made huge sacrifices without being adequately compensated. “In the early years of industrialization, farmers supported urban workers and rural areas supported cities. Basically, wealth created in agriculture and by farmers was drawn to industrialization without compensation,” Xu said in a lecture at the time, adding that farmers also contributed compulsory labor at the government’s order.

“China’s state-owned capital also carries an implicit debt towards farmers,” Xu added.

Guo’s remarks follow increasingly vocal calls to address the country’s most vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. David Daokui Li, a senior professor at Tsinghua University, in a widely circulated video in January, argued that Beijing should allocate an additional 1.25 trillion yuan ($170 billion) annually to raise the monthly pensions of 130 million retired farmers to 800 yuan ($110). Li, a Harvard-trained economist, characterized this amount as “relatively modest compared to China’s total annual fiscal expenditure of nearly 30 trillion yuan.”

In the viral video, Li also highlighted the striking inequality among three distinct groups in China, where the government has rhetorically championed “common prosperity” in recent years.

“On average, rural elderly aged 60 and above receive less than 200 yuan per month, while the average pension for employees of private enterprises is just over 3,000 yuan—which is not particularly high, but still significantly higher than 200 yuan. Meanwhile, pensions for government officials and public institution employees average over 6,000 yuan, highlighting a significant disparity,” Li said.

Earlier this month, a Chinese non-governmental think tank convened 10 experts, including several retired vice ministers, to discuss the next steps for rural pension reform in China. The content of the discussion has not been made public.

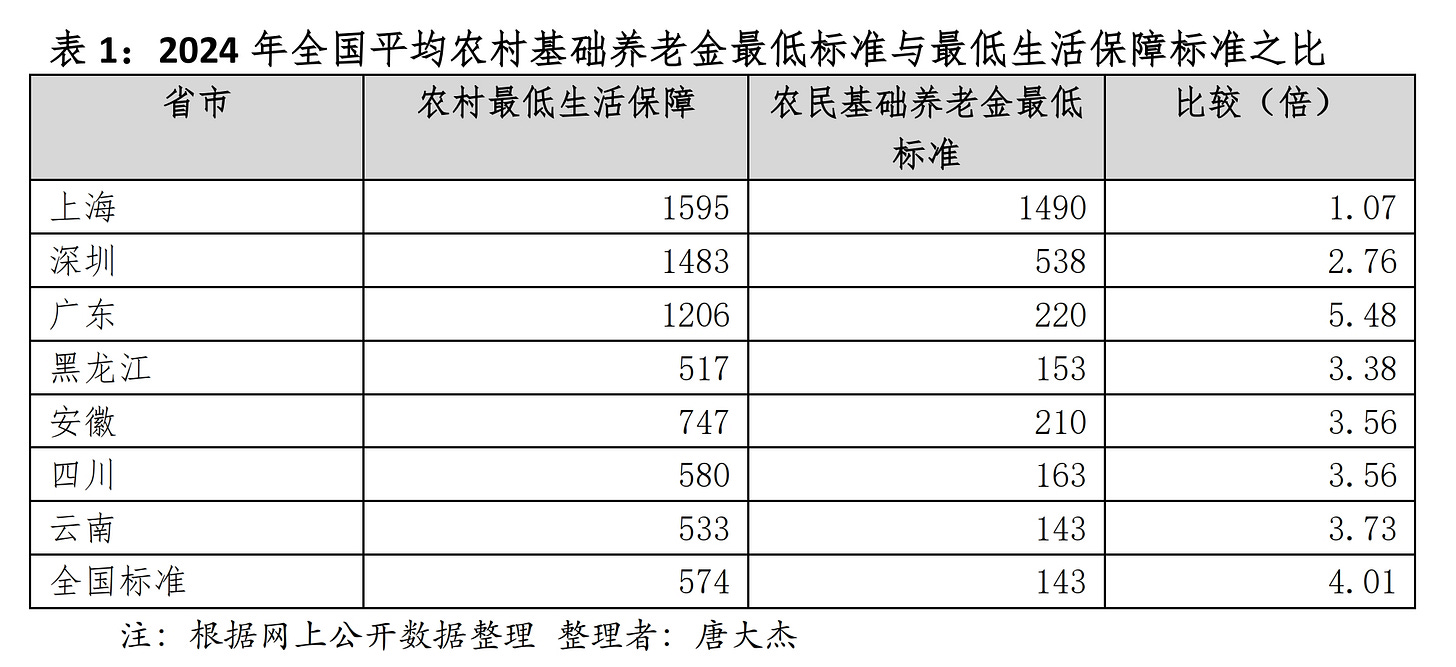

Despite China’s reputation for centralized governance, its pension system—like its medical insurance and other social safety nets—remains highly fragmented. Each of its 30-plus provinces is responsible for its own standards and payouts, creating large disparities. For instance, the lowest pension for farmers in Shanghai is 1,490 yuan ($205), ten times that of southwestern Yunnan province’s 143 yuan ($20).

Nevertheless, in every province, the pensions for farmers are still less than the provincial minimum livelihood allowance, according to a recent op-ed in Caixin, China’s leading business magazine.

Proponents of raising farmers’ pensions have also framed the issue as a crucial step in boosting domestic demand, a central economic priority for Beijing at present. “Increasing farmers’ pensions will boost consumption, and the resulting increase in fiscal revenue will partially offset the costs. Therefore, this is not a costly endeavor overall and is highly beneficial to China’s economic development,” Li said in the January video. “I hope these calls for action can be realized as soon as possible.”

Realistically, it is unlikely that the Chinese government, already under financial strain due to declining land sales, will significantly increase farmers’ pensions in the near future.

In recent months, Beijing has acknowledged, at least on paper, that stimulating domestic demand should be its top priority. However, substantial policies to boost residents’ income remain absent, as the government remains cautious about taking on excessive debt. Proposals to enable Chinese citizens’ direct access to the shares of the country’s vast state-owned enterprises remain unheeded.

The Chinese government does, however, seem more willing to have indebted Chinese families to borrow more, relaxing real estate purchase restrictions and bank credit, including consumer loans. (Enditem)

This kind of debate is also going on in Germany—another export-driven economy—but in a completely different way. Germany has actually been too generous, to the point where it discourages low-income workers from taking jobs.