China's Land Finance by Lan Xiaohuan

Book excerpt from "Embedded Power: Chinese Government and Economic Development"

Pekingnology is privileged to publish an excerpt from the 2021 Chinese bestseller《置身事内:中国政府与经济发展》Embedded Power: Chinese Government and Economic Development by 兰小欢 Lan Xiaohuan, Associate Professor (with tenure), School of Economics, Fudan University.

Many prominent Chinese opinion leaders have recommended the book as well as Lan, who earned his Ph.D. in Economics from the University of Virginia in 2012.

Wang Shuo, Chief Editor of the respected Chinese media Caixin, recommended it as “revealing, in layman language, how the Chinese economy's biggest actor - the government - plays its role in keeping pace with the country's economic development. If I were to guess, the title of the book has two levels of interpretations: one level is to put oneself in the situation to understand the actions of the government, and the other, is to grasp how the consequences impact everyone."

The following part, from the second subchapter of the second chapter, explains 土地财政 Land Finance, a phenomenon unique and critical to China's urban development. The term is also perhaps one of the highest frequency words in analyzing the Chinese economy, its skyrocketing urban housing prices, its once red-hot but now defaulting real estate developers, and the dynamics behind local governments' economic decision-making.

Pekingnology thanks Lan for the generous authorization of publishing this excerpt, and Pekingnology is alone responsible for the quality of the translation.

土地财政 Land Finance

The tax-sharing reform (in 1994) did not alter the local governments' central task of pursuing economic development but did diminish their disposable financial resources. While the transfer payments and tax rebates from the central government help close the deficit within the local budget, considerable expenses associated with developing the economy, such as investment attraction and land development, require the local governments to raise extra money.

The local governments might attempt to collect more taxes, and while part of the added revenue would have to go to the central government (as a result of the tax-sharing reform), they would still get more. Local governments could also boost their revenue outside the budget in a variety of ways, and the most significant one is (the so-called) "land finance," income from land transfer and development.

Investment Attraction and Taxation

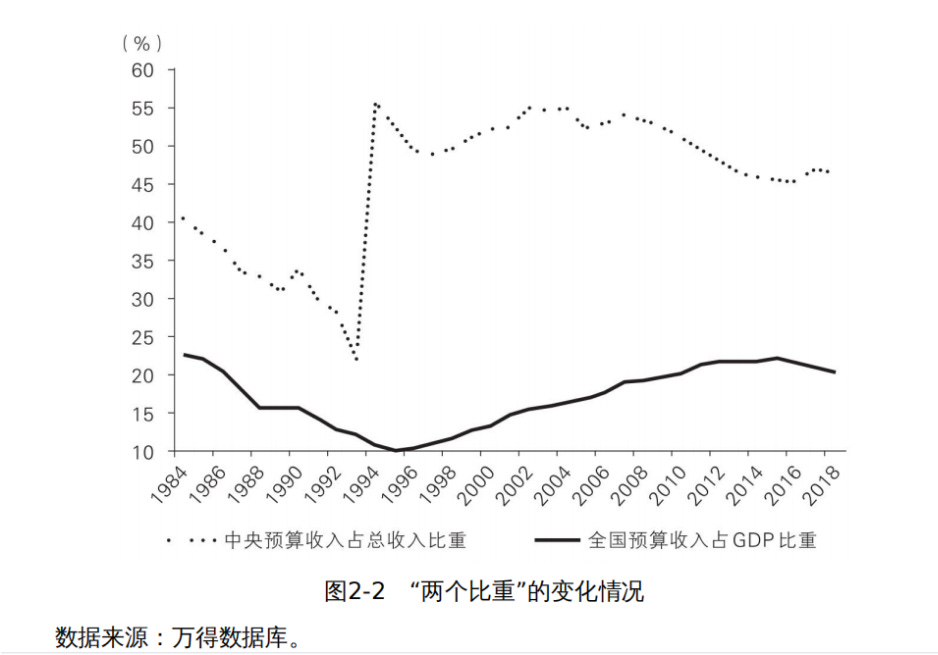

Given a fixed tax rate, the government needs to either expand tax sources or strengthen the tax collection to increase tax revenue. Since the tax-sharing reform, the proportion of national budgetary revenue to GDP has gradually increased (see Figure 2-2), partly due to the strengthening of tax collection, but more importantly, because of the expansion of tax sources.

Figure 2-2

…… Central budgetary revenue to all government revenue

—— National budgetary revenue to GDP

(Source: Wind)

Before the tax-sharing reform, most taxes from enterprises went to the tax authorities associated with the enterprises’ organizational affiliations; after the reform, taxes went to local authorities, which naturally encouraged local governments to attract investment. Local governments favor the manufacturing industry, characterized by heavy assets because it involves a large scale of investment, which helps significantly boost the regional GDP. Additionally, the value-added tax is collected in (every stage of the supply chain, including) production, so big manufacturing brings higher tax revenue. Also, manufacturing not only absorbs low-skilled workers from agriculture but also stimulates the growth of the tertiary industry, which additionally increases the tax revenue.

Since most taxes are collected from companies and particularly in production, the local governments put more attention on companies and manufacturing over people's livelihoods and consumption. Consider value-added tax as an example. While companies can make deductions and the consumers ultimately bear the burden, that VAT is collected in production makes local governments more interested in the companies' location rather than the customers’.

This type of tax policy that prioritizes manufacturing incentivizes local governments to compete with one another in pouring investment into manufacturing and launching large projects, thus promoting the rapid development of the manufacturing industry. Thanks to internal and outside factors such as sufficient and efficient labor and rearranged global industrial chains, China has surpassed the United States in three decades to become the world's largest manufacturing country.

Nevertheless, China also paid a corresponding price. For instance, to compete for large industrial projects and tax revenue, local governments relaxed supervision on environmental protection, leading to ecological damages and overcapacity. Between 2007 and 2014, more than half of local governments' tax revenue from the industry came from industries with overcapacity. High industrial pollution correlated with areas with high local financial pressure. Taxes from companies accounted for over 90% of local governments' tax revenue and almost all of the local governments' non-tax revenue, such as land transfer fees and operating income from state-owned capital.

In addition, employers paid more to social security schemes than employees did. As a result, during the first few years after the tax-sharing reform, local governments tilted their fiscal expenditure towards investment attraction (such as infrastructure construction, corporate subsidies, and so on). In contrast, the spending on people's livelihood (education, health care, and environmental protection) lagged.

In 2002, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China proposed the "Scientific Outlook on Development," requiring "coordinating economic and social development and the harmonious development of man and nature." and ordering more emphasis on expenditure for people's people's livelihood.

Due to the economies of scale and information complexity discussed in Chapter One of this book, local governments are responsible for people's livelihood expenditure. As a result, its share of local government's expenses increased substantially since 2002, from 70% to 85%. (Figure 2-1).

Figure 2-1 Local public budget to national budget

…… Local budgetary revenue to all government revenue

—— Local budgetary expense to all government expense

(Source: Wind)

After the tax-sharing reform, resources for the local governments to develop the economy were squeezed in several aspects.

First, the focus of budgetary expenditure shifted from supporting production and construction to funding public services and people's livelihood. In the late 1990s, "economic development expenses" made up 40% of the fiscal expenditures, while "social, cultural, and educational expenses" (science, education, culture, health, and social security) made up just 26%. By 2018, "social, cultural, and educational expenses" had increased to 40% of the total, while "economic development expenses" dropped.

Second, before the tax-sharing reform, companies paid taxes and paid significant fees to the local government. This extra-budgetary revenue declined dramatically after the reform.

Additionally, since the middle and late 1990s, township and village enterprises reformed to the effect that they did not have to share their profit with local governments any longer, further reducing the local governments' extra-budgetary revenue.

Lastly, starting in 2001, the central government took 60% of income tax revenue, which aggravated the local government's financial pressure. As a result, the local governments had to seek alternative funding resources.

Against this background, "land finance" came to the stage.

What Is Land Finance?

China maintains public land ownership, meaning the state owns urban land, and collectives own rural land. Agricultural land must first be turned into state-owned land via land acquisition before being utilized for industrial and commercial development or residential building. (this has been changed after the amendment to the 《中华人民共和国土地管理法》 Land Administration Law of the People's Republic of China adopted in 2019, see details in Chapter Three).

That is why state-owned land is significantly more precious than agricultural land. How come we have a land system in which urban and rural regions are separated? There was no earth-shattering grand design; it was just a step-by-step evolution since the 1982 Constitution.

[Article 10 Land in the cities is owned by the State. Land in the rural and suburban areas is owned by collectives except for those portions which belong to the State as prescribed by law; house sites and privately farmed plots of cropland and hilly land are also owned by collectives.]

Although each step of the change was justifiable and aimed at solving problems at the time, this land system has resulted in enormous urban-rural disparities, skyrocketing urban housing costs, and a variety of vexing challenges.

In 2020, the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council issued the《关于构建更加完善的要素市场化配置体制机制的意见》Opinions on Improving the Systems and Mechanisms for Market-based Allocation of Factors of Production, which above all highlighted "advancing the market-based allocation of land factor."

The first item was to break the current urban-rural separation and "establish and improve a unified urban-rural construction land market. " Clearly, policymakers are well aware of the existing system's problems. Chapter Three will discuss the relevant reforms in depth.

The tax-sharing reform in 1994 granted local governments the power to decide on and profit from the transfer of state-owned land. At the time, this revenue was negligible. While township and village businesses were flourishing during that period, they all operated on rural collective land designated rather than urban land. Additionally, although local governments could sell urban land-use rights for money at the time, they did not make much money from land sales because they sold them cheap to attract investment, especially foreign investment.

1998 saw two big events, which gradually highlighted the value of urban land. The first was that welfare-oriented housing distribution (people pay the lower-than-market prices to get apartments, or even for free, from their employers) ended.

Monetization of housing benefits (from employers to employees) signified the beginning of commercial housing and the real estate industry. From 1997 to 2002, the average annual growth rate of newly constructed urban housing areas was 26% - increasing almost four times in five years.

The second event was the implementation of the revised《中华人民共和国土地管理法》Land Administration Law of the People's Republic of China, which banned non-agricultural construction in rural collectives-owned land. The revision stipulated that for agricultural land to be converted into land for construction, it must first be converted into state-owned land through the land acquisition process, which established the government's monopoly over non-agricultural construction on Chinese land.

In 1999 and 2000, the revenue from the transfer of state-owned land was low (Figure 2-4) because China had not fully adopted the "bidding, auctioning, and listing" system for land transfers.

The land transfer process was opaque, and real estate developers took advantage of that and worked their way. For example, some developers took advantage of the reform of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) to get the land from the SOEs and then obtained the license from the urban planning department. Like that, they were able to develop real estate by paying just a tiny amount of land transfer fees following the state's rules (because the land wasn't auctioned directly by the local government but transferred from the SOEs). That's a process involving huge profits with the land changing hands, and the corruption was massive.

Figure 2-4 Proportion of revenue from state-owned land transfer to local public budget revenue

Data source: 《中国国土资源统计年鉴》China Land and Resources Statistical Yearbook over the years.

In 2001, to curb corruption and chaos in land development, the State Council proposed "vigorously implementing bidding, auctioning, and listing." The following year, the Ministry of Land and Resources stipulated that four types of land for business use (commerce, tourism, entertainment, and real estate) must be obtained through the "bidding, auctioning, and listing" system. As a result, local governments started expropriating lands from farmers and then selling them to developers. "Land finance" began to grow. Such income from land transfer dramatically increased from 2001, and by 2003, it accounted for 55% of the local public budget revenue. (see Figure 2-4).

After the 2008 global financial crisis, stimulated by fiscal and monetary policies, revenue from land transfer climbed to a new level, reaching 68% of local public budget revenue in 2010. Although the proportion declined in the past two years, the absolute amount still increased, reaching 6,291 billion yuan in 2018, which was 2.3 times higher than in 2010.

The "land finance" includes tremendous revenue from the transfer of land use rights and various tax revenues related to land use and development. Most of these taxes were based on the value of the land rather than the area, so the taxes surged as the land value did. Such taxes can be divided into two categories. One is related directly to the land, including land value-added tax, urban land use tax, farmland occupation tax, and deed tax. 100% of them flew into local governments. In 2018, these four categories of tax revenue amounted to 1,508.1 billion yuan, which was 15% of the local public budget revenue, a considerable number.

The other type is related to real estate development and construction companies and mainly involves value-added tax and corporate income tax. In 2018, the local government's portion of these two taxes (50% of the value-added tax and 40% of the corporate income tax) accounted for 9% of the local public budget revenue.

If we count these taxes and land transfer income as the total of "land finance," then such "land finance" revenue in 2018 was about 89% of the local public budget revenue, which was indeed the "second (local) Treasury."

Although the land transfer generates revenue, local governments are responsible for related expenses, such as compensations for land acquisition and demolished structures on the land and primary land development expenses.

Those expenses include, for example, "seven connections and one leveling" (referring to primary infrastructure constructions/establishments, like water, gas, road, electricity, internet, etc.).

During the past few years, the expenses related to land transfer were generally equal to or even higher than the revenue.

In 2018, the revenue from the transfer of state-owned land-use rights was 6,291 billion yuan, whereas the expenses were 6,816.7 billion yuan. That alone creates a deficit for local governments. Of course, local governments are beyond making money by selling land - what they wanted are industrial and commercial economic activities after the land development.

"Land finance" began to account for a significant portion of the revenue in the early 21st century. After the income tax reform in 2001, the central government furtherly centralized power and took 60% of the corporate income tax. Since then, the local government has changed from "industrialization" to "industrialization and urbanization" to develop the economy.

On the one hand, it kept selling a large amount of industrial land at a low price to attract investment continuously; on the other hand, it restricted commercial-residential land supply. It extracted monopoly profits as the land price rose.

Over the years, the industrial land area accounted for almost half of the urban land sold. Still, the price was meager: in 2000, it was 444 yuan per square meter, and in 2018 it was just 820 yuan, an increase of only 85%.

However, the price of commercial land increased by 4.6 times, and the residential land price increased by 7.4 times (see Figure 2-5).

Figure 2-5 Quarterly average transaction price of land transfer in 100 key cities, in yuan/square meter

…… Commercial land

—… Residential land

—— Industrial land

(Source: Wind)

Although commercial-residential land only accounted for half of the transferred land area, it contributed to almost all the income from the land transfer. Therefore, "land finance" is, in fact, "real estate finance."

All local governments subsidize industrial land to attract investment, promoting the rapid development of the manufacturing industry. With industrialization and urbanization, many people came into economically developed areas, where the supply of residential land was insufficient, which logically led to soaring housing prices and land prices. Residential land prices skyrocketed and made headlines. Chapter Three will analyze the problems and the solution.

Taxation, Rent, and Competition among Local Governments

Let's pause here and look at what local governments were doing exactly. Economic development is nothing but improving resource use efficiency and trying to "make the best use of talents and materials." China has relatively poor natural resources, and in the initial stage of economic development, the usable resources were mainly people and land. Many significant reforms focused on liberalizing these two factors and enhancing their use efficiency in the past few decades. Compared with people, the land is easier to capitalize on, turning the future income into today's high land price for local governments to use. Although "land finance" created various problems, it was an important source of funding for the fast urbanization and industrialization in the past few years.

As mentioned above, local governments would use all available resources to attract investment and implement urbanization. Therefore, they will consider both land and tax revenues and keep the balance between them to maximize overall income. Local governments sell industrial land at low prices because industry plays an essential role in driving economic transformation and upgrading, bringing value-added tax and other taxes, and creating jobs.

Moreover, there is a large room for industrial productivity to improve, and industry has a strong learning effect, which can promote local modernization, stimulate the local service industry, and bring up the price of commercial and residential land.

Industrial production is characterized by long upstream and downstream chains, remarkable industrial clustering effects, and economies of scale. Suppose a region can develop a unique industrial cluster (such as ceramics in Foshan, south China's Guangdong Province). In that case, the area will have a long-term competitive advantage and a stable source of tax revenue.

Besides, the competition for investment attraction among local governments is very fierce. Although local governments monopolize both industrial land and commercial-residential land, there are many places where industrial companies can settle, so it is difficult for local governments to raise land prices in the competition for investment. However, commercial-residential land is different in that it mainly serves residents in the local areas. Hence, the local governments have a more substantial monopoly over land, making it easier to raise land prices.

The economist 张五常 Steven N. S. Cheung has a metaphor: the local government is like a shopping mall, and the investment attraction strategy brings in tenants. Tenants only have to pay a low entry fee (similar to the transfer fee for industrial land). Still, they must share the operating income with the shopping mall (identical to value-added tax, and as long as the tenant is in business, it has to share the revenue, no matter if it's profitable).

Shopping malls want to maximize the overall income, so they have to consider the balance between tenants' entry fees and rent and the balance among different tenants. Some famous tenants can bring more customers to the shopping malls. In these cases, the shopping malls may exempt such tenants from the entry fee and reduce their part of the shared income and even subsidize the tenants (similar to the various subsidies given to businesses by local governments).

[This is sourced by Pekingnology from “The Economic System of China” by 张五常 Steven N. S. Cheung: A vivid example to illustrate the intensity of competition among the xians/counties is that of shopping malls. A xian/county may be viewed as a large shopping center, under the umbrella of one corporation. Tenants renting shop spaces in the center are the equivalent of investors in a xian/county. The tenant pays a fixed minimum rent (the equivalent of an investor paying a fixed land price), a share rent on top (the equivalent of value-added tax), and we all know the shopping center owner is careful in selecting tenants and tries to accommodate tenants in many ways because of share contracting. And, like shopping centers offering special deals to anchor stores, xians/counties offer special deals to investors who they consider to be big draws. If a whole country is filled with such shopping centers, doing similar business but with the entities being separate, the intensity of competition among them would be very strong indeed. ]

Local governments use taxation and land to attract investment in their respective jurisdictions. Furthermore, the governments at different levels are held responsible by their upper layers and enjoy the related benefits. That such a model effectively promoted the economy after the tax-sharing reform is convincing.

However, year after year, the drawbacks and limits of this model are more and more evident and require reforms.

The first problem was local governments' debt (see Chapter Three). The capitalization of land is, essentially, to mortgage future years' income to borrow money at present. If the borrowed money is invested in high-quality projects and transformed into valuable assets and higher income in the future, then such debt is not a big deal.

However, local officials have limited terms, which will inevitably lead to short-sighted behavior, such as borrowing excessively to carry out big projects and approving superficially good-looking but functionally useless projects. Current officials would harvest ostensibly good results, but the officials in the future would encounter many problems.

As a result, the quality and outcome of the investment decreased, and local governments' debt burden increased.

It wouldn't be too difficult to handle if it was just a debt problem. In recent years, a series of fiscal and financial reforms have effectively held back the rapid debt growth. However, economic growth slowed down, indicating that the efficiency of resource use is still low. Taking land as an example: although the local governments want to allocate land resources effectively and balance the supply of industrial and commercial-residential land, it isn't easy to optimize the allocation of land resources and construction land across the country. There is economic competition between regions, but land use quotas cannot flow among provinces to more desirable areas.

For instance, the Pearl River Delta and the Yangtze River Delta economy have multiplied, with many people moving in. Still, there is not enough construction land quota, which constrains both the industrial and population capacities.

As an international metropolitan, Shanghai uneconomically retains 2.896 million Mu (about 194 thousand hectares) of farmland as of 2020. At the same time, there are many idle or even abandoned industrial parks in China's vast and scarcely-populated central and western regions, whose land-use quotas could have been allocated to more economically developed areas.

If a competition cannot enable resources to transfer to more efficient places, this is different from market competition and cannot sustainably increase efficiency in the long run.

In recent years, as soon as China tightened investment, the drivers for the economic growth would immediately take a hit. The system has always been like this; why did China not have a similar problem in the past?

Well, because the stage of economic development has changed. In the early stage of industrialization and urbanization, since the productivity of traditional agriculture was low, as long as agricultural land turned into industrial and commercial land with industry and commerce replacing agriculture, the efficiency shot up considerably.

However, market competition grew fiercer as industrialization deepened, and there was a higher and higher requirement for technology. Companies need not only land but also many other factors to succeed, such as industrial agglomeration, R&D investment, technological upgrade, logistics, and financial support, which were not available in many places. Without them, what good is a lot of construction land quotas?

The direction of reform is clear. In 2020, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council issued《关于构建更加完善的要素市场化配置体制机制的意见》 Opinions on Improving the Systems and Mechanisms for Market-based Allocation of Factors of Production, which put "promoting the market allocation of the factor of land" in the priority. The guidelines require breaking down the market barriers among urban and rural construction lands within the province, city, and county to build a unified market. The Opinions also require utilizing the stock of construction land and that "a national mechanism for cross-region trading of construction land quotas and supplementary quotas for arable land shall be established." That aims to improve the allocative efficiency of land resources throughout China. (Enditem)

Is there an English translation of this book? I can't seem to find it.