Chinese economy hinges on market reform & rule of law, NOT monetary or fiscal policy, says Zhang Weiying

Interest rate, govt spending, consumption, and housing are all SECONDARY to freedom and law, the prominent PKU economist highlights, adding Beijing should actively shape its external environment.

Zhang Weiying is among the most prominent economists in China. Beyond shaping China’s critical economic reform trajectory from the 1980s to the 1990s, he co-founded the China Center for Economic Research (CCER), the predecessor to the current National School of Development (NSD), and served as the Dean of Guanghua School of Management, both at Peking University.

Around 2018 and 2019, the Boya Chair Professor of Economics famously criticized the so-called “China Model” as the wrong interpretation of China’s success since its reform and opening up.

“It is the marketization and development of non-state sectors, rather than the strong power of government and the state sector, that have driven the Chinese economy to grow fast and to be increasingly innovative. If China wants to sustain its economic performance, it must stay on the way to continuing marketization. Otherwise, China will fall into stagnation,” Zhang wrote in the Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies in 2019.

In an August 30, 2024 speech to the Class of 2024 EMBA students at NSD, Zhang passionately discussed the distinction between first-order and second-order issues in China’s economy, drawing an analogy from mathematics. First-order issues pertain to fundamental principles and systems, such as whether to uphold market-oriented reforms and the rule of law. Second-order issues involve specific policies like fiscal and monetary adjustments or sectoral interventions. He emphasizes that while most economic discussions in China today focus on second-order issues, China’s economic challenges primarily stem from unresolved first-order issues.

Zhang argues that recent policy efforts have failed to restore entrepreneurial confidence because they neglect the foundation of China’s market economy. First-order issues require addressing core systemic challenges, such as market liberalization and the rule of law, which foster sustainable growth and innovation. He revisits China’s reform history to illustrate the transformative impact of resolving first-order issues. Key milestones, including Deng Xiaoping’s reforms, the shift toward a market economy, and China’s WTO accession in 2001, drove significant economic surges. These reforms - not interest rate adjustment or fiscal spending - integrated China into the global economy, leveraging international markets, technology, and talent. This openness dramatically boosted wealth, living standards, and the value of labor and land.

Zhang underscores the complementary roles of “opening up” and “internal liberalization.” While “opening up” integrates China globally, “internal liberalization” decentralizes decision-making, unleashes entrepreneurial potential, and enhances market dynamics. Together, these principles have been central to China’s success.

Looking forward, Zhang advocates focusing on first-order reforms, such as enhancing economic openness and strengthening legal and institutional foundations. He warns against insular development and the dangers of the “Thucydides Trap” mindset, urging China to prioritize global cooperation and entrepreneurial confidence to sustain long-term prosperity. “No nation is predestined to be our friend, nor is any nation destined to be our enemy. Everything depends on our choices and actions,” he says, and China’s international environment depends on its own choices and actions.

The lack of confidence in the Chinese economy, which Beijing has publicly and repeatedly recognized, according to Zhang, depends on sound principles, not short-term policy interventions: “When freedom expands and the rule of law progresses, confidence naturally grows. Conversely, when freedom contracts and the rule of law regresses, confidence wavers.”

All highlights below are mine. - Zichen Wang

张维迎:中国经济的一阶问题和二阶问题

Zhang Weiying: First-order and Second-order Issues of China’s Economy

Today, I will talk about the first-order and second-order issues in the Chinese economy.

In mathematics, functions are used to describe relationships between variables. If a function is differentiable, its fundamental characteristics can be depicted using the first and second derivatives, and some functions even have third or fourth derivatives. The first derivative determines the direction of change, whether increasing or decreasing, while the second derivative reflects the rate of change, that is, the speed of increase or decrease. Suppose there are two functions with time as the independent variable, both having positive second derivatives but negative first derivatives. This implies that the first function’s value rises over time and accelerates as it rises, whereas the second function’s value falls over time but decelerates as it falls.

Applying these mathematical concepts, China’s economy similarly involves first-order and second-order issues. First-order issues pertain to the principles and system China adopts: whether to develop a market-oriented and law-based system or to retreat towards the planned economy and rule of man. Second-order issues, on the other hand, relate to specific economic policies, such as how to use fiscal and monetary policies to stimulate investment and consumption, how to boost exports, and how to address challenges in specific industries like real estate.

First-order issues concern the "way" (道), while second-order issues concern the "technique" (术). Current discussions in the field of economics largely focus on second-order issues, with first-order issues often overlooked. This phenomenon may stem from two factors.

The first is cognitive limitation. Constrained by the tenets of Keynesian macroeconomics, many economists and government officials believe that addressing economic downturns lies in stimulating investment, promoting consumption, and supporting industry development (such as AI and the real estate industries). Thus, their focus is on how to adjust the economy using tools like monetary and fiscal policies.

The second is avoidance. As first-order issues are more sensitive and difficult to discuss openly, people often assume their nonexistence. However, recent practices suggest that focusing solely on second-order solutions cannot fundamentally resolve China’s economic challenges. Although economists differ on policy details, their recommendations are generally based on the Keynesian framework, and the results have been less than satisfactory. Despite frequent policy measures, entrepreneurs' confidence remains low, primarily because first-order issues remain unresolved.

China's Economy: Opening Up and Internal Liberalization

To gain a deeper understanding of the distinction between first-order and second-order issues, it is necessary to revisit the history of China’s reform and opening-up since 1978.

What is the fundamental issue that China's reform and opening-up aims to address? In my view, it primarily seeks to resolve the first-order issues in China's economic development rather than the second-order issues.

In the 1980s, there was intense debate over the choice of reform paths, which can be understood as a struggle between reformists and conservatives. In my view, the core disagreement between these two factions lies in whether the focus should be on resolving first-order or second-order issues. The reformists advocated addressing first-order issues through fundamental changes at the conceptual and systemic levels, transitioning gradually from a planned economy to a market economy, reducing direct government intervention in the economy, and granting entrepreneurs greater freedom of choice. In contrast, the conservatives concentrated on solving second-order issues, such as improving the planned economy, enhancing the scientific precision of planning, ensuring government fiscal stability, and avoiding economic policy mistakes like those of the late 1950s to early 1960s.

Deng Xiaoping's proposed solution to the first-order issues can be summarized in the principle of "opening up and internal liberalization." (“对外开放,对内放开”). Here I want to emphasize that the term "internal liberalization" may more accurately capture the essence of the reforms than the commonly used "revitalizing domestic economy" (“对内搞活”).

Opening Up

Opening up is, first and foremost, a principle and a belief system. It is grounded in the conviction of the universal values of human civilization, the idea that the advanced experiences and technologies of Western countries can aid China’s development, the belief in cooperation over confrontation, the aspiration to turn adversaries into partners, and the vision that an international environment featuring "peace and development" is achievable through efforts. Notably, an international environment featuring "peace and development" is not just an observation or a natural occurrence but a goal China strives for—an outcome that can be realized through the efforts of all countries. Without the reform and opening-up policy, and had China persisted with the approaches of the 1960s and 1970s, the international environment might have been entirely different, with "peace and development" likely out of reach.

Guided by this principle, China's policy of opening up aimed to integrate the country into the global economy, leveraging international markets, foreign capital, and the advanced technologies and ideas of developed countries. China established special economic zones and progressively expanded the openness of its coastal cities. It encouraged foreign investment and strengthened comprehensive cooperation with the international community in fields such as talent exchange, education, science, technology, and culture. This facilitated China's connectivity with the world. Notably, beyond introducing technology and capital, the exchange of ideas and concepts was equally, if not more, important. It ushered in a profound intellectual enlightenment for China.

A milestone in this journey was China's accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, marking its full integration into the global economy. As a developing country, China benefited from numerous preferential treatments, reflecting the willingness of Western developed countries to enhance cooperation with China under the principle of mutual benefit.

Looking back over the past two decades, the transformation in Chinese people's wealth accumulation and infrastructure development has been staggering. Joining the WTO was undoubtedly critical in driving China's explosive economic growth. From 2001 to 2008, China underwent a significant economic transformation. This period bolstered its economic strength and optimized the value of previously underutilized resources, substantially enhancing their economic contribution.

It is fair to say that the dramatic surge in Chinese wealth primarily occurred in the decade following its accession to WTO. Before 2001, many cities faced many unemployed workers, and numerous young people struggled to find jobs (a key reason for the 1998 university enrollment expansion). The four major state-owned banks were on the verge of technical insolvency, with capital adequacy ratios far below the international standards set by the Basel Accords. By 2007, however, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) had become the world's largest bank by market capitalization. In 2010, China became the world's second-largest economy in purchasing power parity (PPP) terms. Meanwhile, ordinary people experienced growing prosperity. In 2000, there were 0.5 cars per 100 urban households in China. By 2011, this number had surged to 18.6—an increase of 36 times in just a decade!

Why did Chinese people suddenly feel wealthier in such a short period? Let me use a metaphor to show this point. Imagine a rural elderly woman who owns an antique passed down through generations. If she sells it in her village, it might fetch 300 yuan; in her county, it could sell for 3,000 yuan. As the market expands to the city, province, or country, the price keeps rising. If sold globally, it might fetch 30 million yuan. The same item’s valuation changes with the size of the market. Wealth is not a physical concept measured by weight or area, but a valuation concept determined by the openness of markets and people’s expectations.

After joining the WTO, China integrated into the global economy, enabling a significant portion of its products to be sold worldwide. From 1978 to 2001, China's exports grew at an average annual rate of 15.4%, but after it acceded to WTO in 2001, this rate surged to 27.2% by 2008—more than twice the GDP growth rate.

At the national level, the rapid growth in exports directly fueled a swift accumulation of foreign exchange reserves. When China joined the WTO in 2001, its foreign exchange reserves stood at $212.1 billion. These reserves then grew by hundreds of billions of dollars annually, reaching $3.18 trillion in 2011 and peaking at $3.84 trillion in 2014—a staggering 17-fold increase over 13 years. This massive reserve accumulation provided a solid economic foundation for China and enhanced its influence and voice in the global economy, enabling it to participate in international economic cooperation and competition with greater confidence. While excessive reserve accumulation is not entirely beneficial, it is important to emphasize that China's strengthened position on the global stage and its ability to provide large-scale aid to Africa and other developing regions were made possible by the enormous reserves accumulated after joining the WTO.

After China acceded to WTO, previously undervalued aspects of China’s economy increased in value. What was the most undervalued resource in the past? People. Time is universally equal—every person has 24 hours a day and 7 days a week, regardless of wealth, location, or status. The essence of wealth growth is the increasing value of each individual’s time. The disparity in wealth is essentially a difference in the value of time.

From 1995 to 2000, the annual growth rate of average wages in China’s urban employment units (excluding private enterprises) was 11.8%. However, in the decade following the accession to WTO, this growth rate accelerated to 14.4%. For example, in Beijing’s domestic service sector, the monthly salary of a nanny increased from 480 yuan in 2002 to 4,800 yuan in 2011—a tenfold increase in a decade, with an average annual growth rate of 16% after deducting price factors. This reflects the increase in the value of Chinese people's time.

Compared to the U.S., in 2005, the hourly wage of a manufacturing worker in the U.S. could pay for the wages of 22 Chinese workers. By 2010, this ratio dropped to 10, and by 2015, it further declined to 5, with the current figure likely even lower. In other words, comparative to Americans, the value of time for Chinese workers has significantly increased.

Let’s use another perspective to understand the increase in Chinese wealth. In 2001, a newly launched Nokia 8250 phone cost 3,350 yuan, while the average annual wage of urban workers in China was 10,870 yuan. This meant a year’s wages could buy only 3.2 Nokia 8250 phones. By 2018, a newly launched Xiaomi Mi 8 smartphone cost 2,699 yuan, while the average annual salary of urban workers rose to 82,413 yuan—enough to buy 30.5 Xiaomi Mi 8 smartphones. In other words, the work time required to purchase a Nokia 8250 in 2001 would, by 2018, allow one to buy 9.5 Xiaomi Mi 8 phones, which far surpassed the former in technology and functionality.

The same pattern applies to cars. In 2001, a Santana 1.8 sedan cost 128,900 yuan, requiring nearly 12 years of work for an average urban worker to afford one. By 2009, the price of a Santana 1.8 dropped to 79,800 yuan, while the average urban wage rose to 32,244 yuan—meaning it took less than 2.5 years of work to buy one. By 2023, although the Santana 1.8 model was discontinued, a similar Santana 1.6 model cost 76,800 yuan, while the average urban wage had risen to 120,698 yuan—requiring just 8 months of work to afford one. In essence, the work time needed to buy a Santana 1.8 in 2001 could buy 4.8 cars in 2009 and 18.5 cars in 2023. Using cars as a measure, the value of work time increased by 17.5 times between 2001 and 2023.

Here’s another example using food. Suppose someone works 250 days a year, 8 hours a day, totaling 2,000 hours annually. Using eggs as a reference, in 2000, a Chinese urban worker needed to work for about 144 minutes to buy a pound of eggs. By 2010, this was reduced to just around 33 minutes, and by 2019, it dropped further to about 15 minutes—only about one-tenth of the time required in 2000. In other words, the real price of eggs fell by roughly 90%, or using eggs as a benchmark, the value of a worker’s time increased 8.5 times.

Beyond the increased value of time, land resources in China also changed significantly. After China's accession to WTO, the value of land surged dramatically. Thirty years ago, land in nowadays bustling areas within Beijing’s Third Ring Road might have seemed unremarkable, but now its price per mu can reach millions or even tens of millions of yuan.

The rise in land prices is tied to the rise in housing prices, which often attracts complaints. However, from another perspective, housing prices have risen more slowly than wage increases. In fact, much of the rise in housing prices stems from the increase in people’s income. A comparison between wages and housing prices would illustrate this more clearly: on a national average, in 1998, the annual salary of an urban worker could only buy 3.6 square meters of apartments. By 2012, this number had risen to 8 square meters, and by 2022, it increased to 11.4 square meters. This means that to purchase an 80-square-meter apartment, the required working years dropped from 22 years in 1998 to 10 years in 2012, and then to 7 years in 2022. Although housing prices have generally risen across the country, the more significant trend is the combined increase in personal income and land value, allowing people to accumulate housing wealth in less time. Of course, this is the national average, though exceptions can be found in cities such as Beijing. For instance, in 2013, a year’s average income in Beijing could buy 5.2 square meters, but by 2022, this number dropped to 4.3. Despite Beijing’s high housing prices, its unique advantages and appeal continue to attract people.

With the increase in individual worth, the overall economic strength of the Chinese population has improved significantly, as evidenced by the sharp rise in car ownership. In 1999, urban Chinese households owned an average of 0.34 cars per 100 households. By 2023, this number had risen to 55.9 cars per 100 households. Although this figure has not yet reached the level of the U.S. in 1930 (where there were 60 cars per 100 households), China’s car ownership rate has substantially increased. This achievement is closely tied to the impact of WTO membership and the implementation of opening-up policies. China's accession to WTO not only lowered the prices of consumer goods, such as cars, but also substantially raised workers' wages, thereby accelerating the embrace of modern lifestyles, including car ownership.

Internal Liberalization

The principle of "internal liberalization" begins with a transformation in principles rooted in granting individuals greater freedom. This principle rests on several key beliefs: faith in human autonomy and initiative, trust in human creativity, confidence in the superiority of the decentralized decision-making involving the broader population to the centralized one by a few individuals in offices, belief in the power of the market, and trust in entrepreneurship.

Based on these principles, China began implementing the household responsibility system in rural areas in the late 1970s. In 1984, the commune system was officially abolished, free markets were opened, and farmers were given the autonomy to decide what to plant, which greatly stimulated their production enthusiasm. In urban areas, to unleash entrepreneurial vitality, policies were introduced to expand enterprise autonomy and allow decentralization and interest concessions. Later, the "grasp the large, let go of the small" (manage large enterprises well while relaxing control over small ones) strategy was adopted, encouraging the privatization of small enterprises and transforming state-owned enterprises into the structure of shareholding. Clear principles were established for separating the Communist Party of China and the government, and the separation of government and enterprises, ensuring that each performed its specific duties effectively. Through a dual-pricing system, local governments were given more economic decision-making authority, and the non-state economy was vigorously developed, positioning entrepreneurs as the driving force of economic growth.

The implementation of these liberalization policies effectively alleviated the shortages of goods and limitations on resource allocation in the planned economy era. For example, in grain production, the widespread hunger issues of the planned economy period were fundamentally resolved after the reforms. By 1984, a surplus of grain even emerged, and grain ration coupons ("liang piao") gradually became obsolete. Between 1978 and 1985, grain yield per mu increased by 38%, a testament not only to the immense potential of agricultural production but also to the fact that today's challenges are more about how to use land resources efficiently rather than a scarcity of land. As individuals gained more freedom of choice, market dynamics underwent a fundamental shift. Markets transitioned from being seller-driven to buyer-driven, giving consumers more choices. Producers, in turn, moved from a position of dominance to one of serving customers and meeting their needs. By 1994, all forms of ration coupon systems, including grain ration coupons in use for 39 years, were abolished nationwide, relegating these relics of the past to history.

Opening Up and Internal Liberalization: A Cause-and-Effect Relationship

Opening up and internal liberalization are not two separate first-order issues; rather, they are complementary and interdependent, rooted in a shared core principle: trust in individual creativity, recognition of market mechanisms, and admiration for entrepreneurship. These two aspects are like two sides of the same coin. Without internal liberalization, China could not fully reap the benefits of opening up, nor could Chinese enterprises achieve international competitiveness. In fact, had the existing WTO members not believed that China was moving toward a market-oriented system, it would have been impossible for China to join the WTO. Conversely, domestic reforms would have struggled to advance rapidly or deeply without opening up, and might have even stalled. Joining the WTO was not only a landmark in China’s opening up but also a catalyst for internal liberalization. It prompted the Chinese government to comprehensively review and adjust economic management policies, abolishing regulations inconsistent with WTO rules. This process accelerated the transformation of banks and large state-owned enterprises into a shareholding structure, introduced international strategic investors, and further propelled China’s domestic process towards a market-oriented economy.

Revisiting the Past to Understand the Present: The Key is Still to Resolve First-Order Issues

As China enters 2024, in the face of sluggish economic growth, a reflection on past experiences can clarify that the challenges currently facing China’s economy are still first-order issues—issues of the direction of its principles and system —rather than second-order issues like how to stimulate investment and promote consumption through monetary or fiscal policies, or how to support specific industries and high-tech development.

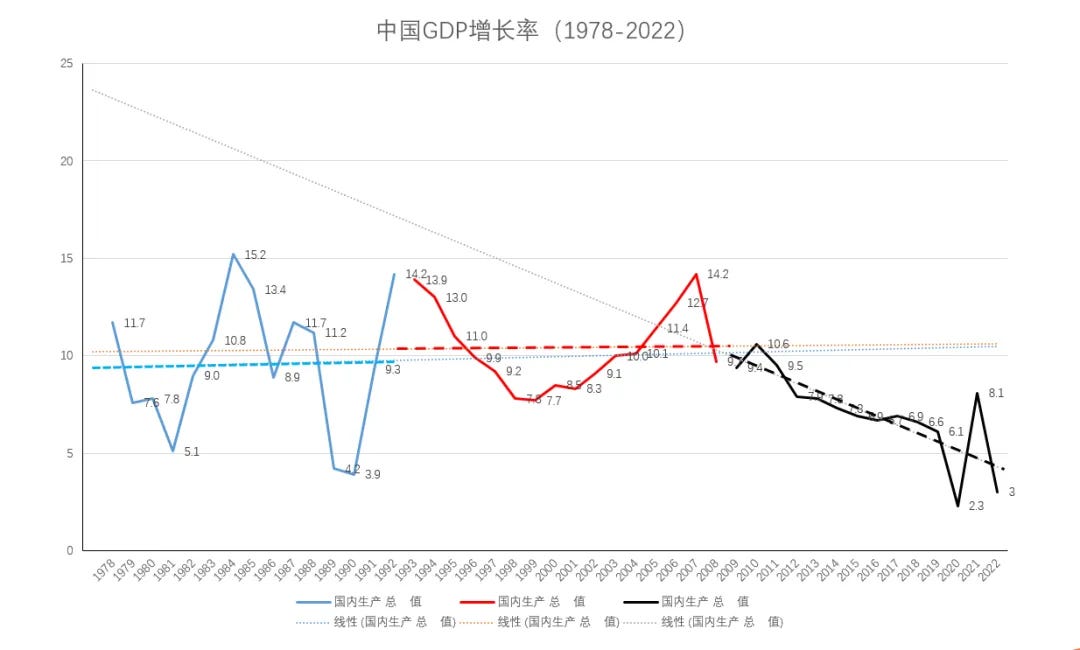

Over the past forty years, China’s economy has experienced three significant growth surges. None of these surges were driven by monetary or fiscal stimulus; rather, they resulted from resolving first-order issues.

The first surge occurred in 1984 and the years that followed. In 1984, with the reform priorities shifted from rural to urban areas, measures were taken among state-owned enterprises, including granting them greater autonomy and "decentralization and interest concessions" (放权让利), while policies like "fiscal responsibility system" (财政包干) and "different local governernments are responsibile for their respective revenue and spending" (分灶吃饭) were also introduced to local governments. The October 1984 Third Plenary Session of the 12th CPC Central Committee set the goal of establishing a "planned commodity economy," marking a decisive step toward a market-oriented economy. In January 1985, the dual-pricing reform was launched, sparking market activity and the rapid growth of township and village enterprises. These were all strategic moves aimed at resolving first-order issues.

The second surge followed Deng Xiaoping’s Southern Tour in early 1992. Deng’s speeches reignited market-oriented reforms, and the 14th CPC National Congress in October of that year formally set the goal of establishing a "socialist market economy." This clarified the reform direction , prompting a wave of government officials leaving office and transitioning into commercial activities, forming the "92 generation of entrepreneurs" (those entrepreneurs that thrived after Deng's Southern Tour in 1992). The privatization of township and village enterprises and the rise of entrepreneurs as the main actors in economic activity were key outcomes.

The third surge began with China’s accession to the WTO in 2001. Driven by the WTO, the Chinese economy was integrated into the global market. From 2002 onward, China enjoyed seven consecutive years of high-speed economic growth, with growth rates accelerating year by year.

I want to emphasize that today’s challenges are no different: to resolve first-order issues requires solutions like "opening up and internal liberalization", rather than running in circles trying to solve second-order issues such as monetary and fiscal policy.

High-level of opening up must go beyond slogans and translate into concrete actions.

We should firmly believe that leveraging global wisdom and resources and participating in the international market is far more beneficial to improving the welfare of the Chinese people than pursuing isolated, self-sufficient development. The towering tree of China’s economy has thrived over the past 40 years precisely because it has drawn nourishment and water from global soil. If its roots are severed, the tree will gradually wither, and its fruits will become increasingly scarce.

Wealth is a matter of valuation and expectations. Transforming a country from poverty to prosperity is not difficult as long as its principles and system are sound. Conversely, it is much easier for a country to fall from prosperity to poverty—Argentina and Venezuela are clear examples.

Like a sports game, to become a champion—or even a runner-up or third-place finisher—a country must have the courage to participate, even if the referees are sometimes unfair. This is no excuse to avoid competing. Participation requires adherence to agreed-upon rules and the readiness to accept failure. No nation is predestined to be our friend, nor is any nation destined to be our enemy. Everything depends on our choices and actions!

I must stress that the currently widespread "Thucydides Trap" mindset is a profoundly destructive notion that could mislead the country. We must free ourselves from this intellectual constraint. The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE), a conflict between the Athenian and Spartan alliances, was not the inevitable result of the rise of a new power, as Thucydides claimed. The war was not inevitable or natural. Instead, it resulted from political leaders' arrogance, resentment, and vengeance-driven attitudes and their ignorance, misjudgments, and third-party provocations. Athens’ excessive greed and unrealistic goals ultimately led to its catastrophic failure in the war.

Donald Kagan, a Yale University scholar, conducted in-depth research on the Peloponnesian War. He found that the politicians involved lacked foresight, mistakenly believing they could achieve significant gains at low costs. They relied on past experiences to craft strategies without adequately accounting for the risks of misjudgments and miscalculations, nor did they prepare contingency plans. Thus, the war's outbreak was neither inevitable nor the result of irresistible forces; it arose from specific decisions made in a particular context.

Similarly, I believe that our current and future international environment depends on our choices and actions.

Currently, a notable issue is the lack of confidence among consumers, which stems not from consumers’ reluctance to spend but from widespread subpar expectations about entrepreneurship, employment, and income prospects. Consumers don’t need economists or the government to encourage spending. The notion that increasing the consumption rate leads to high growth is naïve. In fact, excessively high consumption rates often result from economic stagnation rather than being a cause of growth. If high consumption were the driver of growth, humanity’s economy would have grown rapidly 2,000 years ago when consumption rates were near 100%.

Equally concerning is the lack of confidence among entrepreneurs, which is not due to liquidity issues or high financing costs but rather to insufficient guarantees of personal and property security. Insecurity not only impacts individuals but also undermines the confidence of the entire entrepreneurial community.

Building entrepreneurial confidence depends primarily on the reform direction, not on the strength of monetary policy stimulus. When freedom expands and the rule of law progresses, confidence naturally grows. Conversely, when freedom contracts and the rule of law regresses, confidence wavers. Entrepreneurs' confidence is a cornerstone of China’s economic future, and its stability directly affects sustained economic development and innovation. I have elaborated on this topic in greater depth in my book 《重新理解企业家精神》Re-Understanding Entrepreneurship: What It Is and Why It Matters.