Comparing Women's Choice in Career and Family in China, U.S.

Zhao Yaohui of PKU says the "career funnel" severely limits women's career development in China, calling for overhauling traditional culture, flexible worktime, and affordable childcare.

On Nov. 11, 2023, the National School of Development (NSD) at Peking University hosted a session on the employment and family choices of Chinese women. This event took place amid the escalating challenge of China's declining birth rate, which resulted in a decrease of 2.08 million in the nation's total population in 2023. Additionally, the session's theoretical framework was informed by the work of Claudia Goldin, the 2023 Nobel Laureate, honored for her comprehensive research into women's earnings and their participation in the labor market throughout centuries.

The East is Read, a sister newsletter, has shared the presentation of Huang Wei, an associate professor with tenure at NSD, on the cost of childbearing in China.

We will share the full transcript of the session in Pekingnology and The East is Read. The following is a presentation by Professor 赵耀晖 Zhao Yaohui of NSD. The transcript was originally published in the NSD’s WeChat blog.

The 2023 Nobel Economics Prize was awarded to Professor Claudia Goldin at Harvard University. Compared to the winners of the Nobel Economics Prize over the years, Claudia Goldin's most distinctive feature is that she is a female economist whose research focuses on women's career development and the balance between work and family. In her book Career and Family: Women's Century-Long Journey toward Equity, Goldin reviews the century-long endeavor of American women seeking equality. The speech will explore the themes of women's employment and family life, drawing comparative insights between China and the United States. Building on this, it will discuss the future prospects for Chinese women in these areas. The data on China was compiled by my doctoral student, Bi Rudai.

I. Women's Employment

Differences in employment rates between women in China and the United States

Figure 1 shows the difference in employment rates between men and women in the United States over the period from 1890 to 2004. The vertical axis represents the employment ratio, while the horizontal axis represents the years. The top line in the graph represents males aged 25-44, and it is evident that over this century, men in this age group were almost fully employed in the U.S.

The employment situation for American women, however, was different. Around 1900, the employment rate for women was extremely low. Only about 20% of women aged 25-44 were employed, and the employment rate for married white women aged 35-44 was virtually zero. Over time, the employment rate for American women slowly but significantly increased, reaching close to 80% around the year 2000.

Looking back over more than a hundred years of labor market history in the U.S., women gradually entered the workforce and played an increasingly significant role. This is a widely recognized important phenomenon in labor economics and the focus of many studies.

Figure 2 Employment rates of men and women aged 25-49 in China

Figure 2 shows the employment rates of men and women aged 25-49 in China, primarily based on data from the country's population censuses. The blue bars represent men, with an employment rate staying at around 95%; the orange bars represent women, with an employment rate fluctuating between 80% and 85%.

As can be seen from Figure 2, Since the era of the planned economy, women's employment in China has achieved a notably high level. Since the establishment of the People's Republic of China (PRC) [1949], the government has consistently encouraged women's participation in the workforce. For example, during the people's commune period [1958-1983], all rural women were required to participate in collective labor, and urban women were also expected to work in factories. Although the employment rate of women has modestly declined since the beginning of reform and opening up, it remains slightly higher than in developed countries.

In contrast, the employment rate of women in the U.S. has been a slow and natural increase. The employment rate of Chinese women has been more influenced by the planned economy. The slight decline did not make the rate fall significantly behind.

Differences in employment between university graduates and the group that never receive higher education

The employment rate for university graduates is higher in both countries.

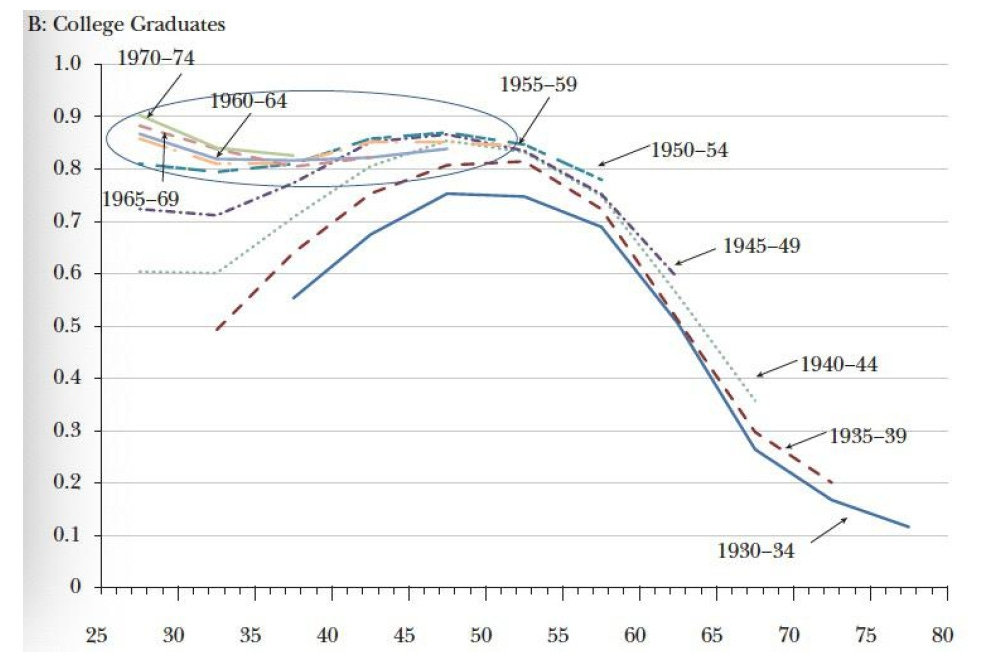

Figure 3 Employment rate of female university graduates in the U.S.

From Figure 3, it can be observed that women born in the U.S. between 1930 and 1934 gradually entered the workforce after the birth of their children. However, for women born between 1970 and 1974, the employment rate was very high immediately after graduation. Their employment rate decreased after having children and increased again as they returned to work when their children were grown. As a result, their employment rate shows a "saddle-shaped" variation.

Figure 4 Employment rate of female university graduates in China

Figure 4, which presents the employment rate of Chinese female university graduates, does not show a "saddle-shaped" trend. Once Chinese female university graduates enter the workforce, they tend to keep working until retirement. This pattern holds for Chinese women without higher education as well.

Gender wage gap

In the 1960s, wages for women in the U.S. were 60% of men's wages. By 2000, this had risen to over 80% of men's wages. The gender wage gap is wider among university graduates, with wages for female university graduates in the U.S. being just over 70% of their male counterparts' wages.

According to data from China Family Panel Studies (CFPS) carried out by Peking University, from 2010 to 2020, Chinese women's wages were about 75% of men's, regardless of education level. By 2020, this percentage had dropped to below 70%, lower than the approximately 80% in the U.S. over the same period. Among university graduates, the situation in China and the U.S. is similar. In 2020, women's wages were about 75% of men's in both countries.

A new phenomenon in the U.S.

In recent two decades, a new phenomenon has emerged in the U.S.: women, in comparison to men, have stopped making progress in terms of employment and wage rates. This suggests that the benefits of policies aimed at women's liberation and eliminating gender discrimination over the past decades in the U.S. have largely been exhausted. The academic community in the U.S. is currently debating why women are no longer advancing, and why the gender gap in employment is not narrowing further. This is also a problem that Goldin cares about.

The background to this problem is the growing income disparity within the U.S. labor market over recent decades, with the primary reason being the sustained high earnings among top-income groups, including lawyers, doctors, and executives in finance and investment banking, which are predominantly male-dominated.

By contrast, women's job choices are constrained by certain objective factors, with childcare emerging as a significant barrier to entering high-income professions. Women with babies find that their income does not reach pre-childbirth levels, while men's wages do not decrease and may even continue to rise. This phenomenon is referred to as the "child penalty" or "motherhood penalty."

This situation is common in the U.S. and many countries in Europe. It tells people that, even in high-income countries, the division of household labor between men and women still exists, with childcare responsibilities primarily falling on women. When children fall ill, it is usually the mother who takes leave to care for them. Many high-income positions lack such leave flexibility, and it is these factors that often limit women's career development.

II. Family

Comparisons in the family aspect mainly include the following indicators:

Proportion of people being unmarried throughout life

Based on the data on the proportions of people who never marry throughout their life given by Chinese officials and reported in Goldin's book for the U.S., using 45 years as a benchmark to assess lifetime unmarried status, the marriage rate of Chinese female university graduates exceeds that of their American counterparts by more than tenfold. Approximately a century ago, about 30% of American female university graduates remained unmarried for life. In recent decades, this percentage has stabilized at around 10%. This trend suggests that American women with a university education have experienced a shift from career to family, while China is seeing an increase in the rate of unmarried women.

Age at first marriage

In the 1920s and 1930s, the average age of first marriage for American women with higher education was around 22 or 23 years old. During the same period, the average age of first marriage for Chinese female university graduates was around 25 or 26 years old, indicating that Chinese women with a university education, while feeling the necessity to marry, were trying to delay their first marriage.

Between the 1950s and late 1960s, the average age for Chinese women at first marriage significantly decreased, a trend likely influenced by the historical context of the Cultural Revolution. From the 1970s to the late 1980s, this age continued to decline steadily, which I presume, might be mainly related to the housing allocation policy under the welfare system of that era. After all, the housing allocation policy prioritized married people, prompting many young people to choose early marriage. After the 1990s, with the end of this policy, the age of first marriage began to rise again.

Proportion of lifetime childlessness

Statistics regarding childlessness among American female university graduates are categorized into age groups: 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, and 40-50. Women in the 40-50 age group who are childless can generally be considered childless for life, so the data from this age bracket can serve as a direct indicator of the proportion of lifetime childlessness.

The data shows that 50% of American women with higher education chose to remain childless for life a hundred years ago. Over time, after a series of declines and increases, the latest trend indicates that American female university graduates are increasingly opting for childbirth.

In China, the proportion of women, regardless of their higher education background, who choose lifelong childlessness has always been quite low. However, in recent years, the proportion of Chinese women choosing lifelong childlessness has shown an upward trend. Among them, women with higher education have a higher proportion of lifelong childlessness than those without higher education. This is an opposite trend compared with that of the U.S.

Number of children born in China

Figure 5

Regarding the number of children women have, there is only the data for China covering women aged 45-64. The solid red line represents the number of children born to women with higher education, while the dashed line represents those without higher education. Among women born in the 1970s, those who are university graduates generally have only one child, while the number of children born to women without a higher education background is around 1.6 to 1.7.

Combining the above indicators, it can be concluded that the vast majority of Chinese women with higher education choose to marry and have children, but they tend to marry later and have fewer children. Although data for the U.S. is not accessible, it is estimated that Chinese women with higher education are likely to have fewer children than their American counterparts, as American women typically have two children.

III. Future Development of Women

Differences in education level between men and women

The future progress of women is closely associated with the quality of human capital quality, and the difference in education levels between men and women is only one of the key aspects. In terms of higher education, over approximately a century, the percentage of individuals, both men and women, pursuing higher education in China and the U.S. Has been slowly on the rise from very low levels. Influenced by special historical backgrounds such as the Cultural Revolution, China has experienced fluctuations but ultimately aligned with that of the U.S. In both countries, a notable trend is emerging among those with higher education: the proportion of women is now exceeding that of men.

The U.S. witnessed this phenomenon as early as the 1980s, but in China it started about two decades later, becoming evident among the people who entered university after 2000. Anyhow, the phenomenon indicates that the level of education received by female human capital has begun to surpass that of men.

Five developmental stages of American female university graduates

Concerning the phenomenon of the number of women with higher education gradually exceeding that of men, there have been many related studies in the U.S. Nobel laureate Goldin also discusses this in her book Career and Family: Women's Century-Long Journey toward Equity, where she identifies five stages in the development of American female university students over a century.

1) Family or Career (For females who graduated in the 1900s-1910s)

American female university graduates who graduated between 1900 and 1910 [sic. should be 1900-1920] often faced a choice between family and career. Data indicates that women of this time knew what they wanted: approximately one-third chose to remain unmarried for life, while half opted for lifelong childlessness. Among childless female university graduates, there was a notably high employment rate, reflecting a decisive choice for career over family; conversely, the employment rate for married women was below 5%, indicating a predominant inclination towards family life.

2) Job then Family (For females who graduated in the 1920s-1945)

Female university graduates from 1920 to 1945 generally chose to work first and then start a family. The rise of manufacturing created numerous white-collar jobs, such as accounting and sales, attracting a large number of women to the labor market. Improvements in living facilities and the proliferation of household appliances like washing machines reduced women's household labor burden, creating objective conditions for female employment. For American women, this was a progressive time. Many women, with high school diplomas, obtained the stepping stone to employment. Simultaneously, the Great Depression incubated laws restricting married women's employment. Institutions such as government and schools would not employ married women workers, resulting in the fact that women had to resign once married.

3) Family then Job (For females who graduated in 1945-1950s)

This stage lasted from the end of World War II to the 1950s. The U.S. experienced a post-war baby boom, with a general trend towards early marriage and pregnancy, partly as an aftermath of the war. Women prioritized family, generally hoping to return to work once their children were grown. With the post-war economic recovery in the U.S., the labor market gradually flourished, and previously unfriendly laws for women's employment were abolished, allowing many women with grown children to re-enter the workforce. However, most of them faced significant challenges upon returning due to a substantial career gap brought by childbirth. Their skills were severely misaligned with the realities of the workplace, making it difficult for them to secure well-paid jobs. This was a significant pain point for women at the time, followed by numerous academic studies addressing their plight.

4) Career then Family (For females who graduated in the 1960s-1970s)

In the 1960s, there was also a cultural revolution in the U.S., with the women's liberation movement being one of the representative trends. Women who graduated between 1965 and 1970 experienced a shift towards liberalized thinking, again leaning towards "career then family." The advent of contraceptives also served as a catalyst, allowing women to date and marry without the urgency of childbirth. With the women's liberation movement, gender discrimination impeding women's career development was also eliminated.

5) Career and Family (For females who graduated in the 1980s-1990s)

Female university graduates in the 1980s and 1990s surpassed their male counterparts in educational attainment, achieving an unprecedented peak in human capital development. The concept of gender equality was deeply ingrained. More women from this generation chose to pursue careers while also marrying and having children. The widespread application of assisted reproductive technologies also helped female university graduates balance career and family.

Insights from a century of American women's development

The five stages mentioned in Goldin's book, from initially having to choose between career and family to eventually balancing both, reflect a significant century-long change.

From these five stages, the following inspiration can be drawn:

First, market demand and technological advancement are important driving forces in enhancing women's employment levels. For example, the expansion of white-collar jobs improved women's employment and indirectly led to higher levels of female education. Technological advancements like household appliances and contraceptives were crucial in liberating women.

Second, competitive job markets help eliminate discriminatory regulations against women. For instance, the post-marriage employment bans that emerged in the second stage were abolished due to competition in the job market and a significant increase in labor demand. Goldin's recent research focuses on the topic of "greedy jobs." These are jobs with no flexibility, requiring employees to be on call and ready to work whenever a client calls, regardless of time or place. Goldin specifically mentions that high-income positions, in particular, lack flexibility. She believes that as women's competitiveness in the market continues to grow, such a situation will also be constrained by the market. Some IT companies in China are already progressively moving away from the 996 work culture [working 12 hours a day (9 am to 9 pm) and six days a week] and increasing job flexibility.

Third, both marriage and childbirth are aspirations for women, and those who choose to remain unmarried or childless are often compelled by circumstances. Only by striving to create a gender-equal social environment can women be potentially empowered to fulfill these aspirations and to balance their careers with family life effectively.

Prospects for the new generation of Chinese women

Traditionally, Chinese women, even in the face of discrimination, had limited options other than marrying and having children. The circumstances for single, childless Chinese women were historically more challenging compared to their American counterparts. However, in the past three decades, there has been considerable advancement in women's workplace status. The proportion of women attaining higher education has exceeded that of men, thanks to the universalization of the Compulsory Education Law and the enrollment expansion of universities in the 1990s. China's accession to the WTO brought a sharp expansion in white-collar jobs, providing many employment opportunities for women.

Despite this, traditional discriminatory attitudes towards women still prevail in Chinese society. Phenomena including domestic violence, gender bias favoring males, and the severe imbalance in gender roles within households persist. Even women occupying high-ranking positions in the workplace are often burdened with the majority of household chores. Discriminatory practices against women are even more common in rural areas.

Additionally, the "career funnel" phenomenon severely limits women's development in the workplace. Taking universities as an example, there are many female Ph.D. holders, but a lower proportion of women among lecturers, even lower among associate professors, and extremely rare among full professors. The same is also true in government departments. The number of women decreases as one moves up to section level, bureau level, and even minister level. The phenomenon warrants people's attention and research.

Personally, the current situation of Chinese women is similar to the fourth stage of American women's development mentioned earlier. Women's abilities have been unprecedentedly enhanced, but discrimination and constraints against women still exist. Under this contradiction, many women may choose to remain unmarried and childless, a trend that might intensify in the future.

Assisting Chinese women in achieving a balance between career and family requires the establishment of a genuinely equitable social environment. To accomplish this, it is crucial to advocate for three key changes:

Change discriminative perceptions and reshape traditional culture. Male elders and other family members must also embrace the concept of gender equality. Mothers-in-law should encourage their sons to do more housework and share their daughters-in-law's household burdens.

Society should create a workplace environment conducive to family development, providing flexible working hours to the greatest extent.

Society must endeavor to offer high-quality, affordable childcare services, addressing the substantial gap that currently exists, particularly for children aged 0-3. This gap often compels many women to abandon promising career opportunities in high-income professions and opt for less competitive jobs to provide childcare.

Our belief is that market and technological advancements can eventually rectify numerous gender-related cognitive and behavioral biases and distortions. However, this process requires a significant amount of time. Therefore, it is imperative for society as a whole to proactively work towards creating a more female-friendly environment. (Enditem)

Feminism by numbers:

1) Number of female self-made billionaires

🇺🇸: 24

🇨🇳: 78

2) Share of female CEOs among top 500 companies

🇺🇸: 5.8%

🇨🇳: 6.9%

3) Share of female STEM graduates

🇺🇸: 27%

🇨🇳: 42.5%

4) Number of top 10 female chess players

🇺🇸: 0

🇨🇳: 5

5) Number of female world champions in men's e-sports category

🇺🇸: 0

🇨🇳: 1

6) Prevalence of actual sexism

🇺🇸: Low

🇨🇳: High

7) Victim mentality

🇺🇸: High

🇨🇳: Low

Total fertility rate (TFR) is lower with longer average education for females, higher GDP per capita, higher contraceptive prevalence rate, and stronger family planning programs. Chinese women have the most education on earth, GDP per capita is doubling every year, they fully understand birth control and the importance of family planning. And they have access to careers that most Western women only dream of.

China well ahead of global average in smashing dominance of male-only senior exec teams

China has made huge strides in cracking down on what until recently was seen as very much an “all boys’ club” at the top levels of corporate management, according to fresh figures published on Thursday by accounting and consulting firm Grant Thornton to coincide with International Women’s Day. They show 88% of Chinese mainland firms now have at least one woman on their senior management teams – considerably ahead of the global average of 75 per cent, and an 11-percentage-point improvement in the past 12 months. (The figures have been tracked annually by Grant Thornton since 1992, which this year polled 4,995 businesses in 35 countries).

In total, 31 per cent of senior positions in China are held by women, unchanged from last year, but again that tops the rest of Asia-Pacific, which has an average 23 per cent of senior posts filled by the fairer sex.