Fosun’s Green Valley Deal: The Risk Isn’t Just Whether GV-971 Works

A decades-long, widely-documented record of “miracle drug” marketing controversies and regulatory trouble may be what the market is really pricing - but where is Fosun's disclosure?

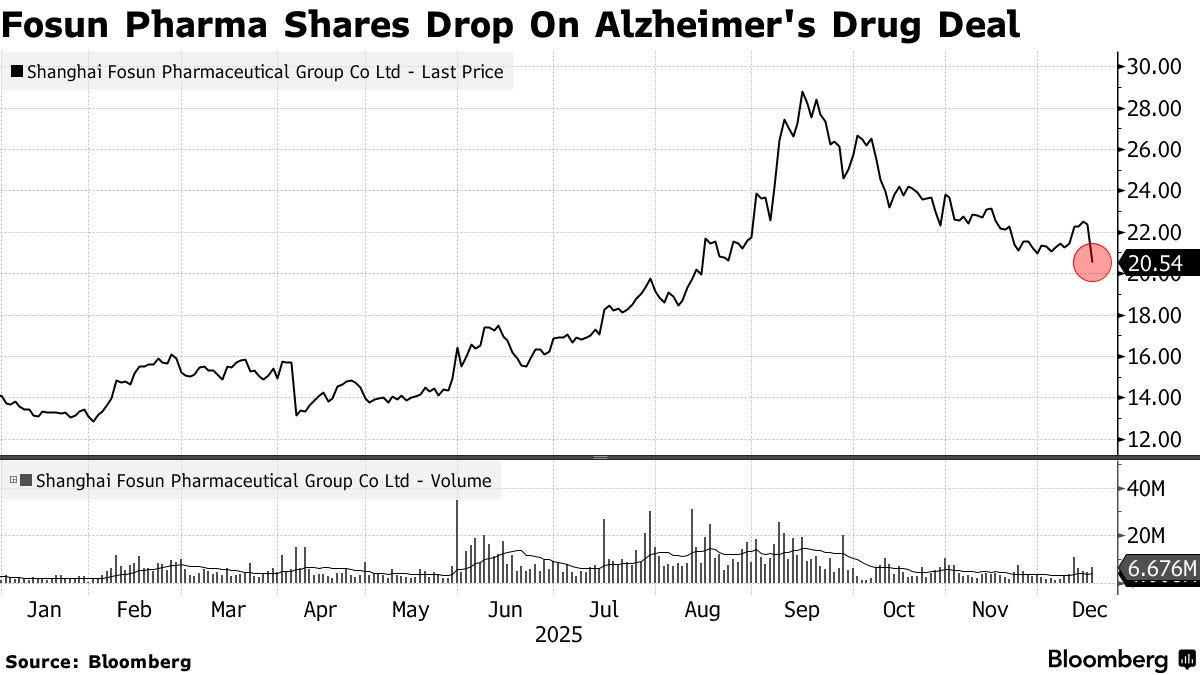

Fosun Pharmaceutical (600196.SH, 02196.HK) said on December 15 it plans to acquire a controlling stake in Green Valley Technology, the Chinese developer of sodium oligomannate (GV-971)—a drug that the company has long promoted as China’s first homegrown treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Fosun has also added that it would restart halted trials and, eventually, return the product to the market.

The market’s initial reaction was swift: Fosun’s shares fell close to 10% after the announcement. As reported in English so far, that move is easy to read as a verdict on GV-971’s scientific and commercial uncertainty. But there is another, arguably more basic factor that deserves to be part of any investor’s “first read” of this deal: Green Valley’s reputation—built over decades—has been shaped not only by controversy around efficacy, but also by a long trail of publicly reported marketing and compliance scandals involving earlier “miracle drug” claims, regulatory actions, and exposés by major Chinese media outlets, including state media.

International coverage has every right to focus on what is new: Fosun Pharma’s strategy, the status of trials, and the regulatory pathway.

Still, what’s striking is how little of that long-running public record has appeared in mainstream international write-ups—including Bloomberg’s December news report, subsequent newsletter post, its June report, and even its 2019 initial report on GV-971—leaving the narrative largely anchored to corporate statements and forward-looking hopes.

Even if one brackets the debate over whether GV-971 ultimately works, the developer’s history matters as context for assessing reputational risk, regulatory scrutiny, and why markets may punish the acquirer. When that context goes unmentioned, many readers—and certainly many potential investors who are not well-versed in the Chinese mediasphere—are unlikely to know it exists at all. And that missing background may be central to understanding why Fosun Pharma’s bet triggered such an immediate selloff.

Green Valley’s “miracle drug” reputation did not begin with Alzheimer’s. Long before GV-971, the company’s earlier flagship products were promoted with sweeping anti-cancer claims that were later dismantled in public view—through repeated findings of illegal advertising and, ultimately, regulatory action. Chinese state media reported that “Shuangling Guben San” (formerly marketed as “China Lingzhi Bao”) appeared in national-level unlawful drug-advertising bulletins hundreds of times, an extraordinary record; reporting also documented cases of fabricated or misleading promotional materials, including the forgery of issues styled as state-run Health Times for distribution.

History matters because GV-971, too, has often been portrayed as unusually “magical”—not merely effective, but effective in almost every way. Neuroscientist Rao Yi, writing in Cell Research in an Editorial Board capacity, highlighted how earlier publications by the drug’s developers attributed to the drug a long list of disparate mechanisms and targets. Rao added: “I have never come across a single drug with so many targets for curing or alleviating one disease.”

As it happens, Green Valley Technology now also advertises “Research Findings on Sodium Oligomannate (GV-971) for Treating Severe Acute Pancreatitis Published in Nature Communications,” as if the scientific journal proves the drug now treats another disease.

When you really read the journal article, it reports GV-971 “as being a protective agent in various male mouse SAP models” - a long way from being a treatment for humans.

What follows is my attempt to provide some of that missing background—specifically, the reputational and regulatory context that has been widely discussed in Chinese public discourse for years but rarely surfaced in English-language coverage.

To do that, I’m translating an essay that has been circulating widely in China in recent days. Published initially on 星球商业评论 Planetary Business Review, an influential WeChat blog. It is written in a deliberately biting, satirical voice. That tone is not accidental: for many Chinese readers who have heard of Green Valley over the past few decades—if only in passing—it is difficult not to approach the company with deep skepticism shaped by its long-running public controversies. Some passages may feel a little hard to parse because the author leans heavily on irony and cultural shorthand, but you’ll get the idea.

It also strains credulity that Fosun Pharma’s stock disclosure made zero mention of Green Valley’s checkered past, which, by the way, is no excuse for Bloomberg’s reporting omission.

The exact legal entity that Fosun Pharma now takes over might not be the ones that were repeatedly disciplined by Chinese state regulators or shamed by Chinese state media. Still, they share the Green Valley brand and the same ultimate beneficial owner, along with other overlaps.

I was once admitted to but ultimately not enrolled in a top Chinese law school, but it doesn’t take a law degree to ask how those scandals could not be considered material information that must be disclosed by the Shanghai- and Hong Kong-listed company in this “disclosable transaction”?

——Zichen Wang

治不了阿尔兹海默还治不了你

Can’t Cure Alzheimer’s, But Can Sure “Fix” You

by 杨乃悟 Yang Naiwu

Today, I saw that Fosun Pharma is preparing to spend 1.4 billion yuan to acquire Green Valley, a company known for its “miracle drugs.” As an “old friend” of Green Valley, I feel compelled to say a few words.

Green Valley’s best-known product today is Sodium Oligomannate Capsules, also known as GV-971, but in reality, it has had plenty of other “miracle drugs.”

About 30 years ago, Green Valley bribed Zhao Sian, the then-Director of the Drug Administration Division of the Shaanxi Provincial Health Department, on two separate occasions. Through this, they obtained approval documents for five types of drugs, successfully transforming a health supplement called 中华灵芝宝 “China Lingzhi Bao” into a pharmaceutical product named 双灵固本散 “Shuangling Guben San.”

Unlike those who simply hire elderly actors to play “old Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) doctors” and make “decisions that violate their ancestor’ wishes” (claims that went against basic scientific principles), Green Valley recruited real experts. Ding Jian, then-Director of the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (SIMM) under the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and its Professor Chen Jinsheng, among others, lavished praise on Green Valley’s products, claiming that this drug could treat multiple types of cancer and kill various cancer cells.

The “unlawful drug advertisement announcement system” was established in July 2001. By the end of 2006—within just five years—“Shuangling Guben San” had been listed in the national-level Public Announcement on Unlawful Drug Advertisements a staggering:

Over 800 times.

In 2007, when then State Administration for Industry and Commerce (SAIC) reported to the General Office of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, it specifically mentioned Green Valley and its affiliated companies for being penalized multiple times by relevant authorities. In one year alone, the Shanghai industrial and commercial authorities investigated and closed 12 cases of illegal advertising regarding “Shuangling Guben San,” imposing fines totaling 890,000 yuan.

With such a long record of misconduct, is it possible that the experts didn’t know about it? What’s more, it’s no coincidence—these so‑called experts were either shareholders of Green Valley or executives of Green Valley.

The National Medical Products Administration did not officially withdraw this so‑called miracle drug until April 28, 2007. On that date, the NMPA revoked the approval of Shuangling Guben San, because “the clinical trial data were not authentic and the promotional content went beyond the approved scope of functions and indications.”

Did people think that the relevant authorities had defeated the evil?

LOL—Chinese hospitals were soon once again filled with Green Valley’s sales representatives. These people were already out there promoting a new “miracle drug”:

Green Valley Lingzhi Bao.

Not only were they marketing in hospitals, Green Valley employees even went so far as to fake various newspapers and magazines—for example, forging issues of Jiankang Shibao [an industry newspaper under the People’s Daily, the flagship newspaper of the Communist Party of China] and distributing them in some hospitals, pharmacies and on the streets in places like Wuhan and Zhengzhou.

False promotion and even forging state media weren’t enough to bring Green Valley down. It stubbornly survived to this day and will be acquired by Fosun Pharma for 1.412 billion yuan. According to Fosun Pharma’s public statements, the company still believes in the past of the drug known as “GV-971” for Alzheimer’s disease, and remains optimistic about its future.

So let’s first talk about the past of this drug. More than a decade ago, Green Valley’s founder, Lv Songtao, through an introduction from Ding Jian, met researcher Geng Meiyu, who also came from the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica.

Researcher Geng Meiyu and her team developed a drug for treating Alzheimer’s disease that caught Lv Songtao’s interest. According to Lv, he even borrowed 500,000 US dollars and signed an 80 million US dollar contract to secure the patent for the drug.

In 2019, GV‑971 received conditional approval from the National Medical Products Administration. This decision drew opposition from many experts, including Rao Yi, then president of Capital Medical University. Critics questioned the drug’s effectiveness, saying its benefits were not obvious and the trial periods were too short.

You may be medical experts, that’s true—but do you understand miracle drugs?

Amid a chorus of opposition, GV‑971 was conditionally approved for marketing. Last year, GV‑971 sold 2.3 million boxes with sales exceeding 600 million yuan, and it was even included in the national medical insurance reimbursement list.

By the end of last year (2024), the approval for GV‑971 had expired. According to the regulations, Green Valley needed to submit confirmatory clinical trial data to the National Medical Products Administration. “Confirmatory clinical trial data,” in one phrase, means:

randomized, double‑blind, multicenter.

I knew that traditional Chinese medicine couldn’t stand up to this, but who would have thought GV-971 would also be vulnerable? Because the data was not submitted, the so‑called miracle drug was pulled from production.

And that wasn’t all—Green Valley even tried to apply to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for a Phase III clinical trial, but in 2022 it also announced that this was being stopped. The reason given was:

there was no money.

Alzheimer’s disease drug research is a bottomless pit—major pharmaceutical companies around the world have poured in more than 600 billion US dollars, involving over 300 drug candidates, with a very high failure rate.

GV‑971 can sell more than 600 million yuan worth in a single year, but whether this drug actually works is a question that I don’t know—what we do know is that an effective medicine never runs out of money.

GV‑971 was discontinued, so what happened to the friends who stocked up on it back then?

The former director of the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Ding Jian, went on to found a company called Haihe Biopharma. In 2021, the company attempted a listing on China’s STAR Market (The Science and Technology Innovation Board) but failed to pass the review. The reason was that the STAR Market review committee questioned its R&D capabilities.

Researcher Geng Meiyu succeeded Ding Jian as director of the Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica and became a shareholder of Green Valley. This year, she also became a candidate for election as an Academician of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, and I found that her nominator was none other than:

Ding Jian.

So, ladies and gentlemen, they’ve truly reaped both fame and fortune.

Today’s Green Valley no longer sells any so‑called anticancer miracle drugs. If you visit Green Valley’s official website, you will see promotions about gut‑brain axis research, Alzheimer’s disease, care for the elderly population, and endorsements by well‑known expert teams for the effectiveness of GV‑971.

If GV‑971 is really so effective, don’t just say it on your own website—go tell the National Medical Products Administration!

So I’ ve noticed that the authorities have already taken note of Fosun Pharma’s acquisition of Green Valley—whether the deal goes through still depends on regulatory approval and the drug’s clinical data. But once the acquisition news broke, Fosun Pharma’s share price immediately dropped.

Don’t run off yet, folks—I checked Green Valley’s official website, and they’re already promoting GV‑971 for treating acute pancreatitis and inhibiting peripheral inflammation.

Here’s hoping this time you don’t just say “if it works, it works; if it doesn’t, whatever.”