From street strategists to establishment pundits

The ground has already moved before a (temporary?) ban of Lu Kewen.

China’s “world affairs fandom” is a curious subculture. It has grown in an information environment shaped by many forces at once: attention-driven platforms, uneven media literacy, and a speech market where red lines are sensed more often than spelt out, nudging participants towards euphemism and hint. Meanwhile, much of the global conversation sits behind a firewall, leaving a peculiarly domestic version of “the world” to circulate—one that rewards second-hand certainty more than first-hand knowledge.

From this ecosystem emerge the “street strategists” and their higher-end cousins: some shouting in big-font slogans for the mass market, others offering a more polished variant for lecture halls and conference rooms. Either way, the job is the same: boil the world down into something brutally simple and eerily conspiratorial.

And in that setting, moderation tends to be a liability. The loudest voices are not merely amplified by algorithms; they are often spared the swift correction that greets less convenient kinds of speech. With only selective braking by platforms and regulators (sometimes in the name of accuracy), the scene starts to seal itself off, until its internal feedback loop supplies all the coherence it needs. In-jokes become catchphrases; catchphrases harden into doctrine; doctrine turns into badges of belonging, and then into habits of feeling.

Soon, people are no longer arguing with the world so much as with one another, inside a closed loop of their own making. The talk turns self-referential; outrage is recycled, intensified, and taken as evidence. The result is a discourse complete with its own worldview, folklore, and language, shaped as much by self-imposed insularity as by official gatekeeping.

The recent (temporary?) ban of Lu Kewen, a mega-influencer of the “patriotic” persuasion, has triggered revealing reactions from within this stratified, closed ecosystem. Many cheered. Some, like Song Xi 宋晰, author of the first piece translated below, could not resist a little self-congratulation: Lu, they insisted, merely caters to the less educated; the white-collar set in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou would never fall for it. The implication was reassuring. The problem, in this telling, lives somewhere else: in factory dorms, in county-town internet cafés, not in Starbucks.

The second essay by Guang Buyu 关不羽, a freelance journalist, offers a sharp correction. True, the mass version shouts. But the “premium” version isn’t an antidote—it just speaks more softly and dresses itself up with a preamble: Anglo-Saxon blocs, Jewish conspiracy, Freemasons as a kind of intellectual foreplay, sold as sophistication. Different tiers, same closed loop.

Both pieces are translated below as field notes from an ecosystem in China for talking about international politics.

The first essay was published on Song Xi’s personal WeChat blog on 8 December, and the second on Guang Buyu’s personal WeChat blog on 9 December.

—Yuxuan Jia

The influence of “street strategists” is widely underestimated. As their style of commentary steadily occupies more of China’s opinion market—and as similar figures do the same across many countries, for all sorts of reasons—something dangerous happens. As the trend continues and intensifies, it is only a matter of time before what the “elite” once mocked as obvious nonsense becomes the mainstream’s working vocabulary for understanding the world, and from there it starts to steer agendas, bend judgments, and nudge policy in ways that feel “natural” only because the ground has already moved.

—Zichen Wang

卢克文工作室被封:一个“地摊战略家”的破产

Lu Kewen Studio Shut Down: The Bankruptcy of a “Street Strategist”

By Song Xi

Lu Kewen Studio’s WeChat blog no longer shows up in search results. It’s like the corner hotpot stall, always boasting about its “secret recipe,” finally getting shut down by the authorities.

The reason given is the standard wording: “This account is suspected of violating regulations, and its ability to open web pages from the WeChat official blog has been restricted.”

Its last article was titled “China Is Preparing For War Against Japan”. The headline sounds like a battle cry, making this provincial small-town guy seem like he’s got some inside scoop.

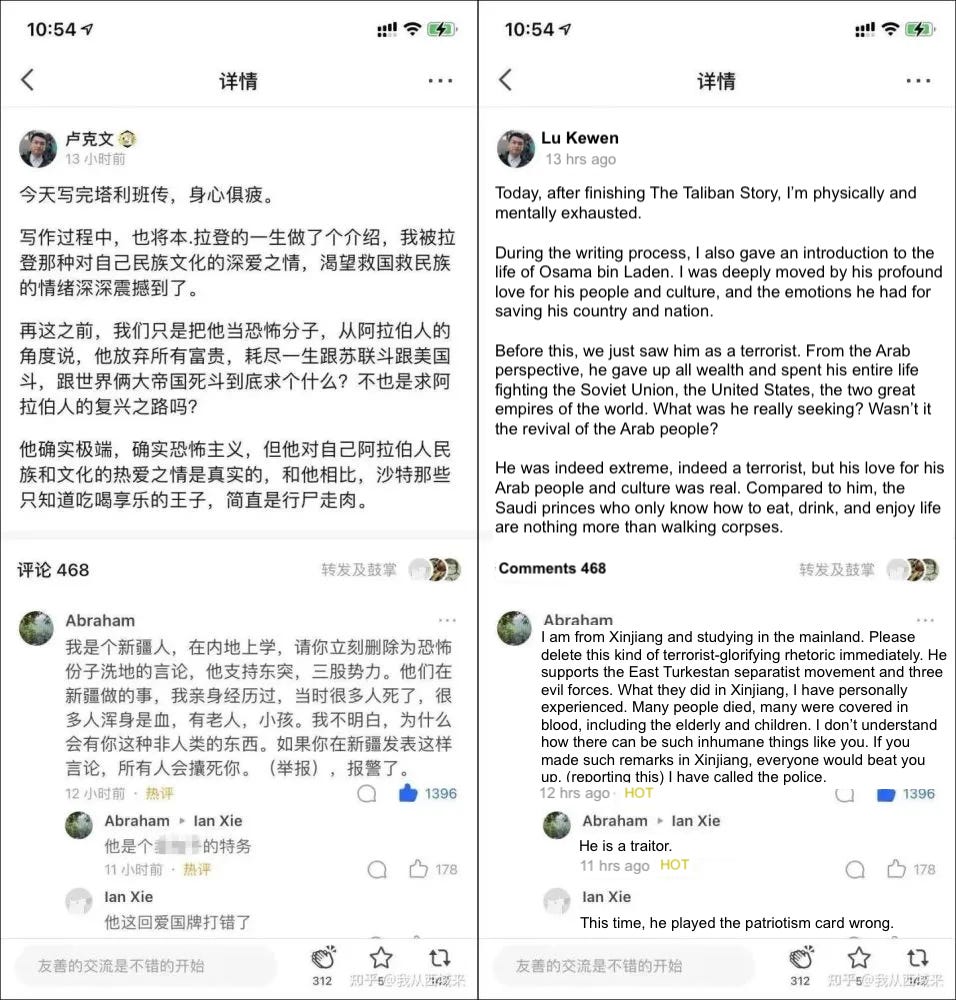

This isn’t Lu Kewen’s first time being “suspended for rectification.” Back in 2021, his piece The Taliban Story was full of a “deep awe” for Osama bin Laden, like a naïve, overly romantic youth. It freaked out internet users in Xinjiang, who rushed to post, “Please delete this terrorist-glorifying content; I’ve seen what they do.”

On that occasion, his Zhihu [China’s equivalent of Quora] account was muted, and his WeChat blog shut down.

1

The rise of Lu Kewen is a classic example of the social media era. In 2018, he transitioned from being an e-commerce manager to styling himself as an “observer of international affairs.” In 2019, an article titled Moon Jae In’s Revenge brought in 300,000 new followers, and from then on, he was on the fast track to becoming a political news influencer.

His formula is simple: he stews complicated international politics into a spicy hotpot, adds plenty of chilli, cuts back on the facts, and tops it off with a dash of “profound changes unseen in a century.”

Uneducated readers are loving it, sweating buckets and screaming for more.

This “strategist,” a graduate of Hunan Polytechnic of Water Resources and Electric Power, has created a string of social media spectacles. Take his Japan-election call: in the morning, he confidently declared that Shigeru Ishiba “would never be elected in his lifetime,” only to be humiliated by reality in the afternoon. The next day, he conveniently pinned it on a “low-key younger colleague” in his studio—and netizens had a field day, noting that even the scapegoat has more integrity than he did.

When he wrote about the U.S.-Japan trade war, Zhihu users uncovered that he had lifted material from fifteen articles. He replied calmly that “consulting sources is not plagiarism”.

In his analysis of the U.S. Navy, he slapped on a photo from the Dalian shipyard in China. When called out, he explained that this was “deliberate satire”. It’s the kind of unrepentant stubbornness that could point at a panda and swear it’s a polar bear, and, frankly, there’s nothing anyone can do about it.

But la pièce de résistance? The Taliban Story. A group that’s been responsible for bloodshed in Xinjiang is suddenly portrayed as having a “sense of saving the country and the nation.” It’s like praising an arsonist for having “artistic flair” in their fire-starting technique.

Even his apology was a textbook case. He first said that he “had not expressed himself clearly”, then accused a so-called “anti-homeland camp” of smearing him.

Lu Kewen has truly mastered the art of the “mistake + victimhood” combo.

2

But here is the question: How does a social media outlet that makes poor predictions, often gets facts wrong, and frequently strays off course in its values manage to attract thirty million followers?

The answer lies in the internet cafes of county towns and factory dormitories across China. While white-collar workers in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou debate “geopolitical structures” over coffee in Starbucks, young people from small towns are scrolling through Lu Kewen’s short videos, claiming to “reveal the truth about the world,” during their assembly line breaks.

They don’t have time to read Foreign Affairs, but they sure know how to digest headlines like “The United States Is Finished” or “Japan Is Doomed.” They can’t tell the Taliban from Tajiks, but they can remember slogans like “The West will never stop trying to bring China down.”

Lu Kewen’s success reveals a gaping hole in the knowledge base of Chinese internet users. While scholars from formal education systems are still clinging to terms like “structural contradictions” and “non-traditional security,” Lu Kewen and his ilk are dominating billions of phone screens with language more at home in a mahjong parlour—“Great power rivalry is like playing mahjong,” “The U.S. is the dealer.”

This isn’t a triumph of knowledge. It’s a triumph of knowledge simplified and weaponised to overpower everything else.

China’s internet users are like a big, mixed stew. You’ve got the top students from prestigious universities, and you’ve got workers who dropped out of school in junior high. Some can quote Francis Fukuyama and Samuel Huntington, while others think the Taliban are heroes.

Lu Kewen has perfectly hit the sweet spot: he’s zeroed in on those hungry for world knowledge but lacking the ability to critically assess it. What he serves up isn’t vitamins—it’s sugar, chilli, and a quick hit of dopamine that excites people instantly.

When it comes to international politics, he immediately morphs into a “street strategist,” transforming complex geopolitics into a wuxia novel: The United States is the evil cult, and Japan is the traitor who’s joined forces with it.

Readers get swept up, feeling their blood race, as if they aren’t factory workers earning four thousand yuan a month, but grand strategists plotting behind the scenes.

3

This ban is likely temporary. Just like every previous “suspension,” he’ll probably just rebrand and get back to business.

The market is still there. The demand is still there. Young people doing repetitive work on assembly lines still crave a crude, simple “user manual for the world.” Elderly men whiling away their afternoons in small-town teahouses still love to hear the storyteller’s dramatic punchline that “China and the U.S. are destined for war.”

Lu Kewen won’t disappear, much like how “gutter oil” hasn’t yet disappeared from night markets. As long as people refuse to digest real knowledge, there will always be someone willing to process information into baby food and spoon-feed it to them. The sad truth is that in this age of the attention economy, it’s often the slop flavoured with “the deep sentiment of Osama bin Laden” that brings in the big bucks.

When the ban notice for Lu Kewen Studio quietly appears, somewhere on the other side of China’s internet, a new “Studio X” is likely already in the works. These creators have cracked the formula: simplify complex issues, turn historical figures into pop idols, and turn international relations into a xuxia novel. That’s the traffic code. Tens of millions of fans are eagerly waiting for the next “street storyteller” to explain this world they know yet don’t fully understand, using language they can grasp.

In this age of information overload and scarce wisdom, mocking Lu Kewen is easy, but the truth is hard to deny: he’s just a mirror reflecting the distorted market demand. The mirror reflects not only that “small-town strategist” from Shaoyang, but also the hundreds of millions of ordinary Chinese people who long to understand the world but are unable to grasp its complexities.

When legitimate knowledge remains high up in its ivory tower or can’t be spoken for “special reasons,” there will always be “knowledge peddlers” opening fast-food stands in the corners, selling instant noodles spiced up with sensational seasoning. And the customers will line up, devouring it with pleasure.

爱看卢克文的,可不止小镇青年!

It Is Not Just Small-Town Youth Who Love Lu Kewen!

by Guan Buyu

Lu Kewen, the “patriotic influencer,” has been banned again, and it’s caused quite a splash. A WeChat blog titled “Lu Kewen Studio Shut Down: The Bankruptcy of a ‘Street Strategist’” is making the rounds in group chats; it is sharp, cutting, and genuinely worth reading.

It raises a question that’s hard to ignore: “How does a social media outlet that makes poor predictions, often gets facts wrong, and frequently strays off course in its values manage to attract thirty million followers?”

The author answers himself: “The answer lies in the internet cafes of county towns and factory dormitories across China. While white-collar workers in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou debate ‘geopolitical structures’ over coffee in Starbucks, young people from small towns are scrolling through Lu Kewen’s short videos, claiming to ‘reveal the truth about the world,’ during their assembly line breaks.”

That’s a bit too neat.

01

The market for “street strategists” is layered, too.

At the very bottom are the big-font posts made grandpas only, the kind of thing that fuels park small talk during morning exercises, or kills time on those soul-sucking long trips on hard seats. Outside the old men’s circle, nobody’s reading it.

At the top, you have the “establishment” tier, the Jin Canrong-type figures with their permanently blooming smiles, playing in the high-end venues. They do the university lecture-hall circuit and the enterprise-and-government conference-room circuit. A single “guest lecture” can easily run into the six figures, and the audience is very much educated.

Lu Kewen sits somewhere in the middle, not bottom-shelf, not quite ivory tower either. Last December, he rolled out a “Life Upgrade Course” on one platform, priced at 199 yuan and marketed on the idea of “contentment economics.” It was pure middle-aged self-help platitudes. It pulled in 500,000 subscribers and topped the annual rankings. By topic and by price, that was never aimed at “internet cafes of county towns” or “factory dormitories.”

He’s tried going downmarket, too. In August 2022, he did his Douyin livestream e-commerce debut and sold only 600 yuan’s worth in an hour, becoming a laughingstock in the industry.

Not hard to see why. Lu Kewen’s signature move is the sprawling mega-essay, casually running into the thousands, even tens of thousands, of characters. That does not exactly fit into “internet cafes of county towns” or “factory dormitories.” Downmarket users often can’t be bothered to finish even 3,000 words. They are more receptive to the ranting performances of Sima Nan [His nickname “Head-Wedge” is a piece of internet folklore: during Lunar New Year in 2012, after railing on Weibo against “American universal values,” he flew to the U.S. to reunite with his family and reportedly got his head stuck in the gap in an escalator at Washington Dulles International Airport]: maximum emotional payoff, minimum interest in Lu’s cobbled-together, puffed-up “knowledge increment.”

In reality, the whole image of “white-collar workers in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou debating ‘geopolitical structures’ over coffee in Starbucks” isn’t all that impressive. The underlying logic and the value system are not fundamentally different from the teahouse uncles, the county-town internet cafés, or the factory dorms. It’s the same mix: long-term anti-Americanism, periodic anti-Japan flare-ups, and “win-ology” [a Chinese internet meme that riffs on “everything is a win” rhetoric] paired with “grand chessboard” narratives, all marching in formation. After a few rounds of baijiu, someone will inevitably slam the table and announce, with vehement conviction, that “China and the U.S. are destined for war,” or “China and Japan are destined for war.” The only upgrade in the so-called “high-end game” is the foreplay: you don’t just get “destined for war,” you get the Anglo-Saxons, the Jews, and the Freemasons as the opening act. That preamble is exactly what Lu Kewen and his kind are selling.

Lu’s thousand-word, mystical-sounding essays shore up a cosy club mentality, while handing the better-off a smug little badge of class superiority: “We are above ordinary people.” With a product like that, his success isn’t exactly a mystery, is it?

02

Chinese intellectuals tend to dodge one uncomfortable point: that club mentality cuts across class lines. The highly educated and the illiterate aren’t that different when it comes to judgment. A diploma isn’t knowledge, and knowledge isn’t judgment. How much real knowledge a degree contains depends on what schools actually teach. Whether knowledge turns into judgment depends on the courage to think. Do Chinese intellectuals have that courage?

Most Chinese people pass through two stages. In school, it’s “learning without thinking”: whatever the textbook says goes, and nobody dares step over the line. Once they enter society, it becomes “thinking without learning”: they stop reading altogether but develop a strong hobby for free-associating. So, however impressive the credentials look, a lot of people still think on instinct. The worldview of a star university graduate can end up looking eerily similar to that of a worker who dropped out of junior high. And the Fukuyama and Huntington quotes are often not engaging the ideas at all, just renting authority to legitimise a pre-cooked take.

This impregnable club mentality is exactly what leaves so much room for “street strategists.” Anyone who can repackage the same old instincts can carve out a niche audience. The real edge in this business isn’t insight. It’s audacity: taking the latest news, forcing it into a familiar script, then selling the result as a new product. The packaging may be grubby. The demand is steady.

For example, that “Anglo-Saxon bloc” line so many elites love to drop is actually lifted from Japanese militarist ideology, and it slots right into anti-Western ranting. The anti-Semitism that made Lu Kewen famous is a direct inheritance from Nazi racial thinking. The “analysis” is easier still. Just loot the Ming–Qing historical romances—Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Chronicles of the Eastern Zhou Kingdoms, the full Thirty-Six Stratagems starter kit. And for “values”? The nineteenth-century worldview of grabbing money, land, and resources still does the job.

Every “street strategist” runs some version of this formula. The main difference is presentation: they season the same dish to match the customer. For the less-educated, it’s the blunt stuff, “might makes right.” For the better-off crowd, it has to sound more refined: “truth lies only within the range of the cannon,” ideally misattributed to Otto von Bismarck for that premium, imported vibe. And honestly, it’s a safe scam. Once people get their credentials, they stop reading anyway, so nobody’s going to call the bluff.

03

The gap between “street strategists” and certain so-called “establishment” strategists is basically just a robe. With the robe, you’re a court chaplain. Without it, you’re a backwoods preacher with a loyal flock and a little fiefdom of your own.

Different niche, same scripture. Lu Kewen is shameless enough to crib from the Nazis. But a certain major tabloid-turned-mainstream newspaper has pulled the same stunt—running a Joseph Goebbels quote as a headline. Lu makes things up; a certain editor-in-chief also built a reputation on the “Defence of Baghdad.” “Making poor predictions, often getting facts wrong, and frequently straying off course in its values” isn’t Lu’s personal trademark.

So what if Lu gets banned? The ecosystem stays the same, and it never runs out of replacements, because China’s middle-class elites need these “street strategists” to feed their self-destructive craving.

These “street strategists” cash the peace dividend without valuing peace. They rose in the age of globalisation, yet still crave the “toughness” of picking fights with the whole world. Status without a matching judgment ends badly. And with demand like that, one less Lu Kewen doesn’t change much.