Guan Tao on the yuan's exchange rate as an asset price

Former State Administration of Foreign Exchange Director-General on the Chinese currency's overshooting and multiple equilibriums, the 2015 exchange reform, etc.

Renminbi, or the yuan, swung 13% in just eight months of 2022 with its largest midpoint fluctuation over the past two decades reaching 15.1%. The 6.3-to-7.3 drop against the U.S. dollar happened while China ran a record-high trade surplus of $877.8 billion. At the end of 2022, China reported dismal economic data but the yuan climbed from 7.3 to 6.7 in three months starting November 2022. Why?

According to Guan Tao, Chief Economist with Bank of China International Holdings Co., Ltd (BOCI) Securities Limited and former Director-General of the Balance of Payments Department of State Administration of Foreign Exchange (2009-2015), the Chinese currency’s exchange rate is increasingly showing the property of an asset price after the August 11, 2015 - known in China as “8.11” - reform.

I should have presented the highly technical videotaped lecture, 推动中国高水平开放的几个理论与实践问题 Several Theoretical and Practical Issues on Promoting China’s High-Level Opening-Up, much earlier as Guan recorded it on March 30, 2023 at Tsinghua University.

Guan also dispelled some misunderstandings in the talk. He said there was no “foreign divestment from dollar assets” in 2022 and that the yuan’s depreciation didn’t drag down the Chinese stock market. He also visibly defended the “8.11” - reform, saying it paved the way for China’s central bank to withdraw from regular interventions. The increased flexibility of the yuan’s exchange rate and the significant improvement in marketization effectively supported China's push for institutional openinng, he added.

Below is only Part One - centering on the yuan’s rate - of his three-part speech. Please note again the talk was given in 2023, so all those “last year” refers to 2022.

China's decision to open its doors for construction starkly contrasts with the current global trend of moving away from globalization, leaving many feeling bewildered. Historically, the post-war global economic governance system was established under the leadership, or perhaps dominance, of the United States. However, it is now China that is vocally advocating for opening up and engaging in construction. Meanwhile, the United States seems to be moving in the opposite direction, pursuing policies of decoupling, breaking industrial chains, and adopting a "small yard, high fence" approach. This rapid change has led many to feel that we are living in a time of accelerated historical shifts.

Today, I will delve into three key topics. The first concerns the Renminbi's exchange rate. Last year, the Renminbi underwent a significant adjustment, appreciating at the start of the year but then experiencing a sharp rise and subsequent fall from 6.3 to 7.3 by early November 2022, all within just 8 months. Despite achieving a historic trade surplus of $877.8 billion, the Renminbi depreciated. This raises questions about our understanding of the Renminbi's current exchange rate adjustment and whether it should be considered commodity money or an asset price. By applying theoretical concepts to real-world issues, we can grasp the nature of these economic phenomena.

The second topic of discussion is the internationalization of the Renminbi, which has recently been a subject of considerable interest. Today (On March 30, 2023), it was reported that China and Brazil have signed an agreement to encourage pricing and settling trade between the two countries in their respective currencies, thus bypassing the US dollar. Similarly, an agreement was reportedly signed between Saudi Arabia and China for the sale of some oil to China, priced and settled in Renminbi. These developments are integral to the ongoing process of Renminbi internationalization.

The 20th National Congress of the Communist Party of China's work report references Renminbi internationalization, advocating for its orderly advancement. This raises questions about the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead for Renminbi internationalization, how to further promote it, and why some countries maintain a cautious stance towards their currency's internationalization, in contrast to China's active promotion. What underpins this strategy?

The third issue revolves around the enigmatic trillion-dollar surplus discrepancy. This topic has sparked considerable discussion, especially in light of last year's nearly $900 billion trade surplus coinciding with a $122.5 billion decrease in foreign exchange reserves. The question arises: why did a substantial trade surplus result in a significant reduction in foreign exchange reserves, and where did the surplus in excess of $1 trillion disappear to? This issue also touches on the domestic challenges of demand contraction, supply shock, and weakening expectations, highlighting concerns about the discrepancy between trade balance and foreign exchange reserve changes. Our approach is to address these questions with data, offering explanations and clarifications.

Turning to the Renminbi exchange rate, last year witnessed a notable adjustment, with the rate shifting from 6.3 to 7.3 within eight months, a change exceeding 13%. This contrasted with the period from April 2018 to May 2020, when the Renminbi depreciated from 6.28 to 7.2 over 26 months. The recent adjustment period saw the Renminbi's volatility significantly increase, with the largest midpoint fluctuation over the past two decades reaching 15.1%. A prevailing market question is why the Renminbi depreciated despite an expanding trade surplus. To understand this, we must look beyond traditional views of commodity money and recognize that, as China's economy becomes more market-oriented and globalized, the Renminbi exchange rate increasingly exhibits the characteristics of an asset price.

This perspective is grounded in the August 11 2015 Renminbi exchange rate reform, aimed at enhancing market orientation. The early phase of this reform saw a cycle of capital outflow, reserve depletion, and currency depreciation, prompting significant central bank intervention. However, post-2017, the Renminbi exchange rate has stabilized, entering a new phase of bidirectional fluctuation. Since then, the central bank has largely ceased regular interventions in the foreign exchange market, leading to a shift in China's international payments from concurrent surpluses in both current and capital accounts to a pattern of one surplus and one deficit—specifically, a current account surplus paired with a net outflow under the capital account.

If you've studied international finance, you're familiar with the concept of the international balance of payments. You know that, in the absence of central bank intervention, the current account and capital account in the balance of payments act as mirror images of each other. That is, if one records a surplus, the other must show a deficit, and vice versa. Furthermore, a larger current account surplus correlates with greater net outflows in the capital account, as the sum of two positives or two negatives cannot equal zero.

The dynamic between the United States and China, however, presents a contrasting scenario. China maintains a long-term trade-based current account surplus alongside a capital account deficit, while the United States experiences a trade-based current account deficit paired with a capital account surplus. This discrepancy introduces complications in the international balance of payments, where trade deficits cannot straightforwardly explain or predict the depreciation of the U.S. dollar, nor can capital inflows solely account for its appreciation.

The same principle applies to China. In instances where a surplus and a deficit in the current and capital accounts offset each other, we cannot directly use the trade surplus to forecast the appreciation of the Renminbi, nor the capital account deficit to anticipate its depreciation.

Last year, our trade surplus expanded, leading to a current account surplus of $417.5 billion, marking a 32% increase from the year before. Concurrently, we noted the Renminbi's depreciation in the face of an expanding current account surplus, a phenomenon attributable to capital outflows. China's capital account deficit escalated to $317.6 billion last year, a 1.46-fold increase from 2021. Conversely, the United States experienced an expanding trade deficit and heightened capital inflows, yet the dollar appreciated, primarily due to these inflows.

Despite widespread speculation about foreign divestment from dollar assets, that was not the case and the speculation is, to a large extent, confusing stock and flow. The perceived "foreign divestment of dollar assets" can be largely attributed to the rise in US bond yields, a decline in bond prices, and a reduction in the stock of US Treasury bonds held by foreigners. Nonetheless, according to the US Treasury Department, net international capital inflow into the US reached a historic high of $1.61 trillion last year, a 45% increase from 2021, with private investors acquiring $1.68 trillion in net dollar assets, while official investors, including central banks, sold $70.1 billion.

This scenario illustrates that the dollar's appreciation in the face of an expanding US trade deficit resulted from capital inflows, while the Renminbi's depreciation amid a growing Chinese trade surplus was due to capital outflows. Therefore, we must abandon traditional interpretations of the Renminbi exchange rate, which directly correlate trade balance changes with the currency's valuation trends.

We emphasize this because if the exchange rate is viewed as an asset price, it exhibits two notable characteristics: exchange rate overshooting and multiple equilibriums. Overshooting means the market exchange rate can significantly exceed or fall below what is deemed the equilibrium rate. While China strives for the Renminbi's basic stability at a reasonable and balanced level, the market rate will inevitably fluctuate around this equilibrium due to its asset price characteristics.

Multiple equilibriums refer to the scenario where, given certain fundamentals, the market exchange rate could either appreciate or depreciate. Common assumptions suggest a trade surplus should lead to currency appreciation. However, the foreign exchange market's complexity means the impact of a trade surplus on the currency value depends entirely on market perceptions of the surplus's reasons. For example, if the market views a trade surplus expansion as indicative of weak domestic demand, the currency may face increased depreciation pressure, illustrating the concept of multiple equilibriums.

This phenomenon is not unique to China but is observed internationally. Everyone knows that Japan implemented quantitative and qualitative monetary easing in 2012, and it is generally believed that monetary easing leads to currency depreciation. Indeed, when the Bank of Japan implemented quantitative and qualitative easing in 2012, interest rate differentials drove the depreciation of the yen. However, when the Bank of Japan introduced a negative interest rate policy in 2016 to further ease monetary policy, the yen exchange rate should have depreciated further against the dollar. Contrarily, driven by risk aversion sentiment, the yen appreciated. Thus, even though it's the same monetary easing, its impact on the exchange rate varies under different circumstances, because at any given time, many factors can influence the exchange rate, and different factors play a major role at different times. In 2012, it was primarily interest rate differentials that influenced the trend of the yen exchange rate, but by 2016, it was not interest rate differentials, but rather risk aversion sentiment. This is what is called multiple equilibriums.

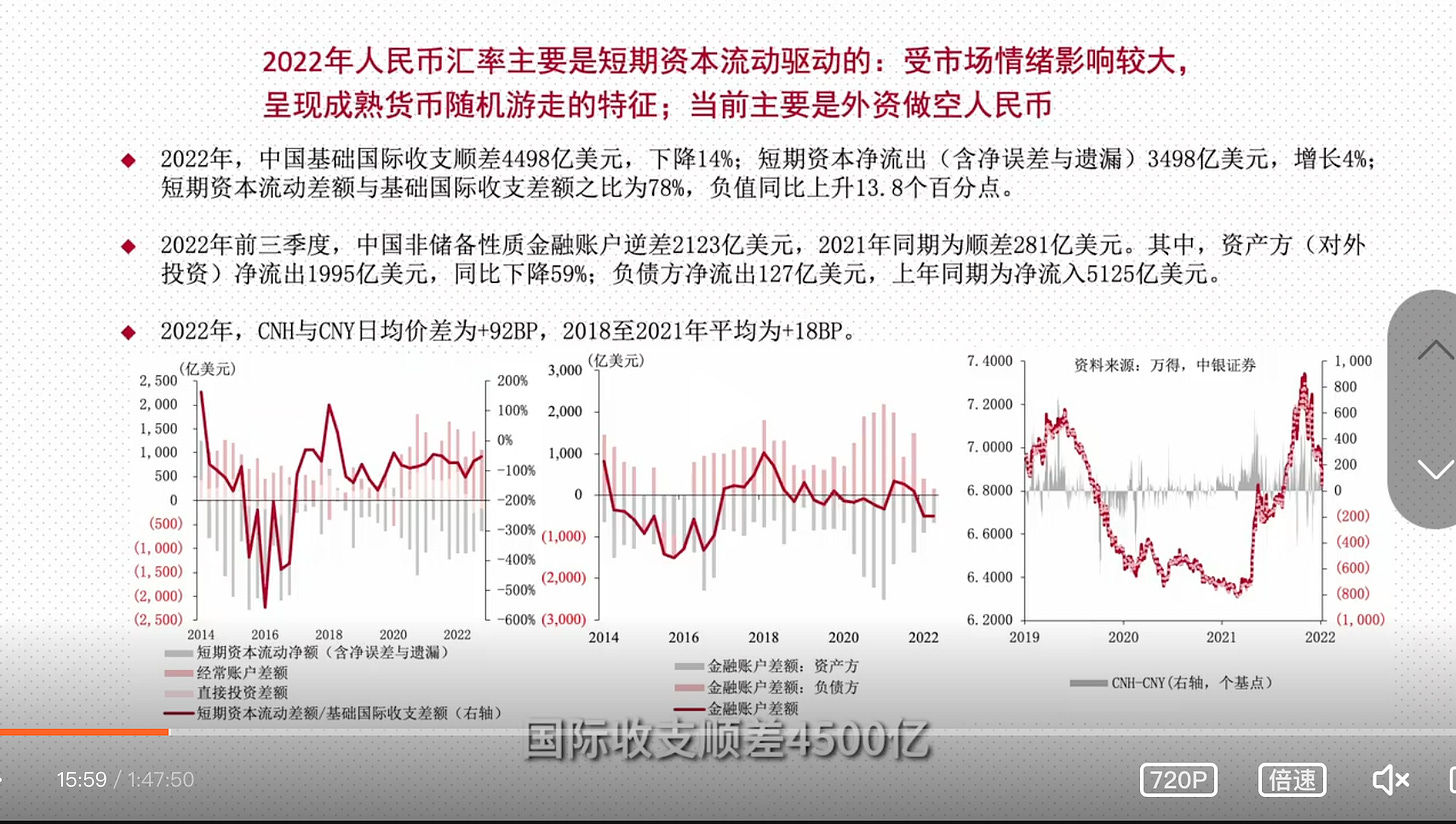

Last year's adjustment in the Renminbi exchange rate is a case in point of multiple equilibriums at play. Data shows that China's basic international payments surplus (the sum of the current account and direct investment) was around $450 billion, a decrease from the previous year. Meanwhile, short-term capital outflows increased by 4% to a net $350 billion, making the ratio of short-term capital net outflow to the basic international payments surplus 78%, an increase of 13.8 percentage points from the previous year. This indicates heightened pressure from short-term capital outflows last year. Short-term capital has a very important characteristic: it is easily influenced by market sentiment and not entirely driven by fundamentals. Therefore, the Renminbi exhibits characteristics of a random walk, similar to that of mature currencies.

The most typical is the end of last year, China was on the verge of breaking out of COVID-19 and had weak economic data, but this did not affect the Renminbi exchange rate’s rebound after November, from the beginning of November's 7.3 to 6.7 at the beginning of this year's - a rebound of about 9% in less than 3 months. At that time, our economic data was relatively poor, with many data showing negative growth, but this did not affect the Renminbi exchange rate rebound.

Why? On the one hand, in the overseas market, US inflation fell and the expectation for further tightening by the Federal Reserve eased, the US dollar and US bond yields fell, the US stock market rebounded, and market risk appetite improved. On the other hand, domestically, since November last year, optimized COVID-19 prevention and control measures and adjusted real estate policies improved market expectations for China's economic recovery prospects. So although the economic data was poor, because market expectations improved, the Renminbi still appreciated. In the last two months of last year, China's trade surplus fell year-on-year, but because the Renminbi exchange rate is an asset price, it did not affect the Renminbi exchange rate rebound.

Moreover, we can also use international payment data to find out whether the pressure of the Renminbi exchange rate adjustment comes from domestic or foreign, from the onshore market or the offshore market.

Last year, in the first three quarters, China's non-reserve financial account deficit was $212.3 billion, while the same period in 2021 was a surplus of $28.1 billion. Among them, on the asset side, that is, net outflows of foreign investment were $199.5 billion, a decrease of 59% year-on-year; on the liability side, that is, net outflows of foreign investment were $12.7 billion, while the same period in 2021 saw net inflows of $512.5 billion.

This indicates that China's net capital outflow under the capital account operates through two main channels: firstly, on the asset side, there has been an increase in the use of overseas assets, signifying active foreign investment. Secondly, the change in circumstances has led to a reduction in net inflows of foreign capital, which previously entered China, and these inflows have now been reduced or even turned into net outflows. In 2022, our foreign investment declined compared to the previous year, and the inflow of foreign investment into China shifted from a substantial net influx to a net outflow. Clearly, the pressure on last year's Renminbi exchange rate adjustment stemmed from the liability side, namely the decrease in foreign investment, rather than an increase in our foreign investment.

The onshore and offshore exchange rates further corroborate this point. Throughout last year, the spread between CNH (offshore Renminbi exchange rate) and CNY (onshore Renminbi exchange rate) was +92 basis points, indicating a tendency for the CNH to depreciate relative to the CNY.

Is this situation different from what we experienced in 2015 and 2016? The 8.11 [August 11, 2015] exchange reform triggered market panic, causing both domestic and foreign capital to flee. However, after the second quarter of 2016, foreign capital resumed net inflows, while domestic capital continued to flee. As I mentioned in a 2016 article, stabilizing the exchange rate is key to stabilizing the onshore market, including maintaining the confidence of domestic enterprises and households in the Renminbi. This time, however, the situation is different. The onshore market did not panic in response to the large fluctuations in the Renminbi, but foreign capital shifted from a significant net inflow in the previous period to a minor net outflow for various reasons.

We can also confirm this using high-frequency data. There's a common misconception in the market that equates the depreciation of the Renminbi with high depreciation pressure or expectations, suggesting that if the Renminbi depreciates, it indicates strong depreciation pressure and expectations. This is incorrect. Why? A crucial goal of the Renminbi exchange rate reform was to make the exchange rate formation increasingly market-oriented, allowing the market to play a greater role in determining the exchange rate.

What defines a normal foreign exchange market? In such a market, the [participants’\ principle is to buy low and sell high; that is, to buy more foreign exchange when the currency appreciates and sell more when it depreciates. At the end of 2016, when the Renminbi approached 7, there was a rush to purchase and hoard foreign exchange, indicating a malfunction in the foreign exchange market, not its normal state. However, many still do not understand that increased flexibility in the exchange rate helps release market pressure timely and prevents the accumulation of unilateral expectations.

Not everyone may deal directly with foreign exchange, but I know that many parents, because their children study abroad, need to purchase foreign exchange annually to pay for tuition fees. They wait for the Renminbi to appreciate further before buying. After an adjustment [fall] in the Renminbi's value, they delay purchasing, hoping for the currency to appreciate again before buying. For instance, last year, when the Renminbi exchange rate neared 6.3, many wanted to wait for it to reach 6.2 before buying. When it dropped below 6.4, they abandoned waiting for 6.2, hoping it would return to 6.3, but were surprised when it fell to 6.5, then to 6.7, and eventually to 7, at which point everyone hesitated to buy. This behavior reflects a normal foreign exchange market, where there's more selling of foreign exchange when the Renminbi depreciates and more buying when it appreciates.

What was the situation last year? Despite a significant depreciation in the Renminbi exchange rate, the domestic supply and demand for foreign exchange were essentially balanced, with a total surplus of $77.1 billion for the year, indeed less than the $200 billion surplus in 2020 and 2021. However, pursuing a larger surplus is not our goal; even a small deficit is acceptable.

Last year, the Renminbi's exchange rate moved from 6.3 to 7.3, but there was only a small deficit in foreign exchange settlement and sales for four months, with an average deficit of just $4.2 billion. Importantly, during the Renminbi's depreciation period, the willingness to settle foreign exchange generally exceeded the period of appreciation, and the motivation to buy foreign exchange was weaker than during appreciation, indicating that the foreign exchange market operated normally.

During last year's autumn annual meeting, the International Monetary Fund discussed exchange rate policy, suggesting that countries should maintain exchange rate flexibility to adapt to the cyclical differences in monetary policy across countries. It was also proposed that central banks should only intervene when changes in the exchange rate affect the transmission of monetary policy or pose substantial risks to financial stability. In simpler terms, with flexible exchange rates, the central bank should benignly overlook short-term fluctuations, intervening only when those fluctuations threaten price stability and financial stability.

Although the Renminbi's exchange rate experienced wide fluctuations last year, the foreign exchange supply and demand remained balanced, with the "buy low, sell high" principle effectively adjusting exchange rate leverage. This is a major reason the central bank remained relatively calm about the fluctuations in the foreign exchange market last year. Decision-making was not impulsive; instead, the focus was on data, monitoring the market daily. Currently, we use monthly data, but regulatory authorities have access to daily buying and selling data in the foreign exchange market, providing insight into the supply and demand situation.

The international foreign exchange market is typically invisible, but when we established the interbank foreign exchange market, we started from a visible market. The trading system of the 中国外汇交易中心 China Foreign Exchange Trade System at that time borrowed the experience of the stock exchange, with spot trading, centralized quoting, and clearing, allowing the central bank to understand the market's buying and selling situation timely. However, as the exchange rate formation became more market-oriented, our visible market gradually became invisible. We have both 撮合交易 price-matching transactions and 询价交易 over-the-counter (OTC) transactions, with the proportion of OTC transactions increasing. Nevertheless, banks are still required to report their trading activities to the China Foreign Exchange Trade System daily.

After the 2008 financial crisis, there was significant reflection on the crisis. A key conclusion was that as markets became more open and free, regulatory authorities failed to capture a lot of trading data timely. In some extreme market conditions, information asymmetry led to market panic. Thus, one important aspect of the reform of the international financial system post-2008 was to bridge the data gap, with many financial infrastructures establishing data reporting center systems. The China Foreign Exchange Trade System was ahead of the international trend in terms of foreign exchange trading reporting, whether transactions are OTC or price-matched, on-site or off-site, they must be reported. Global foreign exchange trading relies on the BIS’s Triennial Central Bank Survey, while we have access to daily data.

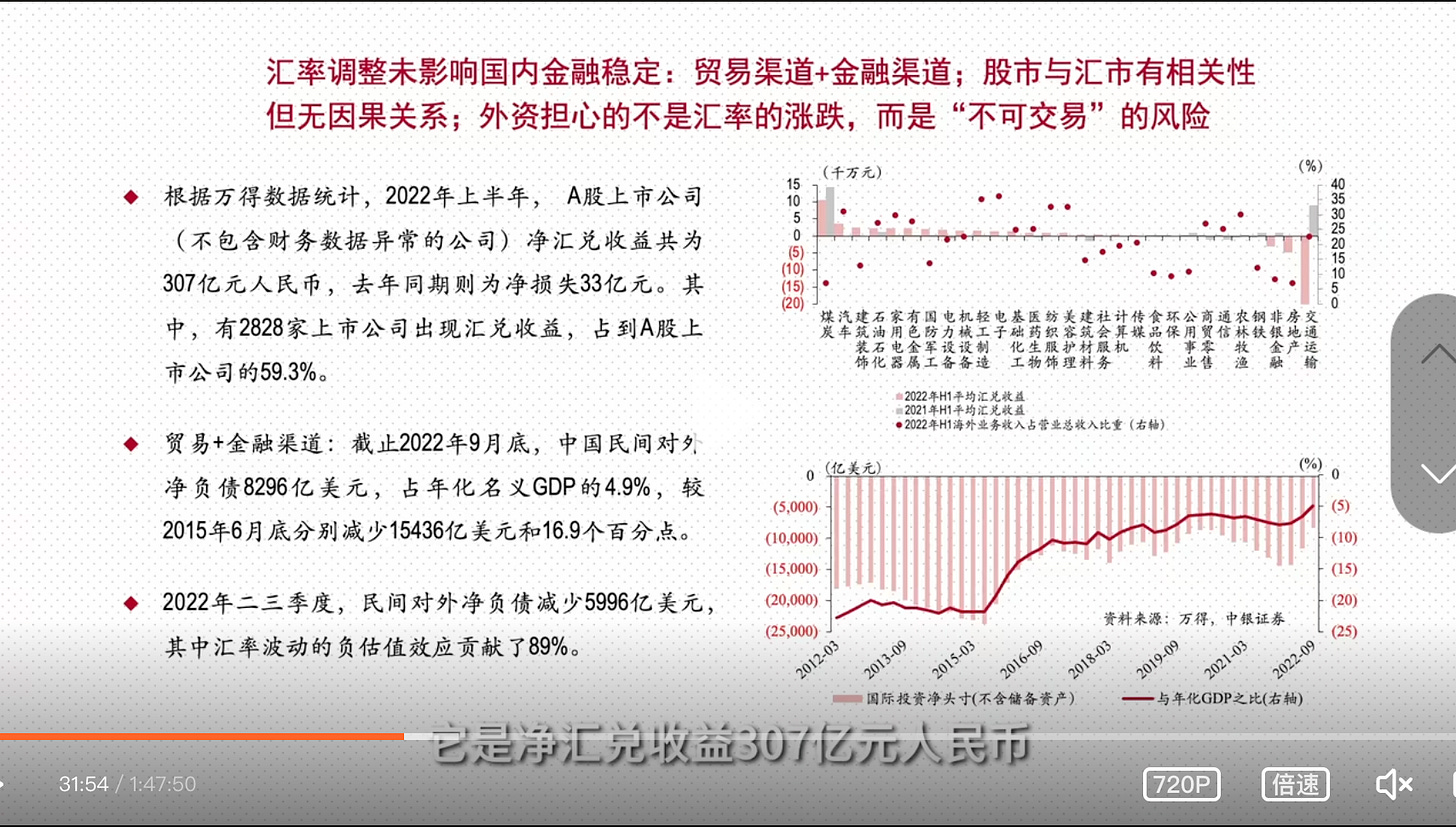

When discussing the impact of exchange rate fluctuations on financial stability, another topic that garnered more attention last year is the decline of the Chinese A-share market. Some people attribute the decline of A-shares to the depreciation of the Renminbi. However, I want to point out that, in fact, the correlation between the stock market and the currency market trend does not imply causality. We rely on data, not anecdotes. Currently, the publicly-traded companies’ annual financials have not been fully disclosed, so we turn to the data from the first half of last year. In the first half of last year, the Renminbi depreciated by 5.4%, leading to exchange losses for some listed companies and exchange gains for others. After netting, the listed companies' net exchange gains were 30.7 billion Renminbi, indicating that the depreciation of the Renminbi helps to improve the profitability of our listed companies. Conversely, in the first half of 2021, the Renminbi appreciated by 1%, resulting in net exchange losses of 3.3 billion Renminbi for our listed companies.

This indicates that viewing the depreciation of the Renminbi as solely negative is irrational for stock investors. While it's true that individual companies with significant foreign currency debt may see their debt burden increase, making it a valid reason for investors to be bearish on individual stocks, from the overall perspective of listed companies, Renminbi depreciation helps to improve profitability. From this perspective, the depreciation of the Renminbi should not be seen as a negative for A-shares.

The discussion often turns to the stock and currency "double kill," [double dip] especially recalling the 8.11 exchange reform period in 2015. At that time, the "double kill" had its rationale. Exchange rate depreciation affects the profitability of listed companies through two channels. The first is trade. As China' runs a trade surplus where the income in foreign exchange from exports dwarfs the payment in foreign exchange from imports, so the dip of the Renminbi was a net positive. The second is the financial side. Despite China being a net creditor globally, its private sector is a net debtor internationally. Renminbi depreciation increases the foreign debt burden.

Before the 8.11 exchange reform, the Renminbi had been on a unilateral appreciation trend for more than 20 years. Renminbi had also been a high-interest currency. So when people received U.S. dollars they would convert them to Renminbi quickly. That’s a practice known as asset Renminbization, and borrowing U.S. dollars for foreign payments, known as liability dollarization. That had led to the private sector accumulating a significant net foreign debt by the eve of the 8.11 exchange reform.

By the end of June 2015, the private sector's net foreign debt was $2.37 trillion, accounting for 22% of GDP. The initial stage of the 8.11 exchange reform saw an unexpected depreciation of the Renminbi, increasing China’s debt burden and triggering market panic, with many institutions, people, and enterprises increasing overseas asset allocation and prepaying foreign debt, causing a concentrated outflow of capital.

However, when studying this history, we must avoid missing the changes in circumstances. After two years of concentrated adjustment in 2015 and 2016, China's private sector's net foreign debt has greatly improved. By the end of September last year, the private sector's net foreign debt was only $829.6 billion, a reduction of $1.54 trillion from the end of June 2015, and its proportion to GDP fell by 17 percentage points. This shows that our private sector's currency mismatch degree has significantly improved compared to the period of the 8.11 exchange reform. In such a situation, the panic about the depreciation of the Renminbi is not as intense, and the negative effect of Renminbi depreciation through the financial channel is not as significant. Therefore, we cannot simply apply the experience of the stock market and currency "double kill" in the early stage of the 8.11 exchange reform to the present day. Instead, the increased flexibility of the Renminbi exchange rate now serves as a shock absorber, absorbing internal and external shocks.

In the second and third quarters of last year, China's private sector's net foreign debt decreased by $599.6 billion. This does not mean that foreign capital withdrew $600 billion from China’s private sector but is because holdings of Renminbi stocks, bonds, deposits, and loans, as well as foreign investment in China's equity investment, are priced in Renminbi. The accumulated depreciation of the Renminbi by 10.6% in the second and third quarters resulted in a decrease in the equivalent US dollar amount, contributing 89% to China’s private sector's net foreign debt reduction. This is what’s called 美元国际化 dollar internationalization, where the United States adjusts its debt burden through exchange rate fluctuations. In the process of Renminbi internationalization, if the exchange rate is flexible, we can gradually enjoy such benefits. This means that under the backdrop of financial opening, a flexible exchange rate policy is essential, and China is no exception.

For foreign investors, the risk of local currency exchange rate fluctuations is a natural part of investing in our financial market. They are not concerned about exchange rate fluctuations per se but are worried about supply not meeting demand.

If the exchange rate is not used to clear the market, then the only alternative is to resort to capital and foreign exchange control measures. This leads to non-tradable risks, namely, controlling inflows during appreciation, resulting in the inability to bring money in; and limiting outflows during depreciation, causing difficulties in moving money out. This is the primary concern for foreign investors. Hong Kong operates under a linked exchange rate system, sacrificing the independence of its monetary policy as a cost. The Chinese mainland, as a large open economy, requires a domestically oriented monetary policy. In such circumstances, to expand financial openness, the exchange rate must remain flexible. Last year, faced with the Federal Reserve's tightening and scattered outbreaks of the epidemic, we maintained the autonomy of our domestic monetary policy by increasing the flexibility of the Renminbi exchange rate.

We just discussed the considerations under exchange rate fluctuations: one is financial stability, and the other is price stability. We saw the return of global high inflation, but last year, China's CPI saw a moderate rise, with the whole year at only 2%, the core CPI at about 1%, and the PPI experiencing a unilateral decline. Starting from August last year, PPI began to drop year-on-year. So, inflation is not a significant problem in China. In the context of global high inflation, our prices remain essentially stable, ensuring basic livelihood while also broadening the autonomy of monetary policy.

But, as Governor Yi Gang stated during the International Monetary Fund autumn annual meeting in October 2018, China is a large country, and the currency policy of a large country prioritizes domestic concerns. This means our monetary policy's tightening or loosening does not depend on the Federal Reserve or cross-border capital flows but on our own growth, employment, and price stability situation. He also made it clear that any policy choice must accept the consequences it brings, including impacts on the exchange rate. Last year's significant adjustment of the Renminbi exchange rate to some extent reflected the divergence of Sino-US monetary policy, with the Sino-US interest rate differential turning from a positive to a negative, and the negative differential continuing to deepen. Any policy choice involves trade-offs, with both advantages and disadvantages.

We often hear in textbooks that financial opening and exchange rate rigidity is a dangerous policy combination. Last year, the increased flexibility of the Renminbi exchange rate and the significant improvement in marketization effectively supported China's push for institutional opening. Since 2018, whether the Renminbi appreciates or depreciates, the central bank has maintained the neutrality of exchange rate policy and regulatory policy, not initiating new capital and foreign exchange control measures, and at most, restarting some macro-prudential measures. We are steadily promoting the expansion of institutional opening, advancing the liberalization and facilitation of trade and investment.

In this context, in May last year, the International Monetary Fund conducted a revaluation of the special drawing rights basket currency, increasing the weight of the Renminbi by 1.36 percentage points. This affirmed China's progress in reform and opening up since the Renminbi's inclusion in the basket in 2015, especially in the aspect of financial reform and opening up. Over the past few years, our internal and external environment has been complex and variable. We jokingly say, if the Renminbi had not broken 7 in August 2019, in 2020 and 2022 the People's Bank of China would have had to “guard 7” around the clock, because within a day, the Renminbi exchange rate can fluctuate significantly. It is precisely because of the marketization of the exchange rate that we can truly reduce dependence on capital and foreign exchange control measures, promoting what is called institutional opening.

[[Zichen’s note: The level of 7 per dollar was seen by many as a psychological hurdle for the yuan, but Yi Gang, China’s former central bank govenor, has said that was no longer the case.]

The main conclusion of this part is,

First, as China's financial opening becomes increasingly open, the Renminbi exchange rate increasingly has the property of an asset price. Last year's wide fluctuation of the Renminbi was mainly driven by capital outflows, especially short-term capital outflows, leading to multiple equilibriums and exchange rate overshooting, easily influenced by market sentiment. The year-end economic data rebound was not strong, but with strong expectations and weak reality, the Renminbi still rose. In the foreign exchange market, as in the stock market, both Chinese and foreign capital operate under the same logic. In the last two months of last year, northbound capital through the Shanghai-Hong Kong Stock Connect saw a net inflow of more than 90 billion yuan, reversing the whole year's trend from a net outflow to a net inflow, demonstrating that investors are guided by market logic.

Second, the increased flexibility of the exchange rate helps to timely release pressure, avoid the accumulation of expectation, and play the role of a shock absorber, absorbing internal and external shocks. It can be said that, so far, the domestic foreign exchange market has withstood the test of severe fluctuations in the Renminbi exchange rate. The effectiveness of a market or mechanism is not judged by its smooth operation alone but by its resilience in the face of extreme market conditions. Overall, this set of institutional arrangements and policy operations has been successful.

Third, continuing to deepen the reform of exchange rate marketization, in line with China's high-quality development and high-level opening, helps to better coordinate development and security. We just discussed that the combination of financial opening and exchange rate policy rigidity is risky, a lesson confirmed by the experiences before and after the 8.11 exchange reform. China is no exception. Maintaining a flexible exchange rate policy enables better utilization of both domestic and international markets and resources, promoting the “dual economic circulation.”

Thanks for this.