Hu Bo: The Philippines’ Overblown Ambitions for Huangyan Dao/Scarborough Shoal

Director of SCSPI says Manila’s obsession faces the reality of China’s unyielding sovereignty and superior power; further provocations are only likely to tighten Beijing’s grip.

In the first episode of Deep Blue Dialogue, the South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI) launches its new online video series with an interview discussing the ongoing tensions between China and the Philippines surrounding Huangyan Dao (Scarborough Shoal).

Hosted by Yan Yan, Vice Director of SCSPI and Director of the Research Center of Oceans Law and Policy at the National Institute for the South China Sea Studies (NISCSS), the episode features an interview with Hu Bo, Director of SCSPI.

Key points from the interview include:

The Philippines’ “big ambitions, insufficient capability, and an obsessive desire for Huangyan Dao”: Despite their ongoing efforts, the Philippines lacks the strength to challenge China’s sovereignty over the area—China is simply “playing along” with them. Although China initially believed there was no need to station ships there daily, the Philippines’ actions have forced China to respond. The Philippines should stop creating more opportunities for China to act.

China’s firm position: China’s stance on Huangyan Dao has remained consistent. While showing considerable restraint toward the Philippines, China will not allow any infringement on its sovereignty. If the Philippines persists in its provocations, China will remain resolute in protecting its rights.

U.S. influence and the Mutual Defence Treaty (MDT): The United States plays a supportive role in the Philippines’ actions but has little interest in territorial disputes. While the Philippines often relies on the 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty with the U.S., the interpretation of the treaty remains ambiguous and ultimately subject to U.S. discretion. The U.S. commitment to defending Philippine claims in the South China Sea is not guaranteed.

The path forward: The most dangerous phase of tensions around Huangyan Dao may have passed, but ongoing frictions and confrontations are likely to persist for the foreseeable future. That is because the Philippines has a “short memory” and often misjudges the situation, so there is a need to continually remind them of their limits.

The episode is available on YouTube and Bilibili, the Chinese equivalent of YouTube. The series now has six episodes.

The interview was recorded on 14 October 2025 and released on 7 November 2025. It was conducted in Chinese, with the English translation of the transcript provided here.

Yan Yan: All right. In the first episode of Deep Blue Dialogue, we’re going to talk about Huangyan Dao, the frictions and confrontations surrounding it, the historical context, and possible pathways for resolving the issue. Our guest for today’s in-depth interview is Hu Bo, Director of the South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative. Good morning, Director Hu!

Hu Bo: Good morning! Good morning, Ms Yan!

1. The Philippines’ fixation on Huangyan Dao

Yan Yan: Huangyan Dao has remained a hot topic over the past two years. In November last year, China announced the baselines of its territorial sea adjacent to Huangyan Dao. Then, on September 10 this year, the State Council approved the establishment of a nature reserve for the shoal. Most recently, during the National Day holidays, China’s Coast Guard personnel raised the national flag in the waters off Huangyan Dao and held a series of ceremonies and activities.

As for the Philippines, they have, of course, continued to stir up trouble around the shoal. Just yesterday [13 October, 2025], I saw a long post on X by Philippine Coast Guard spokesperson Jay Tarriela, in which he claimed they had successfully carried out a major supply-delivery mission under their “Kadiwa para sa Bagong Bayaning Mangingisda” (KBBM) initiative. They organised around four coast guard vessels and eleven supply boats to deliver fuel subsidies, crushed ice, and large packages of daily necessities to nearly a hundred Filipino fishing vessels operating near Huangyan Dao and Xianbin Jiao. He also said the “mission concluded” for the Philippines.

So, Director Hu, I’d like to ask: how do you view the current situation around Huangyan Dao?

Hu Bo: The reason the Philippines is so fixated on Huangyan Dao is largely because it believes it “lost” the shoal in 2012. What happened in 2012? At that time, the Philippines seized Chinese fishermen inside the lagoon of Huangyan Dao and even forced them to strip their tops off under the sun on the boat deck, which caused a very strong reaction in China. China’s Fisheries Law Enforcement and China Marine Surveillance vessels then intervened, leading to a standoff with Philippine ships.

Later, Manila felt it could no longer sustain the confrontation and asked the United States to mediate, after which it withdrew its vessels. Due to this Philippine action, China began maintaining a long-term presence at Huangyan Dao from 2012 onward. Manila regards this as a major grievance and is unlikely to move past it in the near future, so it will certainly continue to provoke around the shoal.

After China set the territorial-sea baselines last year, Manila’s main tactic has been to exploit what they call “fishing presence” to illegally enter China’s territorial waters around Huangya Dao, and to send aircraft into the surrounding airspace. Their goal is to undermine China’s control over the surrounding waters of the shoal. At present, their actions are mostly what you just described: fishery activities, supply deliveries, and repeated attempts to cross into China’s territorial waters and airspace near Huangyan Dao.

From October 8 to October 10, the Philippines carried out a so-called fisheries resupply operation. Manila is saying it was a success—well, if that makes them happy, so be it.

2. The Philippines often misreads the situation

Yan Yan: Back in 2012, the Philippines detained Chinese fishermen. But look at where things stand now. The China Coast Guard is patrolling regularly around Huangyan Dao, and the Philippines says there are more than a dozen Chinese coast guard vessels operating in the waters near the shoal, with naval ships and aircraft also in the mix. There are even reports that China’s H-6K bombers are deployed there on a long-term basis. Given all that, does Manila really believe they could take back control of Huangyan Dao?

Hu Bo: I think the Philippines may be misreading the situation. As a country, its assessment of both the broader international environment and the realities on the ground may involve some misunderstandings.

Take what China has deployed — the H-6K bombers you mentioned, plus some naval forces. In my view, none of that is really aimed at the Philippines. They’re deterrent and contingency measures in case the United States becomes directly involved. The Philippine defence secretary has even said the systems showcased in China’s military parade are meant to “intimidate” the Philippines. But honestly, those capabilities weren’t developed with the Philippines in mind.

As a country, the Philippines sometimes misreads the bigger picture by a wide margin. From China’s perspective, they don’t really stand a chance—it’s just not going to happen. And the China Coast Guard presence around Huangyan Dao today is nothing like it was more than ten years ago.

Still, you can’t judge the Philippines by normal logic. The Philippines think they have a few cards to play. For one thing, they believe they have strong diplomatic and public opinion backing, that a lot of countries are on their side. So they enjoy themselves; they kind of get stuck in that mindset: if so many allies and partners are supporting them, then they convince themselves they have legal and diplomatic cover. That creates some major illusions.

They also believe they are modernising their military and that the United States has their back. Put together, that gives them at least some confidence that they can regain control of Huangyan Dao. Of course, whether they can actually take it back might not even matter that much to the Philippines, the Marcos Jr. administration, or even their Coast Guard and armed forces. What matters more is the domestic political payoff: being able to say, “China is a threat, and we acted.” After each operation, they praise themselves, highlight how “successful” the mission was, how “professional” their forces and coast guards were, and how they stood up to China’s so-called “bullying,” and so on.

So whether they can actually retake the shoal is a separate question, and I don’t think they lose much sleep over it. But rhetorically, they will certainly frame China’s control of Huangyan Dao as “illegal” or “illegitimate,” using language along those lines. In practice, I think what seems to matter more is using the issue as a domestic political lever: to boost their visibility, justify bigger budgets, and showcase the supposed strength of the Philippine armed forces and Coast Guard.

3. The Huangyan Dao Nature Reserve

Yan Yan: Exactly. I saw a poll recently putting Sara Duterte’s trust rating above 60 per cent. That’s got to put Marcos Jr. under even more pressure, and it probably makes him want even more to play the national-hero role, especially by painting China as this “maritime bully.” So I wouldn’t be surprised if the Philippines takes more actions near Huangyan Dao, and in other parts of the Nansha Islands (Spratly Islands) too.

Now, China announced on 10 Sept. that it’s setting up a nature reserve at Huangyan Dao. Director Hu, a lot of people are watching what happens next. If the goal is to protect coral reefs, then inside the reserve—especially in the core area and the experimental zones—big construction sounds unlikely. But outside the reserve, on other parts of the reef flat, could there be room for basic facilities like an observation post, a duty station, or a small port or pier to make day-to-day management easier?

Hu Bo: I think anything is possible. China is a peace-loving country—indeed, we are. China usually responds only after being provoked. If the Philippines keeps pushing things further, of course, the nature reserve was set up mainly for environmental protection, and China has sovereignty over Huangyan Dao, so moves like this are completely justified. My assessment is that, for now, there’s no real need right now to build permanent facilities there.

But all of this will depend on what the Philippines does next. Right now, they’ve got dozens, sometimes over a hundred, fishing boats operating regularly around the shoal, though they stay outside the territorial sea. Setting up the nature reserve was, in large part, a response to excessive Philippine fishing in the area, which has caused environmental damage. So if the Philippines keeps ramping up the damage, I believe China will take corresponding measures, including the kinds of facilities you mentioned, to support environmental protection and management there.

China can certainly do it—it’s not like it is unable to build facilities. If China wanted to, it could move fast, and the Philippines wouldn’t be able to block it. China is not doing it right now; it is showing a high degree of self-restraint. But if the Philippines keeps provoking beyond a certain line, then even island-building, including land reclamation, would remain on the table as a possible option.

4. Is China’s South China Sea Policy Consistent?

Yan Yan: I really look forward to future developments in the Huangyan Dao area. Do you think that playing the environmental protection card at Huangyan Dao—moving from the past decade’s reliance on regular law-enforcement presence by the Coast Guard, marine surveillance, fisheries agencies, and even the navy, to a more ecology-based approach to maritime rights protection and governance—signals a shift in China’s maritime policy?

Hu Bo: I think the outside world may be reading too much into this. Huangyan Dao is a Chinese sovereign territory. China today emphasises “green mountains and clear waters,” and environmental protection is being pursued across the board—on the mainland, in internal waters like the Yangtze and Yellow rivers, and throughout inland river systems—as part of one overall approach. Huangyan Dao is part of China’s sovereign domain, so of course, China places great importance on protecting its environment.

In my view, this is a decision driven primarily by domestic considerations. The ecosystem around Huangyan Dao is extremely fragile, and some activities have already caused visible damage. So China is putting environmental protection measures in place. It doesn’t need to use “environmental protection” as an excuse to beef up its presence there.

And more than anything, I think this fits into China’s national environmental strategy, part of a whole-of-nation approach. Does the Philippines matter in this? Sure, because right now the biggest source of environmental damage around Huangyan Dao is the Philippines. Their fishing methods are very rudimentary, and there’s a lot of human waste being left on the reef flats nearby. So in that sense, stepping up environmental protection there helps China, helps ordinary people, and in the end helps the world too.

5. Historical basis for the sovereignty of Huangyan Dao

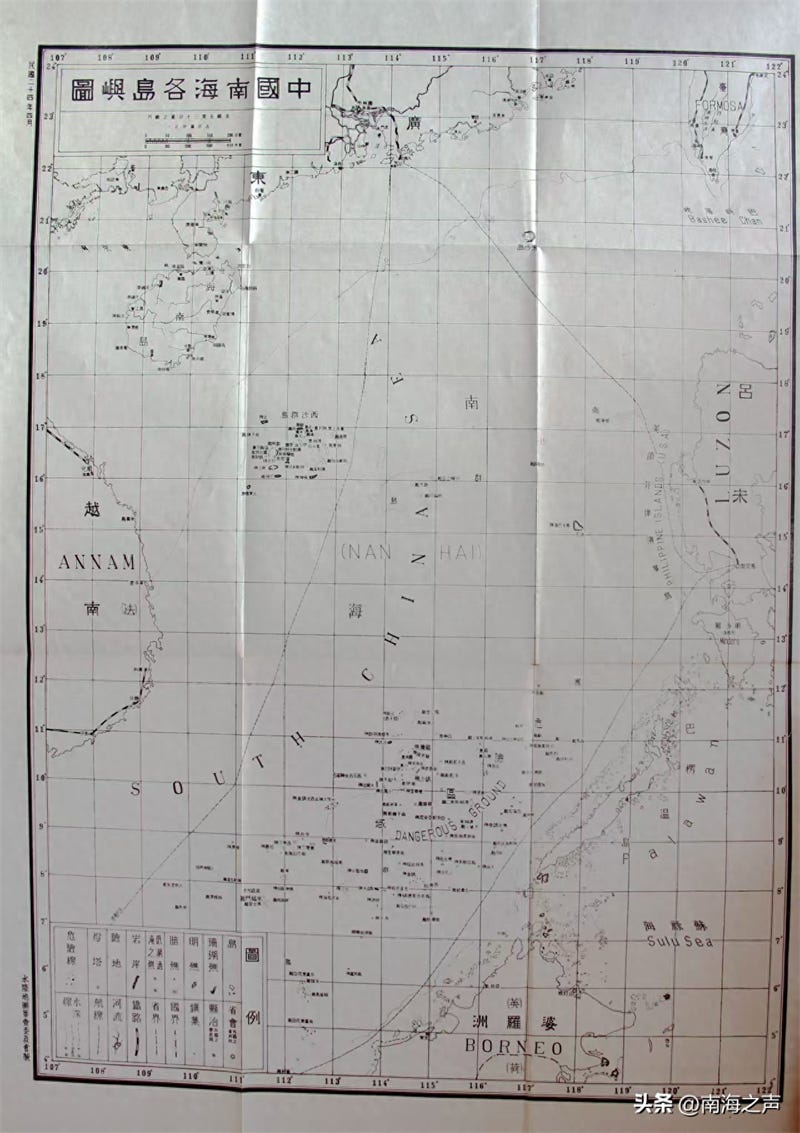

Yan Yan: Right. China already has several coral-reef nature reserves in Hainan, like in Sanya and around Wuzhizhou Island. And like Director Hu just said, China does not view Huangyan Dao as disputed territory. Chinese authorities, across different historical periods, have exercised continuous and effective administration over the shoal. There are records across dynasties, in historical texts, local gazetteers, and official maps. Modern-era evidence is even more abundant.

For example, in 1935, the Republic of China’s Land and Water Maps Inspection Committee published the Chinese and English names of islands in the South China Sea. And in 1983, the People’s Republic of China’s Committee on Geographical Names released an official list of standardised Chinese and English names for features in parts of the South China Sea, in which the Chinese and pinyin names for Huangyan Dao are explicitly included.

So I would like to ask you again, Director Hu: Why does the Philippines believe it has sovereignty over Huangyan Dao? What exactly is its claim?

Hu Bo: The Philippines didn’t start claiming Huangyan Dao until the 1990s, when it said the shoal was terra nullius—belonging to no one. Can you believe that? By the 1990s, was there really still “nobody’s land” like that anywhere in the world?

As you noted, China’s sovereignty claim over Huangyan Dao can be traced back at least to the Yiwu Zhi (circa 89-105), a regional gazetteer-style work from the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 A.D.), which records the shoal’s name and description. And during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Guo Shoujing (1231-1316) personally carried out astronomical and hydrological observations at Huangyan Dao.

So sovereignty isn’t decided by who’s closer on the map. International practice points to a set of commonly cited principles: first discovery, first naming, and first effective and continuous administration. By those measures, China’s claim to Huangyan Dao rests on a long historical record. China was already a unified, fairly advanced state early on, while the Philippines back then, was still made up of tribal societies.

And in modern history, the Philippines was under Spanish rule for over three hundred years, and then under U.S. control for around fifty years. But neither Spain nor the United States made sovereignty claims over Huangyan Dao or the Spratly Islands; there are clear records of this in documents and treaties.

After the Philippines gained independence, I think it picked up a kind of “post-colonial syndrome.” Countries that have experienced colonisation sometimes develop ambitions that outstrip their capabilities, and in some cases are even bigger than those of their former colonial rulers. To me, the Philippines fits that symptom. After independence, nationalism took off, and Manila began looking out to sea for islands to “discover,” basically copying the old colonial playbook—the Magellan, Age-of-Exploration mindset: “If we find an island, then it belongs to us.”

But times have changed. By that point, how could there still be terra nullius? That’s why they didn’t even formally claim Huangyan Dao until the 1990s. In my view, it’s pretty ridiculous.

6. Will the U.S. intervene for the Philippines?

Yan Yan: Do you think that this inflated ambition and limited capabilities might also be driven by the belief that the United States will back them up as an ally, giving them extra confidence? Because from the perspective of territorial treaties, the Philippines’ territory was essentially defined by three agreements: the 1898 Treaty of Paris between the U.S. and Spain, the 1900 Treaty of Washington (U.S.–Spain), and the 1930 Convention between the United States and Great Britain. These treaties clearly place the westernmost boundary of Philippine territory at the 118°E meridian.

But I feel that the treaty Manila brings up the most these days is actually the 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines. So, I’d like to ask you, Director Hu: How meaningful is the Mutual Defence Treaty (MDT) in practice? Can it really deliver the kind of support the Philippines hopes for?

Hu Bo: First of all, the Mutual Defence Treaty between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines has nothing to do with the Philippines’ sovereignty claims. First off, it’s a defence pact. If you read the wording—and this part of U.S. policy hasn’t changed—it applies to the Pacific area, and the South China Sea is part of it. So actions there could fall within the treaty’s coverage.

That said, the U.S. policy has somewhat shifted. In the past, Washington did not explicitly say whether Huangyan Dao or the Spratly Islands were covered by the MDT. Legally, in my view, the treaty’s coverage has always been there—that hasn’t changed. What has changed is the messaging: the United States used to say less about it, and now it says more. That in itself is a signal.

But one shouldn’t read too much into that. U.S. policy hasn’t fundamentally changed; Washington is simply emphasising it more now as a way to stir things up for China and deter China.

It is also important to understand that the U.S. alliance system in Asia is different from the one in Europe. In Europe, it’s multilateral, while in Asia, it is bilateral. In a multilateral framework, the United States faces stronger obligations, or rather, stronger incentives to follow through, because failing to act would be seen as betraying more than 20 countries at once. In these one-on-one treaties—whether with Japan, Australia, or the Philippines—the key collective defence provisions, mainly Articles IV and V, state that if one party is subjected to an “armed attack,” the other will take action. But the language is highly vague.

And the MDT with the Philippines is even less specific than the U.S. treaty with Japan. One way to put it is that Washington is more willing to follow through for Japan than it is for the Philippines.

Even so, when the United States would actually step in is a highly complicated question. Procedurally, the Philippines would first need to request that the two sides convene their joint commission to assess the situation, after which each side would have to proceed through its respective domestic legal procedures. In other words, the procedures and all those ambiguities give Washington enormous room for manoeuvre.

If the U.S. wants to get involved, it can always find a way to justify it—even a water-cannon incident could be framed as an “armed attack.” If it doesn’t want to follow through, then even gunfire might not count. It could always be argued that it wasn’t a sustained armed attack, so it doesn’t trigger the MDT. So basically, the U.S. gives the Philippines an ambiguous commitment, and the Philippines tries to use its geographical location to turn that vagueness into leverage. That’s how it works.

Also, the goals of the two sides are different. The U.S. is, of course, a big player in the South China Sea issue. It wants to use the China–Philippines tensions to push forward its own strategic goals, like its positioning in the Indo-Pacific and its plans around the Taiwan Strait. The U.S. doesn’t really care about Ren’ai Jiao (Second Thomas Shoal) or Huangyan Dao. It’s a little more concerned about Huangyan Dao because it thinks that once China fully controls it, China’s power in the region would be significantly strengthened. So for the U.S., it’s all about its competition with China; the sovereignty issue itself is not its primary concern.

Thus, the U.S. wants to see ongoing incidents in the South China Sea, but nothing too serious. Because if something truly serious were to happen, the U.S. would be forced either to honour its treaty obligations or to admit it is backing down. Both outcomes would be costly: not responding would hurt its credibility and make it harder to lead in Asia and globally. The U.S. mindset is simple: they welcome small, daily disruptions, but a major crisis is something they want to avoid.

This pattern is clear. In 2022 and 2023, the Marcos Jr. administration kept bringing up the MDT. But in the last year or so, they’ve mentioned it much less, particularly since the June 17 incident last year. I think one big reason is pressure from the U.S. Publicly, Washington is pushing China, of course. But privately, I believe the U.S. is also telling the Philippines: “Don’t take this too far. If you escalate too much, no one will be able to manage the situation.”

So now Marcos Jr. hardly ever mentions the MDT, and instead says, “We can handle this ourselves, we don’t need the U.S.” This gives the U.S. a convenient excuse to say, “If you’re not asking for help, then I don’t need to step in.” Right now, the U.S. support for the Philippines mainly comes through diplomacy, public opinion, and intelligence. For example, during Philippine operations, U.S. patrol planes like P-8s or MQ-9s are often in the area, conducting situational awareness. But right now, the U.S. has no intention of stepping in directly to help the Philippines defend its claims on the ground. The goals of the two sides just don’t match.

I believe the Philippines is far from confident that the MDT will truly be honoured. That’s why it has begun seeking out other partners—Japan, the U.K., and Australia—trying to pull in as many countries as possible to create a stronger military presence. It’s like walking in the dark, whistling just to feel a bit more secure.

7. Impact of Huangyan Dao on China–Philippines relations

Yan Yan: So, the power to interpret the MDT lies more with the United States than with the Philippines. Given how the Huangyan Dao issue has developed, what kind of impact do you think it has had on China–Philippines relations over the past few decades?

Hu Bo: Here’s how I see it. First, let’s look back a bit. After Marcos Jr. came to power, he began taking actions in what he calls the “West Philippine Sea.” In the south, mainly the Spratly Islands, the Philippines has acted on Ren’ai Jiao and Xianbin Jiao (Sabina Shoal). In the north, the focus has been on Huangyan Dao. After years of tension, especially after the June 17 incident last year, I think the Philippines really felt the impact. In the south, especially at Ren’ai Jiao, there’s not much room left for them to advance, and the risks of escalation are high.

So, starting around 2024, the Philippines gradually shifted its focus to Huangyan Dao. To put it simply, even though there are still smaller, daily frictions in the south at Ren’ai Jiao and Xianbin Jiao, I believe the Philippines won’t try any big moves there anymore. The reason is that, first, China responds very quickly and firmly, and second, pushing things further would come with huge risks, even the possibility of armed conflict.

Thus, the Philippines’ “struggle” is now focused on Huangyan Dao. I believe Huangyan Dao will not only remain a key focal point in China–Philippines relations, but will also be central to the entire South China Sea situation. It has become the hotspot of hotspots. My current judgment is, the Philippines’ determination to continue provoking China over Huangyan Dao should not be underestimated, even though its capabilities are clearly limited.

For the foreseeable future, the situation around Huangyan Dao is likely to remain as it is now: the Philippines will continue intruding, and China will continue pushing them out. Confrontations, including standoffs, ramming, water cannon incidents, and possibly other forms of escalation, will persist. China does not desire this situation, but unfortunately, it has little choice. If the Philippines continues challenging China’s sovereignty and red lines, China will have no option but to respond. As a result, these frictions won’t stop, and as long as they continue, China–Philippines relations will struggle to return to normal. It will take time and the right circumstances for relations to normalise again.

Yan Yan: Indeed, as you mentioned, the Philippines may remain in this situation for a long time—they provoke, China drives them away or expels them. Does that mean China will need to keep investing heavily in regular patrols and control operations? For comparison, in the East China Sea, China’s regular patrols around the Diaoyu Islands are present at least 350 days a year; I believe it was 355 days last year. It seems that the effort required around Huangyan Dao will be even greater, not less, than in the East China Sea. So, in terms of national strength and economic capacity, will maintaining regular patrols around Huangyan Dao present any difficulties or challenges?

Hu Bo: Huangyan Dao is a long way from both the Xisha Islands (Paracel Islands) and the Nansha Islands, which are China’s frontline bases. The distance is over 600 kilometres. Huangyan Dao itself also covers a vast area. It is often viewed as a “point” on the South China Sea map, but when you zoom in, the inner lagoon—the triangular lagoon area—is over 130 square kilometres. After establishing territorial seas around it, the total area China needs to manage is nearly 2,600 square kilometres. Only megacities in China, like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou, cover such large areas; most cities are much smaller.

Managing such a vast maritime area is certainly difficult. Defence at sea is very different from defence on land. On land, you can secure key roads and access points, which essentially gives you control of the area. But at sea, the defensive depth is immense. Trying to completely secure a 2,600-square-kilometre area with just a few vessels, or even dozens, is unrealistic in the short term. That’s one aspect of the challenge.

The Philippines, on the other hand, is geographically closer. If China sends small ships, their endurance is limited; but if China sends larger ships, they will struggle to gain an advantage in this “cat-and-mouse” game, because the Philippines’ smaller fishing boats are more agile and manoeuvrable. So, yes, this does present challenges for China.

However, I view these as technical challenges. The more important aspect, at the strategic and policy levels, is that for both Huangyan Dao and China–Philippines tensions, China needs to stay calmly confident. After two or three years of these confrontations, it’s evident that the Philippines doesn’t have much real power. What can they really do? Not much. Their challenge is more of a nuisance than a real threat. As long as the United States does not directly intervene, they cannot pose any substantive threat to China.

Of course, diplomatically and in terms of public opinion, their actions are harmful, and China must respond accordingly. But that’s a different matter altogether.

Internally, however, China must maintain strategic confidence. On the frontline, flexibility is needed; there’s no need to remain overly tense. More than ten years ago, they couldn’t take Huangyan Dao; do they have any chance of doing it now? No way.

Yan Yan: They really don’t have any new tricks up their sleeve.

Hu Bo: They don’t. They’ve basically exhausted all the tactics they have. It’s just the same old moves.

Yan Yan: My sense now is that their tactics are based on the unequal capabilities between China and the Philippines. They seem to be intentionally playing the victim. For example, to the international community, it appears that China has its coast guard vessels, navy ships, and aircraft in the area. Meanwhile, the Philippines launched the “Kadiwa para sa Bagong Bayaning Mangingisda” (KBBM) initiative, organising and encouraging fishermen to head to the frontline to fish since June of this year.

Hu Bo: The fishing boats are just an excuse. They say, “Look, our fishermen are out there, so we have to send our fisheries vessels and coast guard to protect them.” But there is absolutely no need for this protection, because China has no intention of doing anything to those fishermen. So, what exactly are they protecting? Thin air? They’re simply using fishing activities as an excuse. The same thing applies in the air domain—they just look for anything they can use to justify their actions.

Right now, the real collisions and confrontations are mainly caused by the Philippine Coast Guard and fisheries vessels ramming into China’s territorial waters, challenging China’s control over Huangyan Dao. For years, their fishermen have operated there without friction with the China Coast Guard. The future is uncertain, but as of now, the fishermen are not maritime militias or anything of the sort, as some have imagined. What they mainly provide is a convenient excuse for the Philippine government.

8. The path to future resolution

Yan Yan: They’re just creating a story for themselves. With what they’ve been doing lately, the message they’re sending is: “We’re bringing big care packages to the fishermen—water, fuel, and all that.” But really, it’s just a cover for their operations, a way to justify what they’re doing.

Now, looking to the future. China’s stance is very firm: it absolutely doesn’t see Huangyan Dao as disputed territory. But the Philippines won’t give up its claims either. If, in the future, China takes new steps in the Huangyan Dao Nature Reserve or introduces new measures or policies, such as more detailed management regulations, I imagine the Philippines will respond in some way. So, how do you think the situation around Huangyan Dao will play out over the next three to five years? And in the long run, is there any chance of resolving this issue?

Hu Bo: Like I said earlier, most of China’s actions right now are reactive. First, China firmly defends its sovereignty and maritime rights, and there’s no doubt about its determination on this. Especially since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, the results have been clear.

At the same time, China wants to keep things stable in the South China Sea. China doesn’t want major disruptions in the area. So, while China sees Huangyan Dao as part of China’s sovereignty, its actions have remained restrained. However, if the Philippines continues its provocations, then, as I mentioned before, options like island building, including land reclamation, are still on the table.

As for what will happen, I don’t think things will calm down in the next three to five years. Huangyan Dao and the South China Sea in general will not settle into quiet. The situation will likely remain at a simmer, around 70 to 80 degrees Celsius. It won’t boil over, but it won’t cool down to 60 degrees either. After all, China cannot control the will of other countries. So, for the next three to five years, the situation will likely stay as it is now.

Of course, there could still be surprises. The Philippines might suddenly make a big move, as they often misjudge the situation. If that happens, China’s response will be more significant.

China’s years of experience in protecting its rights have taught it an important lesson: the greater the challenge, the greater the opportunity. On the one hand, China does not seek trouble. But if trouble does arise, there is no need for concern. With China’s current strength and capabilities, it can accomplish much more and take a variety of actions. But why hasn’t China taken those actions yet? Because China exercises self-restraint. However, if the Philippines continues to push China too far, then, at a certain point, some issues might just be resolved. That’s the logic.

China’s policy has remained consistent over the years, despite what some may claim. Many Chinese domestic observers, including netizens, believe China is constantly changing tactics or playing some “grand strategy.” But really, nothing has changed. China’s approach to the Nansha Islands has always been: shelve disputes, but ensure no new losses. If any country tries to inflict new losses on China, whether in the Nansha or at Huangyan Dao, that is something China cannot tolerate and will firmly oppose. This has always been clear.

China’s policy and position have been consistent. But why do some people outside of China perceive China as “bullying others”? It’s because, when China was weaker, its responses were less visible. Now that China is stronger, even small reactions seem much larger, which leads people to think the policy is changing. This is a misunderstanding. The policy has remained the same all along.

Of course, Huangyan Dao is different from the Nansha. China doesn’t recognise any dispute over Huangyan Dao, but the logic is similar. In other words, China will not tolerate anyone taking control of Huangyan Dao or occupying any unoccupied feature in the Nansha. China will do whatever it takes to stop that. We’ve seen this at Ren’ai Jiao and Xianbin Jiao, and the Philippines understands this.

So, when it comes to China’s response, people like to guess what China will do. But what China does depends on what the Philippines does. If the Philippines is content with the current situation, then China can “play along with it.” But if the Philippines isn’t satisfied and decides to escalate, China has a lot more options to consider.

That said, China still hopes the situation will cool down and the tensions will ease. But in the next year or two, or even the next two or three years, that’s unlikely. As I mentioned earlier, provocations around Huangyan Dao have become a lifeline for the Philippine Coast Guard, the Philippine armed forces, and the Philippine Department of National Defence.

In fact, over the past two years, it’s clear that Marcos Jr.’s tone has softened quite a bit. When he first took office, he said he wanted to remove all Chinese personnel and equipment from what they call the “West Philippine Sea,” including forcing China to withdraw from Meiji Jiao (Mischief Reef). They sent over a hundred diplomatic notes to China’s Foreign Ministry demanding this. But now, his tone has changed significantly.

Recently, due to domestic political issues, Marcos Jr.’s focus has shifted away from Huangyan Dao and likely from the sea in general. But it is important to highlight that many countries share the same view about the Philippines—that it is very difficult to deal with. The Philippines is, in a sense, a fragmented country. At the very least, China is now dealing with two different Philippines. One is the Philippines, represented by its diplomatic establishment. They genuinely hope to resolve issues with China through diplomatic channels, and they highly value the Bilateral Consultation Mechanism (BCM) on the South China Sea, which helped ease tensions at Ren’ai Jiao and at Xianbin Jiao. They want to keep using diplomacy to deal with problems going forward.

But the Philippine Coast Guard and military operate with another logic. They want to stir things up every day and keep the confrontation going. Right now, it’s the military and the coast guard making the most noise. One major reason for their aggressiveness is that the Philippines is pursuing “defence modernisation.” To justify a larger budget and more resources, they need to create tension.

Of course, the U.S. factor is often mentioned, but this current wave of Philippine provocations, I think, is primarily driven by the Philippines itself. The U.S. plays more of a supporting role or an “add-on” factor. What matters more is that the current Philippine administration—including the president, the military, and the police—has too many ambitions, which are unrealistic and exaggerated.

And that’s how we arrived at the current situation. After two or three years of friction with the Philippines and the lessons they’ve learned from these incidents, it’s clear that they now understand China is very serious about this issue.

I think the most dangerous phase may already be over. The critical period of the China–Philippines tensions in the South China Sea may have passed. But there’s another issue: as a political system, the Philippines has a very short memory. One confrontation might make them cautious for three months, maybe half a year at most. That’s why it’s so important for China to keep showing firm will and determination to protect its rights through concrete actions. If not, the Philippines will misread the situation. They could think, “China’s busy with other things,” or “Look, the U.S. seems to be backing us. Now’s our chance.” That was the misjudgment by the Marcos Jr. administration in 2022 and early 2023. It’s important to keep an eye on this.

Then, last year, when China announced the baselines and base points for its territorial sea, all of that was triggered by Philippine provocations. Previously, China believed its sovereignty was clear, and there was no need to station ships there every single day. But because of the Philippines’ actions, well, this is the result. I often say this to the Philippine side, both publicly and privately, because it’s simply the truth: if they continue with this, they are only creating more opportunities for China.

Yan Yan: Exactly. So please, don’t give China opportunities to take further action. And before China announced the territorial sea baselines for Huangyan Dao last year, the Philippines had already passed its Archipelagic Sea Lanes Act—its new maritime baselines law—in which it once again included Huangyan Dao. I think they themselves are very aware that their legal and historical basis for claiming the shoal is completely insufficient. That’s why they now feel the need to pass new maritime laws to patch up those legal shortcomings.

In today’s first episode, we took a detailed look at the Huangyan Dao issue. To summarise the Philippines in one sentence: big ambitions, insufficient capability, and an obsessive desire for Huangyan Dao.

As for the United States, its strategic objectives in the South China Sea are entirely different from those of the Philippines, and the authority to interpret the 1951 Mutual Defence Treaty between the United States of America and the Republic of the Philippines also lies in Washington’s hands.

China’s policy positions and claims in the South China Sea have been consistent. And on the issue of Huangyan Dao, China has shown great restraint and goodwill toward the Philippines.

According to Director Hu Bo, the most dangerous phase at Huangyan Dao has passed, but the ongoing tensions and confrontations will likely continue for quite a long time.

Thanks, Director Hu, for your in-depth analysis. If you’re interested in more insights and deep dives on maritime issues, don’t forget to like, follow, and subscribe. See you next time.

This clause makes no sense: "fisheries vessels ramming into China’s territorial waters".

You complain about rudimentary Filipino fishing methods that are not environmentally modern. You do not complain about Chinese industrial fishing methods that destroy fishing grounds instead of allowing them to replenish.

Filipinos have fished these seas for hundreds of years. The PRC does not use its clout to work out a sharing of the seas. Instead, it argues from the ancient imperial logic of "sovereignty." What kind of socialism is that?

Lee Kwan Yew: "The Philippines press enjoys all the freedoms of the US system but fails the people: a wildly partisan press helped Philippines politicians flood the marketplace of ideas with junk and confuse and befuddle the people so that they could not see what their vital interests were in a developing country. And, because vital issues like economic growth and equitable distribution were seldom discussed, they were never tackled and the democratic system malfunctioned. Look at Taiwan and South Korea: their free press runs rampant and corruption runs riot. The critic itself is corrupt yet the theory is, if you have a free press, corruption disappears. Now I'm telling you, that's not true. Freedom of the press, freedom of news critics, must be subordinated to the overriding needs of the integrity of Singapore and to the primacy of purpose of an elected government