Jiang Ming'an: Caging the Leviathan is the Dream and Pursuits of Chinese Scholars of Administrative Law

72-year-old PKU professor details the development of administrative law, its effects on the Chinese people and the Communist Party of China, and vows continuous effort toward democracy & rule of law

On October 6th, the seminar on "The Formation and Prospects of Contemporary Chinese Administrative Law" was held, hosted by the Law School of Peking University and the Constitutional and Administrative Law Research Center of Peking University. Professor 姜明安 Jiang Ming'an delivered a keynote speech titled "Caging the Leviathan: The Dream and Pursuit of Chinese Scholars of Administrative Law."

After meticulously going through the development of Administrative Law in China, Jiang summarized its impact on China.

The first aspect is the change in the mindset of the Chinese people, which includes three significant shifts:

First, the traditional belief that "the people's government is inherently correct and acts in the interests of the people" is gradually shifting towards the understanding that "the people's government can make mistakes and infringe upon the rights of the people. Therefore, its power must be regulated by law to prevent it from transforming into the Leviathan."

Second, the concept of the relationship between officials and citizens as akin to "parent-officials" and "subjects" is evolving into a view of "public servants" and "masters," where public servants can only act with legal authorization, and citizens are free to do anything that the law does not explicitly forbid; not the other way round.

Third, the old notion of "citizens do not sue officials" or "citizens do not contend with officials" has changed to "citizens can not only sue officials but can also win against them," embracing the principle that “power comes with responsibility; the exercise of power requires oversight, official violations of the law entail lawsuits, and any infringement upon rights must result in compensation.”The latter principle, except for "violations of the law," which is my own input, was originally proposed by Premier Wen Jiabao and incorporated into the Program for Comprehensively Promoting “Administration by Law”. It is indeed a very valuable summary.

The second aspect is the significant transformation in governance methods, which mainly includes four points:

First, the operations of administrative agencies and their staff have shifted from following directives, orders, and official documents from higher authorities to adhering to the principle of administration according to law.

Second, the methods of administrative management have moved from being unilaterally coercive to placing greater emphasis on participation and interaction.

Third, the means of administrative enforcement have evolved to primarily regulation, also incorporating flexible approaches like administrative agreements and guidance, as well as soft tactics.

Fourth, administrative activities have transitioned from prioritizing speed and efficiency to giving greater attention to the due process of law and the protection of the rights and interests of administrative subjects.

The third aspect is the significant changes in the objectives of the CPC, mainly in three respects:

First, the Party has shifted from being guided by the policy of taking class struggle as the main line and the singular pursuit of GDP growth and economic and material development to also striving for fairness and justice, and the advancement of social, ecological, and political civilization.

Second, there has been a gradual transition from ruling the country primarily through policy to governing according to the rule of law.

Third, there has been a move away from an excessive focus on order and "stability maintenance" towards a greater emphasis on the protection of human rights and the lawful rights and interests of citizens, legal persons, and other organizations. The Party changes. Everything does. But what remains unaltered and unalterable is the imperative to cage Leviathan and tame Leviathan.

Jiang concluded his speech by saying

Caging the "Leviathan" is the dream and pursuit of Chinese scholars on administrative law. For this, we have been exploring for forty years, but we are still far from our original dreams and goals and need to continue our efforts. Democracy and the rule of law have not yet been realized and we must continue to strive!

The following is a translation of Jiang’s speech, provided in full to Pekingnology.

A WeChat blog operated by the opinion department of Phoenix TV’s website had published its main points.

(Photo via the Procuratorate Daily, the official newspaper of the Supreme People’s Procuratorate.)

(Photo via Law School of the Central University of Finance and Economics )

把“利维坦”关进笼子:中国行政法学人的梦想与求索

Caging the Leviathan: The Dream and Pursuit of Chinese Scholars of Administrative Law

Distinguished guests, scholars, and friends,

Thank you all. The topic of my speech today is "Caging Leviathan—The Dream and Pursuit of Chinese Scholars of Administrative Law." The dream refers to our objective, which we have been working towards for decades: to cage Leviathan, to control Leviathan, to tame Leviathan—that has been our goal for many years. Pursuit represents the actions we take to achieve this objective, which encompasses two aspects: one is theoretical research, and the other is transforming the results of our theoretical research into practice.

Perhaps the latter objective is more important than the former. Karl Marx once said, "The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it." We, the scholars of Chinese administrative law, also aim to change the world, to control the Leviathan, to tame it, and to cage it. The thirteen problems mentioned by Principal Ma just now is evidence that the Leviathan has not been under adequate control-- that it often runs loose. We have been working on this for forty years, and although the results are not particularly satisfying in this regard, there have also been significant successes; our efforts have not been in vain.

The “pursuit” I will talk about concerns two aspects: theoretical research and practical application. I will address six questions. The first question is: How did the field of Chinese administrative studies originate? This will primarily involve reviewing its history. I shall depend on the audience to elaborate on its future prospects. The second question concerns the development and promotion of administrative legislation in China. The third question is about how teaching and research have been comprehensively expanded. The fourth question delves into the changes brought about by the rise of administrative law in China. The fifth question focuses on the innovation of China’s administrative law concepts and systems in the New Era. These innovations may not be fully realized yet, but we are actively working towards them. The sixth and final question explores the experiences of the development of administrative law and the administrative rule of law. Given the limited time, I will only cover some key points

1. The Arduous Beginnings of Administrative Law Studies in China

[Group photo in the backyard of Professor Gong Xiangrui's home. From left to right are: Tao Jingzhou, Wei Dingren, Jiang Ming'an, Luo Haocai, Gong Xiangrui, Wang Shaoguang, Chen Xingliang, Li Keqiang, and Wang Jianping.]

The name of one man cannot be omitted from the inception of administrative law in China - Mr. Gong Xiangrui. He was the first person in China to propose "administrative law" as a legal department and "administrative jurisprudence" as a discipline. Mr. Gong's lectures were filled with passion and had a strong influence on his students. He was highly engaging and inspiring. My interest in administrative law was sparked during Mr. Gong's classes. I attended his lectures during my third year, and by my third and fourth years, I spent almost half of my time in the library, reading books on administrative law, including materials from the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. I also picked up a bit of English and read some English and American materials, even though I never formally studied English in college; my major was Russian. I taught myself the 26 letters of the English alphabet and gradually became able to read a bit. To be honest, I attribute my focus on administrative law mostly to his influence. During my freshman and sophomore years, I was more interested in economic law, as you can see from the translated articles I published; they were related to economic law, specifically Soviet and Eastern European economic law. It wasn't until my third and fourth years that I started to explore administrative law, all thanks to his influence. So, we must not forget this respected gentleman.

The second landmark in the inception of administrative law in China spans from 1982 to 1985, when Peking University, Beijing College of Politics and Law (now China University of Political Science and Law), and Southwest University of Political Science & Law gradually introduced selective courses in administrative law and compiled various study materials. All three of the universities compiled their respective materials. I was principally responsible for authoring the administrative law textbooks at Peking University, totaling seven books: this includes one book on administrative law, one on administrative studies, a three-volume selection on Chinese administrative law, and a two-volume selection on foreign administrative law. Compiling these took a considerable amount of time, during the second and third years of my teaching at Peking University.

The third landmark event during the inception of administrative law in China is the publication of "Outline of Administrative Law". It was the first comprehensive administrative law textbook after China's reform and opening up. Since the reform and opening up, there have been four generations of standardized administrative law textbooks. The first generation was embodied by "An Outline of Administrative Law," with 王珉灿 Wang Mincan as the chief editor and 张尚鷟 Zhang Shangzong as the deputy editor. 王名扬 Wang Mingyang played a pivotal role in the compilation of this book. He was the first scholar to earn a doctorate in administrative law from the University of Paris. Much of the material in the textbook was written by 王名扬 Wang Mingyang (1916-2008), who, despite not being the chief or deputy editor, had a significant influence on its content.

The fourth landmark was the publication of self-authored administrative law textbooks by scholars. In August 1985, I published "Studies in Administrative Law." Initially, I approached China's Law Press. But what is exactly administrative law, asked the editor, I had never heard of it; and possibly because I was only a teaching assistant at the time, the editor was uncertain about my ability to write a book, so it was put on hold. Consequently, I took my manuscript to Shanxi People's Press, where it was published. In December of the same year, Professor 应松年 Ying Songnian and Professor 朱维究 Zhu Weijiu co-authored "General Theory of Administrative Law," published by China Workers Publishing House. These two books were among the earliest individually authored textbooks by scholars after China's reform and opening up in 1978.

After 1985, administrative law courses became a common offering in the law departments of universities across China. Leading institutions like Peking University (PKU), Renmin University of China, Beijing College of Political Science and Law [now China University of Political Science and Law], Southwest University of Political Science & Law, Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Northwest University of Political Science & Law, and East China University of Political Science & Law, gradually transitioned administrative law from an elective to a compulsory subject, with PKU being one of the earliest to do so.

I was originally assigned to the Administrative Law Research Office. Professor 罗豪才 Luo Haocai, then the deputy director of the research office asked me what I wanted to specialize in, and I told him that I had no interest in Chinese constitution or foreign constitution studies. He suggested that I join the Editorial Department of Peking University Law Journal. I replied that I didn't want to become an editor; I wanted to work on administrative law. I chose to stay because I wanted to pursue a career in administrative law. So in 1987, PKU's Law Department established a dedicated administrative law teaching and research office, and I had the honor of serving as its first director.

During this period, some universities began admitting master's and doctoral students in administrative law. The first three doctoral students in administrative law were 马怀德 Ma Huaide from China University of Political Science and Law, 袁曙宏 Yuan Shuhong from PKU Law School, and 冯军 Feng Jun from Renmin University of China. These were the earliest doctoral graduates in administrative law after China's reform and opening up, and they each went on to make significant contributions to the field in China.

2. The Formulation of China's Administrative Laws

I will discuss three aspects regarding administrative law legislation: the drafting of the Civil Servant Law, the drafting of the Administrative Litigation Law and the State Compensation Law by the Administrative Legislation Research Group, and finally, the revision, abolition, and establishment of administrative regulations.

In 1984, the Organization Department of the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and the Ministry of Personnel [incorporated into the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security in 2008] formed a legislative team comprising 15 members to draft what later became the Civil Servant Law, initially known as the National Civil Servants Law. 曹志 Cao Zhi, Deputy Head of the CPC Central Committee Organization Department, who would later become the Vice Chair and Secretary-General of the National People's Congress (NPC) Standing Committee, invited five scholars to the group. These scholars included 杨柏华 Yang Baihua from the China Foreign Affairs University, 皮纯协 Pi Chunxie from Renmin University, 张焕光Zhang Huanguang from the Law Institute of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, 袁岳云 Yuan Yueyun from the Institute of Political Science of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and myself. I had recently graduated in 1982 and continued to work as a teaching assistant at Peking University. I had just graduated in 1982 and continued to work at the university. They knew I specialized in administrative law, I attended one of their meetings, and I had written a paper on national civil servants law. So, they contacted Peking University's personnel department and invited me to join, which was a remarkable opportunity for me.

When I was at Peking University, as a Southerner, I had limited access to regular rice, with just six kilograms per month. However, when I joined the legislative group, I had rice available every day. Moreover, I had never tasted yogurt before, but it became a daily part of our meals. We stayed in a small villa, which had previously accommodated Zhou Yang. The treatment and conditions were truly excellent. There were 15 of us in the group, and we were treated exceptionally well. Both the CPC Organization Department and the Ministry of Personnel attached great importance to our work. Even bureau chiefs would stand in the background, while we five scholars and Deputy Head Cao Zhi sat at the forefront.

During that period, there were no existing laws regarding civil servants. We had a heap of documents, including two compilations of personnel work documents for every year, which were quite substantial. However, these documents alone couldn't serve as a basis for drafting the Civil Servant Law. We needed to look into existing legal frameworks.

During this time, the CPC Central Committee Organization Department sent letters to all Chinese embassies worldwide, requesting that they send information about their respective countries' civil servant laws and how these laws were implemented within two months. This proactive approach showcased the Organization Department's significant influence. We received a substantial stack of materials in response. Our work routine involved reviewing these documents in the morning, drafting provisions in the afternoon, and engaging in collective discussions in the evening. After approximately six months of dedicated effort, we completed the draft of the law. However, it was not immediately enacted. It wasn't until 1993 that the 《国家公务员暂行条例》 "Interim Measures for Civil Servants of the People's Republic of China", which was drafted by us, got officially promulgated. Elements such as the requirement for civil servants to take exams, undergo evaluations, and be subject to transfers - essentially, the entire civil servant system - were crafted by our team. Subsequently, in 2005, the 《公务员法》" Civil Servant Law" was enacted based on the foundation we had established. Our work was significantly informed by practices from around the world.

The second point I will address is the Administrative Legislation Research Group. After the passage of the "General Principles of the Civil Law of the People's Republic of China" in October 1986, the National People's Congress organized a symposium. Mr. 陶希晋 Tao Xijin spoke at the meeting, that China had established the "Criminal Law", the "Criminal Procedure Law", "Civil Procedure Law (trial)", and the "General Principles of Civil Law." He said that among the "Six Codes", only the "Administrative Law" and the "Administrative Litigation Law" are missing. We should develop these to improve China's legal system.

At the time, 彭真 Peng Zhen served as the Chair of the NPC Standing Committee, and 王汉斌 Wang Hanbin was the head of the Legislative Affairs Commission of the NPC Standing Committee. Respecting Mr. Tao's seniority, Wang encouraged him to lead the initiative. Wang Hanbin later reported to Peng Zhen to discuss setting up a legislative group under the Commission, to be organized by the esteemed Mr. Tao. Mr. Tao invited my mentor, Mr. Gong Xiangrui, and I was also brought along. Mr. Tao said that since China is going to work on administrative law, you professors needed to start writing and generating publicity on the matter.

After returning from Mr. Tao's place, Mr. Gong instructed me to draft the initial text, which he would review. 齐一飞 Qi Yifei, then Secretary-General of the Beijing Municipal People's Congress, was tasked with media relations. The three of us formed a small team; I was responsible for drafting the documents, Mr. Gong was in charge of reviewing and revising them, and Qi Yifei was responsible for submitting them to newspapers and magazines for publication. We first published an article 《要制定做为行政基本法的行政法》"We Shall Establish Administrative Law as a Fundamental National Law," in the Guangming Daily; then second, "Strengthen the Development of China's Socialist Administrative Law," was published in 《中国法制报》"China Legal System" (now 《法治日报》Legal Daily); and the third, "On the Basis and Judicial Review Authority of People's Courts in Adjudicating Administrative Cases," also in the "Guangming Daily."

However, it was not enough to just create public discourse for the development of administrative law. As in the words of Karl Marx, “philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.” Thus, the Administrative Law Legislative Research Group was established with Jiang Ping, then Principal of the China University of Political Science and Law and deputy head of the Legislative Affairs Commission of the NPC Standing Committee as the group leader. Luo Haocai and Ying Songnian were deputy leaders, and a total of 14 members including myself, Pi Chunxie, Zhang Huanguang, Zhu Weijiu, Xiao Min from the National People's Congress Law Committee, Fei Zongyi from the Economic Court of Supreme People's Court (there was yet to be an administrative court), and Gao Fan from the State Council's Legislative Affairs Office made up the whole team.

Initially, the group drafted the "General Principles of the Administrative Law of the People's Republic of China." After six months of working at the hotel of the General Office of the State Council near Beijing Zoo, we produced a pile of drafts. But then we realized that the scope was too broad, encompassing administrative organization law, civil servant law, administrative penalty law, administrative licensing law, administrative coercion law, administrative reconsideration law, administrative litigation law, etc. It was unmanageable to include so much, and we could not proceed.

At that impasse, it coincided with the NPC's amendment of the "Civil Procedure Law (trial)." The initial draft of the "Civil Procedure Law (trial)" had a chapter on administrative litigation. Later, it was argued that the concept of administrative litigation was unclear, so it was reduced to a single article, which is Article 3 of the "Civil Procedure Law (trial)": The People's Court shall conduct administrative cases in accordance with civil procedure.

Two options were available for the amendment of this article: one was to dedicate a chapter to administrative litigation within the "Civil Procedure Law," and the other was to draft a separate "Administrative Litigation Law." Jiang Ping said, "Let's work on a separate 'Administrative Litigation Law.'" Since we were facing difficulties in progressing with our General Principles of the Administrative Law, we decided to shift our efforts towards drafting the Administrative Litigation Law.

As a result, in 1989, the "Administrative Litigation Law" was officially promulgated; afterward, the group drafted the "State Compensation Law" in 1994, the "Administrative Penalty Law" in 1996, the "Administrative Review Law" in 1999, the "Legislation Law" in 2000, the "Administrative Licensing Law" in 2003, and the "Administrative Coercion Law" in 2011.

To ensure the quality of legislation and draft these laws effectively, we conducted research overseas for several months and in more than a dozen provinces and cities in China. Additionally, we visited numerous countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Italy, to investigate how they handled administrative litigation laws. I had the opportunity to engage in academic discussions in many places during this period.

The third point I want to address is the promotion of reforming and replacing certain unlawful regulations with new ones. One example is the 孙志刚 Sun Zhigang case, which ultimately led to the abolition of the Measures for Internment and Deportation of Urban Vagrants and Beggars. The three of us wrote letters to the National People's Congress about it. At that time, 曹康泰 Cao Kangtai was the director of the State Council Legislative Affairs Office, and he also invited us to discuss the matter. I suggested that the management of shelters shouldn't be limited to government operations and that some organizations, including non-governmental and non-profit organizations, should also be allowed to operate them. Although my suggestion was not adopted, I still believe it was a valid point because relying solely on government-run shelters posed several problems. The Measures for Internment and Deportation of Urban Vagrants and Beggars were later amended into the 城市流浪乞讨人员救助管理办法 Measures for the Administration of Relief for Vagrants and Beggars without Assured Living Sources in Cities which marked significant progress.

The second incident was the 唐福珍 Tang Fuzhen case. Several professors from Peking University, including Shen Kui, Wang Xixin, Chen Duanhong, Qian Mingxing (who specialized in civil law), and myself, submitted a petition to the NPC Standing Committee, requesting a review of the regulations on urban housing demolition and resettlement. This was due to numerous deaths, suicides, and self-immolations related to forced demolitions at the time. We insisted on repealing the unjust 《城市房屋拆迁条例》" Urban Housing Demolition Regulations." Xing Chunying [then Deputy Director of the NPC Legislative Affairs Commission] talked to us and called the State Council Legislative Affairs Office, saying that the professors had objections, and they promptly abolished the regulation themselves. Instead, they introduced the 《国有土地上城市房屋征收补偿条例》"Regulations on Expropriation and Compensation for Urban Land," which is the current regulation we often refer to for analysis.

Another case was the "Reeducation through Labor" system, involving 唐慧 Tang Hui. Her daughter had been raped, and she went to petition for justice. However, she was detained and sent to a labor camp. This case is also discussed in my book "Research on ‘The Three Administrative Laws’." [The Three Administrative Laws refer to The Administrative Penalty Law, The Administrative Licensing, and The Administrative Compulsion Law.] Later, People's Daily Online awarded each of us five individuals a large trophy, presenting us with the award of "Top Ten Responsible Citizens." [in 2009]

3.Comprehensive Development of Teaching and Scientific Research

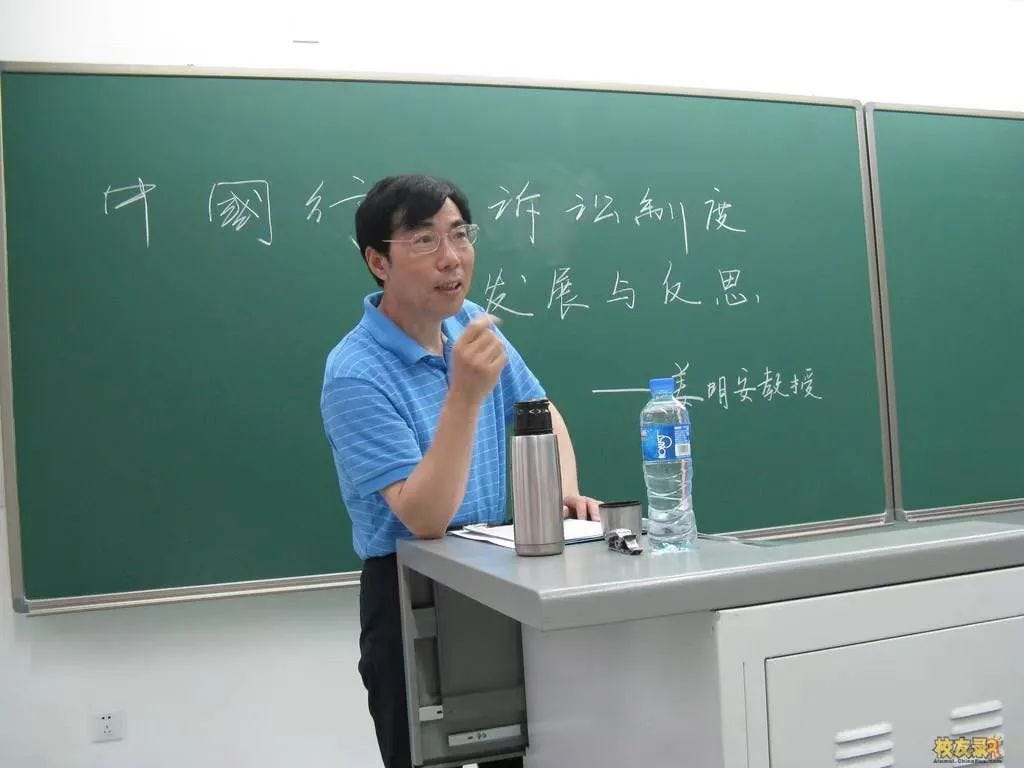

[Professor Jiang Ming'an teaches at Peking University Law School]

I want to address five landmarks in this regard. Firstly, since the mid-to-late 1980s, administrative law courses have been widely introduced across universities under the Ministry of Education, Party schools at all levels, and administrative colleges, with many institutions making it a required subject.

Secondly, the 中国行政法学研究会 Chinese Society of Administrative Law was established, and the first council of 27 members was elected. 张尚鷟 Zhang Shangzong served as the council leader, with 罗豪才 Luo Haocai and 应松年 Ying Songnian. I was the youngest member of that council, and today, fewer than five of us are still alive.

Thirdly, the Supreme People's Court and Peking University jointly established an advanced program for senior judges. This program, which ran for four terms, was attended by judges from the intermediate people’s courts who were chief justices of the administrative law division or deputy presidents of their courts and above. In collaboration with the Supreme People’s Court, they were trained in administrative law and economic law by the PKU, and criminal law and civil law by Renmin University. There was also a program for teachers at China University of Political Science and Law. Just a few days ago, we had a gathering of those senior judges who are now mostly in their 80s, and sadly, many have passed away. They came from all over the country to attend the event. The program for senior judges made significant contributions to the development of administrative litigation in China. Each term trained 60 people, totaling 240 judges across four terms. The practice of administrative litigation in China gradually took shape through these individuals.

Fifthly, textbooks on administrative law were compiled. The first generation of standardized textbooks was the previously mentioned "Outline of Administrative Law," and the second generation was the "Administrative Law" edited in 1989 by Professor Luo Haocai and vice-edited by Professor Ying Songnian, of which I was one of the authors; the other three authors were 皮纯协 Pi Chunxie, 张焕光 Zhang Huan’guang, and 朱维究 Zhu Weijiu. The third generation of standardized textbooks was "Administrative Law and Administrative Litigation Law," which I edited in 1999. It is now in its seventh edition and the eighth edition is about to be published. The fourth generation of standardized textbooks was within the state Marxist theory Research and Building Project published in 2018, with Professor 应松年 Ying Songnian as the chief editor and 马怀德 Ma Huaide and me as deputy chief editors, which has been published in two editions. Nowadays, both the third and fourth generations of standardized textbooks are still in use.

4.The Impact of Administrative Law on China

The fourth topic I’m going to address today is the impacts and changes brought about by administrative law in China, which can be summarized in five main aspects:

The first aspect is the change in the mindset of the Chinese people, which includes three significant shifts:

First, the traditional belief that "the people's government is inherently correct and acts in the interests of the people" is gradually shifting towards the understanding that "the people's government can make mistakes and infringe upon the rights of the people. Therefore, its power must be regulated by law to prevent it from transforming into the Leviathan."

Second, the concept of the relationship between officials and citizens as akin to "parent-officials" and "subjects" is evolving into a view of "public servants" and "masters," where public servants can only act with legal authorization, and citizens are free to do anything that the law does not explicitly forbid; not the other way round.

Third, the old notion of "citizens do not sue officials" or "citizens do not contend with officials" has changed to "citizens can not only sue officials but can also win against them," embracing the principle that “power comes with responsibility; the exercise of power requires oversight, official violations of the law entail lawsuits, and any infringement upon rights must result in compensation.”The latter principle, except for "violations of the law," which is my own input, was originally proposed by Premier Wen Jiabao and incorporated into the《全面推进依法行政实施纲要》 Program for Comprehensively Promoting “Administration by Law”. It is indeed a very valuable summary.

The second aspect is the significant transformation in governance methods, which mainly includes four points:

First, the operations of administrative agencies and their staff have shifted from following directives, orders, and official documents from higher authorities to adhering to the principle of administration according to law.

Second, the methods of administrative management have moved from being unilaterally coercive to placing greater emphasis on participation and interaction.

Third, the means of administrative enforcement have evolved to primarily regulation, also incorporating flexible approaches like administrative agreements and guidance, as well as soft tactics.

Fourth, administrative activities have transitioned from prioritizing speed and efficiency to giving greater attention to the due process of law and the protection of the rights and interests of administrative subjects.

The third aspect is the significant changes in the objectives of the CPC, mainly in three respects:

First, the Party has shifted from being guided by the policy of taking class struggle as the main line and the singular pursuit of GDP growth and economic and material development to also striving for fairness and justice, and the advancement of social, ecological, and political civilization. In total, five civilizations have been proposed, and of course, those of us working in the field of administrative law are not the sole contributors.

[The five civilizations are material, political, cultural-ethical, social, and ecological civilizations. The concept was first proposed in Xi’s 2021 speech at the centenary of the CPC as a testament to“a new and uniquely Chinese path to modernization, and created a new model for human advancement.”]

Second, there has been a gradual transition from ruling the country primarily through policy to governing according to the rule of law.

Third, there has been a move away from an excessive focus on order and "stability maintenance" towards a greater emphasis on the protection of human rights and the lawful rights and interests of citizens, legal persons, and other organizations. The Party changes. Everything does. But what remains unaltered and unalterable is the imperative to cage Leviathan and tame Leviathan.

Ideological innovation can be categorized into five main aspects.

The first aspect concerns the concepts of 以人为本 “people-based approach” and 以人民为中心 “people-centered approach”. The "people-based approach" was emphasized during Hu Jintao's era, and it's a valuable concept. Of course, the "people-centered approach" also implies prioritizing people, but there are subtle differences between the two. Just as Chairman Mao said, “Our Communist Party and the Eighth Route and New Fourth Armies led by our Party are battalions of the revolution. These battalions of ours are wholly dedicated to the liberation of the people and work entirely in the people's interests.” However, many people later lost sight of their original intentions and drifted away from serving the people. They shifted their focus to class struggle and GDP growth.

The second aspect involves “putting power in an institutional cage”, or, as I mentioned earlier, caging the Leviathan.

The third aspect is the principle of transparency, with exceptions for non-disclosure.

The fourth aspect encompasses emergency legal systems to address risks in society. We have included this aspect in our standardized textbooks, which was not previously covered.

The fifth aspect involves the deep integration of informatization and the rule of law.

There has been a multitude of institutional innovations, and I'll provide 10 examples:

1. The Three Lists: 权力清单 Powers List, 责任清单 Responsibility List, 负面清单Negative List.

2. "Without a second trip" policy, which enhances online data connectivity to reduce the efforts citizens have to make for government services.

3. "Board the Bus Before Buying the Ticket" practice [e.g. the transition from an approval-based system to a direct registration system], based on Shanghai's experience.

4. Random selection of inspectors and inspection targets and the prompt release of results. This practice originated in Shenzhen.

5. Public hearings, including administrative action hearings and hearings for administrative decision-making, legislation, and normative documents. Note the difference between the two and the innovative value they both present. When we were drafting the rules on public hearings for the Administrative Penalty Law, many colleagues opposed the idea, including members from the NPC Legislative Affairs Commission. They questioned the concept of public hearings, arguing that we should adhere to the principle of serving the people and wondered why we were trying to introduce public hearings. However, later on, Professor Luohao Cai said that we should look forward, and that hearings were indeed a very positive and beneficial practice.

6. Legitimate Expectations, as initiated by the Administrative Licensing Law, and later extended to regulations aimed at optimizing the business environment. [The doctrine protects a procedural or substantive interest when a public authority rescinds from a representation made to a person]

7. The "Five-Step" approach to administrative decision-making, which includes public participation, expert review, risk assessment, legality review, and collective deliberation by a leadership team. Major decisions now require meetings for review and approval, avoiding scenarios like the former Minister of Railways, Liu Zhijun, who unilaterally approved large projects worth hundreds of millions yuan to a businesswoman [Ding Yuxin]. Now both of them are in jail.

8. The three major administrative law enforcement systems: public notification of administrative law enforcement, a recording system throughout the whole process of law enforcement, and a legal review of major law enforcement decisions.

9. The relative concentration of administrative law enforcement powers. In contrast to the current collaborative and integrated law enforcement efforts, previously, the opening of a restaurant would attract, say, the Bureau for Industry and Commerce [ which was incorporated into the Administration for Market Regulation in 2018] on the first day, and different regulatory agencies on every subsequent day, causing disruptions to business operation. Now, only one government department is allowed.

10. Substantive resolution of administrative disputes [which not only facilitates a settlement between the parties but also traces back to the root cause, leading to institutional adjustments, effectively preventing potential administrative disputes from arising]. It is a recent development involving institutional innovation.

These examples showcase the breadth and depth of institutional innovations in China.

5. Experiences and Lessons from Administration by Rule of Law

The last topic for today is the lesson from administration by the rule of law, for which I have summarized six main points:

Firstly, adhere to the path of combining China's characteristics with lessons from others.

This approach emphasizes not only China's national circumstances but also the importance of learning from mature experiences abroad. While addressing issues in China, it is crucial to consider our unique characteristics, but it is equally essential to draw from the well-established practices of other nations. It's like crossing a river: if someone else has already built a bridge, it is unnecessary to insist on wading through the water and feeling for stones to cross; some solutions have already been discovered. Learning from the experiences of others and stepping on stones that have already been felt is a valuable approach.

Secondly, closely integrates administrative legal theory and the practice of building administration by the rule of law.

Be bold in exploration, yet strengthen theoretical guidance to grasp the direction and goals of exploration -- this is of paramount importance. The drafting of administrative laws always involved two or three fields and agencies. The first legislative group for Civil Servant Law had five scholars from academia, me included, and another ten from the CPC Organization Department and then the Ministry of Personnel. The second legislative group for the Administrative Litigation Law had members from the NPC Legislative Affairs Commission, the Supreme People's Court, and the Legislative Affairs Office of the State Council, all closely collaborating with one another. This is the China experience.

Thirdly, promote the establishment and improvement of administrative action and administrative procedure laws through the "citizens suing officials" system of administrative litigation.

The general practice for rule of law is to start with Administrative Organization Law, then Administrative Action Law, followed by Administrative Litigation Law and the Administrative Relief Law.

However, we did it in reverse order, starting with the Administrative Litigation Law. Prof. Jiang Ping, head of the legislative team for Administrative Litigation Law, did an admirable job of putting administrative agencies in the hot seat. When administrative counterparts sued administrative agencies in court, the question arose: on what basis should the agencies act lawfully if there is no law? This lack of legislation compelled the legislative body to enact laws such as the Administrative Penalty Law, Administrative Licensing Law, Administrative Coercion Law, Land Management Law, Food Safety Law, and Drug Administration Law. Many administrative act laws in China were formulated under such pressure.

The next step concerns the clarification of the powers of administrative agencies, which were set to be defined by internal "Three Determinations" schemes [to determine and publicly release the division of responsibilities, internal organizational structure, and staffing arrangement]. However, the "Three Determinations" are not laws but an administrative task under the charge of the 编办 State Commission Office of Public Sectors Reform (SCOPSR). So when someone accuses an administrative agency of exceeding its authority, the "Three Determinations" cannot be cited as a legal document for administrative responsibilities. This prompted the need for an Administrative Organization Law. Of course, this will take many years, perhaps a decade or two. I was originally involved in the formulation of three regulations by the SCOPSR, but none of them have been enacted yet. This project will definitely be resumed in the future.

Fourthly, promote standardization of specific types of administrative acts through the formulation of specific administrative laws in different fields and regulations, thus leading to the compilation of a unified administrative procedure code or basic administrative law code.

China's experience in administrative law legislation involves initially drafting laws such as the Land Management Law, Pharmaceutical Drug Administration Law, Food Safety Law, etc.; the second step is to compile codifications for various types of administrative actions rather than administrative actions specific to particular fields, such as the Administrative Penalty Law, Administrative Licensing Law, Administrative Coercion Law, etc. This is followed by the development of a unified administrative procedure code or basic administrative code. I have been trying to advance the Administrative Procedure Law for over twenty years; I hope this will be on the agenda of the next NPC and not of the next generation.

Fifthly, focus on specific cases to break through the obstacles to the development of the rule of law in specific fields and take the opportunity to push forward the rule of law in these areas.

Administrative law scholars have seized cases of Sun Zhigang, Tang Fuzhen, and Tang Hui, etc. to reveal the shortcomings and malpractices of the rule of law and promote it. We centered on those cases and facilitated public opinion. In the end, administrative regulations were abolished, and new laws that were conducive to the protection of citizens' rights were enacted, moving the rule of law forward. This is also an important experience that needs to be continued in the future, but it is important to choose truly typical cases for breakthroughs.

Lastly, testing before promoting the development and innovation of the administrative law systems.

Pilot programs ensure that development and innovation are prudent. Some matters can't be legislated quickly, but administrative regulations and local regulations can be trialed first. Starting locally before moving to the central level allows for local reforms to inform and accumulate experience for central legislation; initiating administrative legislation before legislation by the People’s Congress [China's legislature] similarly builds a foundation of experience. This approach is another important experience in promoting the rule of administrative law.

[Professor Jiang Ming'an during his lecture at Shue Yan University in Hong Kong.]

Caging the "Leviathan" is the dream and pursuit of Chinese scholars on administrative law. For this, we have been exploring for forty years, but we are still far from our original dreams and goals and need to continue our efforts. Democracy and the rule of law have not yet been realized and we must continue to strive!

Thank you for listening!

Pekingnology has uploaded the full, Chinese-language speech to Google Drive.

A Unique Window into Huawei

Perhaps one of the least-known facts about the world’s most scrutinized company is that, for years, Huawei has kept its forum for employees open to the public. The 心声社区 Xinsheng Community, offering some of Huawei’s corporate memos and founder’s internal speeches, sets the Chinese employee-owned company apart from fellow

Very interesting, thank you. It seems to me that China is going through a flourishing of administrative which Australia went through about 50 years ago. When I studied law in Melbourne in the mid 1980’s I recall my professor of Administrative Law say that the expansion of Australian administrative law (achieved in part by legislation and in part by judicial activism) was the most important development in Australian law. Personally I don’t think it was that radical a change, but it did lead to people being able to hold bureaucrats accountable for decisions. The most important aspect of it was the establishment of an Administrative Tribunal dedicated to giving citizens a relatively low cost process for reviewing administrative decisions made by government departments and Ministers.

To me, Administrative Law can be summarised as two basic principles of “natural justice”: first, an obligation of due process, such as giving people affected a right to be heard before making decisions that affect them. Second, a requirement for impartiality. The decision-maker must not have a personal interest in the outcome of the decision.

The Administrative Tribunals were different from courts in that the Tribunal could make decisions “de novo”, whereas courts could only review an administrative decision. If a court found the decision was flawed, it had to be sent back to the decision-maker to decide the matter again. But the Tribunal had the power to make the decision themselves. Not just direct the decision-maker to review their decision.

Be wary, Confucius was more clued in than we might recognize today, that a procedural system can be played(and in the case of the USA was played) to favor the 1% over the majority, i.e.: he with the gold is who hires the lawyers and lawmakers. It can be come ceremony (礼)with out humanity (仁)。 This is doubly true in settler-colonial projects like Australia, Israel, and the USA; each held up as symbols of democracy when they are anything but; rather brutal exploiters of their spheres of influence.