Journalists’ Day Shouldn't be a Celebration

An industry that is, to say the least, drowning in clickbait, fake sentiment, and traffic-worship needs resuscitation — not institutional narcissism or self-mythmaking.

November 8 is China’s state-anoited Journalists’ Day. Here is a reflection by an industry veteran who won the state-run China Journalism Award eight times in his two-decade career.

Cao Lin is now a professor at the Journalism and Information Communication School of Huazhong University of Science and Technology in Wuhan. Before returning to his alma mater, Cao was an in-house commentator of the influential China Youth Daily, later taking the helm of the newspaper’s commentary section.

A prolific opinion maker, he continues to write his 吐槽青年博士 blog within WeChat. He published the following commentary on November 8, 2025.

少说假大空,用硬新闻去提高社会能见度

Say Fewer Empty Words; Use Hard News to Improve Society’s Visibility

Journalists’ Day always compels a few words. I’ve seen a lot of chicken-soup posts gilding journalism, the reporter profession, and the media industry—some are self-moved, some overly exalted and sentimental—and it’s uncomfortable. The crisis faced today by the journalism major, the profession, and the media industry is visible to the naked eye. Journalism as an academic major is being talked down. Traditional media has fallen into a kind of “stagflation”: content looks more and more abundant, convergence forms are all flashy—videos, metaverse—information is getting inflated, reporters are getting more exhausted, incomes are falling, and the influence of media news content is declining. In many public incidents, people rely even more on personalized sources than on mainstream media. In this crisis of journalism, sentimentality is shameful, self-moved self-consolation is pathetic and contemptible.

Last year, I attended a professional seminar somewhere. Inside the seminar, media people were still talking about traffic—tens of millions, billions, viral hits, screens covered, how many shares, and so on. During a break I went to the restroom and overheard two colleagues from newspapers chatting. One asked: “Does your newspaper still publish?” The other sighed: “Ah, whether we publish or not—what’s the difference?” That restroom dialogue shocked me. First, colleagues don’t even know whether the other person’s newspaper still exists. Second, “what’s the difference?”—a powerless self-mockery born of a lack of confidence in one’s own content. That restroom exchange was real and cruel. Newspaper people must strengthen themselves.

In a discourse where journalism is universally talked down, I still insist: doing media and doing news requires working hard, through high-quality content, to rebuild confidence. Whether a newspaper exists or not makes a huge difference. Whether news exists or not makes a huge difference.

On Journalists’ Day, in a context where the news industry faces massive shocks and challenges, there should be sincere reflection on issues of survival—less empty rhetoric, less sentimental chicken soup. Don’t live inside some imagined, illusory, self-deceiving career makeup ritual and poster-style narcissism. Whether media and news exist should make a huge difference—one that is visible and tangible—not a silent death unnoticed by anyone.

A few days ago, I read a study by a professor in the accounting department at Peking University’s Guanghua School of Management, titled “Local Newspaper Closures and Bank Loan Contracts.” The paper analyzed data from 26 U.S. local newspapers that shut down between 1991 and 2016, collecting a unique sample of 6,842 loans, innovatively focusing on the impact of local newspaper closures on bank lending to local firms. The research found that after local newspapers disappear, local firms’ bank loan spreads increase by an average of about 30 basis points.

What causes this connection? The chain-reaction problems created by a “news desert” lacking local reporting. Local media report two categories of information that other media rarely touch: first, non-financial information about firms—such as whether companies pollute the environment, or have labor disputes and other negative news. Second, information on local public policies and the social-political environment. On these two types of information, local newspapers conduct in-depth reporting with first-hand details. These are not things you can casually search and fine online; they require local reporters to squat on site, conduct deep interviews, and dig out information—crucial for banks judging corporate risk.

When local media, local news, scrutiny of government power, and in-depth analysis disappear, banks are unable to obtain real information about companies and can only protect themselves by raising financing costs.

Whether there are newspapers and whether there is news makes a huge difference—it can directly affect the cost of corporate loans. This is just one snapshot. News reporting covers every aspect of society, with enormous impact. When local print media disappear, loan costs rise. The function media and news serve is to “increase society’s visibility”—that is precisely why people trust and rely on news and journalists: through professional contribution, making this society more transparent.

Journalism is a profession built on the pursuit of objectivity, belief in truth, a public-interest orientation, and the transparent dissemination of information. The ideal of journalism is the ideal pursuit of information transparency.

In WeChat Moments, there is a setting called “visible for three days.” It carries rich metaphor. Society also hides a “three-days-visible” mechanism—many areas erect barriers preventing the public from seeing: corruption that hides itself, press spokespeople who become “press-non-spokespeople,” monopoly-constructed information black boxes, marketing and advertising brainwashing, prejudice and obsession sealing off minds. These barriers to “seeing transparently” require reporters’ curiosity and excavating power to break—to break through the frozen and the slick, to refuse to accept the world’s mere surface.

Isn’t that so? Every effort media and journalists make—the honor of this profession—lies precisely in raising society’s visibility in public affairs: seeing Arctic Catfish scandal, seeing Ms. Dong, seeing the chain of problems after lead poisoning, seeing drowned-out voices, seeing the hidden pain of persons with disabilities, seeing the towering character of the teacher who lent her own rib as a torch for students in the mountains, seeing the safety issues behind the smart-tech bubble. Helping the public extend its eyes and ears. When livestreamers, hype, and marketing push unthinking action, journalists use “facts dug out” to build a blocking mechanism, giving people the ability to say no to anything handed to them.

What deserves reflection is that the crisis facing news and journalists is precisely a crisis in “using high-quality content to raise society’s visibility.” News has been abandoned by the public at times, because it not only failed to improve visibility, but even reduced visibility.

First, the flood of “headline corruption.” Headlines are the eyes of media. The quality of a media outlet’s headlines most directly reflects its transparency and sincerity in improving society’s visibility. What disgusts the public is that mainstream media has led a very bad trend: suspense-bait headlines, obstacle headlines, blind-box headlines, manufacturing information black boxes, greasy and slick, lowering transparency and sincerity. “Today, Jiangsu officially enters…” “The new head coach of China’s national football team is… him!” Forcing people to click just to give them a bit of pitiable traffic. “Shao Jiayi appointed national team head coach” is transparently clear at a glance, whereas “The new head coach is… him!” lowers visibility. Open some mainstream media apps—such headlines are everywhere. They cheapen the media, cheapen news, and overdraft the public’s trust in mainstream outlets. Obstacle and blind-box headlines aren’t merely blind boxes—they are information corruption: hiding key facts to blind the audience, putting traffic above transparency and the right to know.

Second, the flood of “speech corruption.” I analyzed this in an earlier article. Some articles’ sentences have neither subject nor object, just waves of adjectives and verbs, exhibiting a kind of abstract busyness—detached from reality, sincerity, and truth. They ignore real people and real life, and only ask about abstractions. Riding a “sentimental paper airplane” fluttering in the air without landing. Lush rhetoric building sentimental prose is language corruption decorating emotional corruption. Professor Lü Dewen of Wuhan University wrote an article, “Investigation and Research Must ‘Think About Things,’ Not ‘Think About Words.’” He argues that research must have clear problem-awareness, cannot invent problems out of nothing, cannot use big, abstract concepts and “big words” to drown out concrete phenomena. Yet current news corpuses are filled with “big words.” “Leading” is no longer enough; it inflates to 遥遥领先 “leading by a large margin,” then stacked into 清场式领先 “sweeping-field leading,” 清场式遥遥领先 “sweeping-field leading by a large margin,” 断代式领先 “generational-gap leading.” Beautiful big words do not bring transparency—they drown facts, corrupt the quality of Chinese thought, and create confusion and endless dispute.

Third, the flood of “visualization corruption.” This seems paradoxical. Isn’t visualization meant to let people see and see clearly? Videos, pictures, integrated media—aren’t they supposed to make news more transparent? On the contrary, many forms of visualization create covering and black-box effects. True visualization should center on “public visibility,” not on converting one’s own traffic. In this so-called flashy fusion of images and videos, public attention becomes a commodity: not “what matters to the public becomes more visible,” but “what can be converted into traffic becomes highlighted and monopolizes attention.” The formerly proud idea of “influencing those with influence” has degenerated into “influencing those who are easily influenced” and “influencing those who can be monetized.” Visualization no longer serves the public interest but centers on traffic, treating public attention as a kind of fuel. In this kind of visualization, trivial fluff dominates trending lists, doubled in visibility, while issues crucial to the public lack the visibility they deserve.

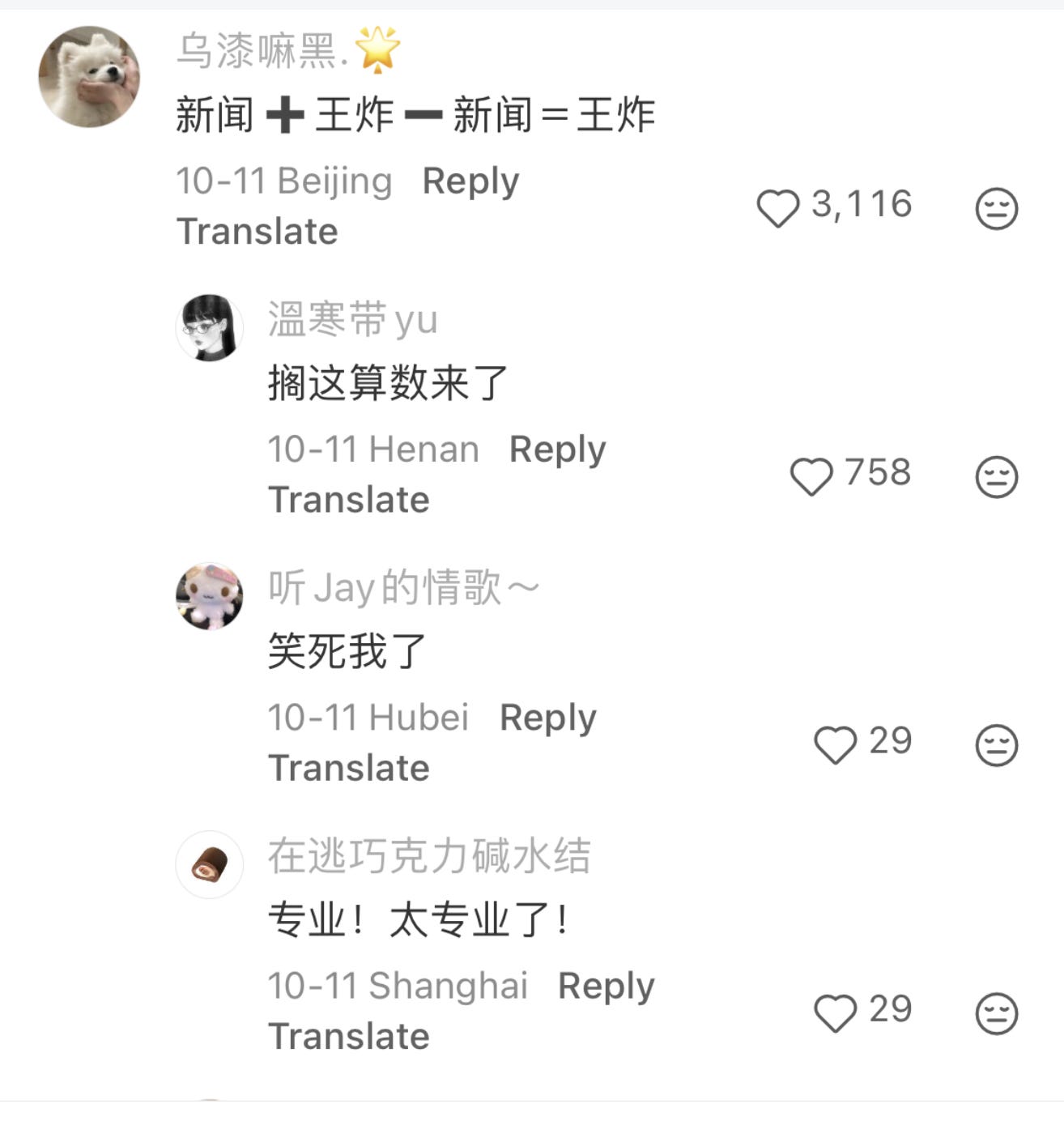

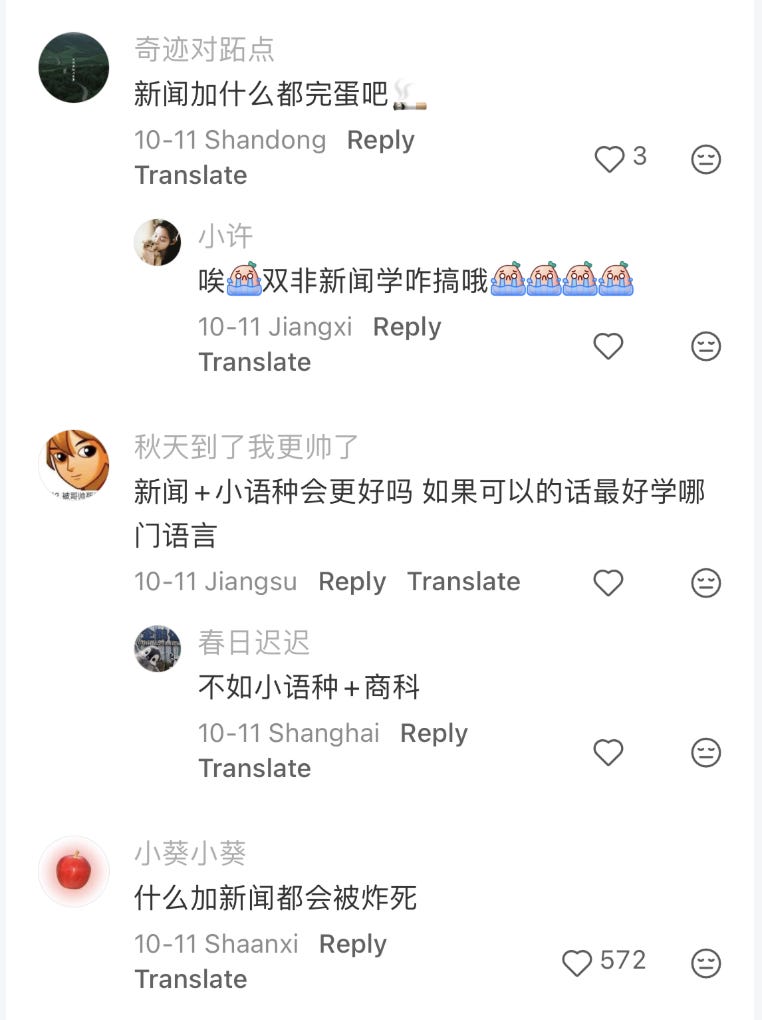

Look at how netizens on social media mock the journalism major —it’s embarrassing: “Journalism + trump card major — journalism = trump card.” [Zicen’s note: A student asked: “I’m already majoring in journalism. What additional major should I combine it with to make it a career ‘trump card’?” The top-liked reply was: “Journalism + trump card — journalism = trump card.” In other words: why bother with journalism at all? Just study the ‘trump card’ major directly. The joke implies a brutal message: journalism adds no value — it’s useless.] Those jokes on Xiaohongshu/Red Note aren’t funny.

In this profession, the thing we do most often is to tell others never to enter this profession. A sunset industry that only moves itself and a handful of people into self-indulgent excitement. A veteran reporter once said he had trained four interns — and successfully extinguished every one of their journalistic idealism

As someone who works in news, teaches news, and studies news, I really dislike this defeatist, toxic chicken soup. But seeing the massive challenges facing journalism and the journalism profession, it is hard to mount a strong defense. When we cannot produce more work that increases society’s visibility, it is easy to lower our heads before such ridicule.

On Journalists’ Day, we cannot entertain ourselves. We must measure our work with the ruler of “society’s visibility.” As the ears, eyes, and mouth of society, have our works made the world more transparent? Have we made facts, truth, and reality visible in public events?

Keep going. With our feet, our brains, our eyes, and our pens—let’s work together to improve this world’s “social visibility”!

One form of journalism practiced by self-employed individuals these days

Important points. But adversarial and confrontational journalism needs systemic and institutional protection AND an audience that thinks its output matters. This is not just a challenge for China to reckon with…