Li Wenliang, an Ordinary Man (2020)

Lest we forget

It’s been six years since Dr. Li Wenliang passed away in Wuhan.

普通人李文亮

Li Wenliang, an Ordinary Man

Published in 人物 People on February 7, 2020

by 罗婷 Luo Ting, 杨宙 Yang Zhou, and 罗芊 Luo Qian

Edited by 糖槭 Tangqi

Last night at 11 p.m., when a People reporter arrived at the inpatient building of the Houhu campus of Wuhan Central Hospital, two of Li Wenliang’s university classmates had already been waiting there for half an hour. They were also doctors in Wuhan, sent by their entire class to see him. But visiting hours were already over, and the entrance to the inpatient building had been blocked off—they couldn’t get in.

It was late. The building was still brightly lit. The second floor was the ICU where Li Wenliang was being resuscitated. Several floors above, his parents—also infected with COVID—were hospitalized as well. His classmates were worried about them and called Li Wenliang’s father, hoping they could go upstairs to keep him company. But hospital staff were with his father and refused the request over the phone. Later, they spoke with Li Wenliang’s pregnant wife, who was out of town. She was anxious and worried but didn’t know the latest information. They told her, “If there’s any news, we’ll call you the first moment we hear it.”

Just after midnight, the hospital was still continuing its efforts to save Li Wenliang. But a nurse from inside the building—dressed very lightly—came down alone to the first floor and burst into tears. First, she leaned against the wall crying; then she crouched on the floor and cried. Even from more than ten meters away, her sobs were clearly audible, echoing through the quiet hospital in the middle of the night.

His classmates talked about Li Wenliang’s condition. A few days earlier, Li Wenliang had given a media interview and seemed to be in good spirits. But in fact, for more than ten days, he had never been taken off a ventilator. One classmate said, “That was already a very bad sign.”

Yesterday afternoon, Li Wenliang was transferred from the Nanjing Road campus of Wuhan Central Hospital to the Houhu campus. According to this classmate, the reason was that he now needed ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation), but the Nanjing Road campus didn’t have it—their equipment had all been reassigned to Jinyintan Hospital. The Houhu campus still had one machine, which could save his life. There was also another version circulating online, saying that this ventilator was borrowed from another hospital.

Had his condition really deteriorated to the point of needing extracorporeal support? The classmate said, “Actually, he should have been put on it a long time ago.”

Wu Yan, a doctor at Wuhan Central Hospital, told People late last night that after Li Wenliang was transferred to the other campus yesterday afternoon, his condition was very poor: “He wasn’t suitable for transfer; the risk was high. He was transferred over in the evening, and not long after he arrived he went into respiratory failure and was intubated, but we couldn’t bring him back. His breathing and heartbeat stopped. After three hours of chest compressions there were no vital signs, but we still put him on ECMO. Right now we’re not allowed to declare him dead.”

“Even though I know he’s probably already gone, I still hope the rumors online are true—that ECMO can create a miracle,” the doctor told People at 00:43 this morning.

“What I learned tells me it’s basically impossible, but I still feel there might be a miracle,” the doctor explained from his medical knowledge. “Breathing and heartbeat stopped for three hours—normally you can declare clinical death. But we got an ECMO machine to maintain circulation.”

According to Caixin, at 2 a.m., the resuscitation was still ongoing. At 3:48 a.m., the official Wuhan Central Hospital account posted: Our hospital’s ophthalmologist Li Wenliang, unfortunately infected while working to combat the novel coronavirus epidemic, despite all-out rescue efforts, passed away at 2:58 a.m. on February 7, 2020. Three hours of chest compressions, at least three hours of ECMO—no miracle was created.

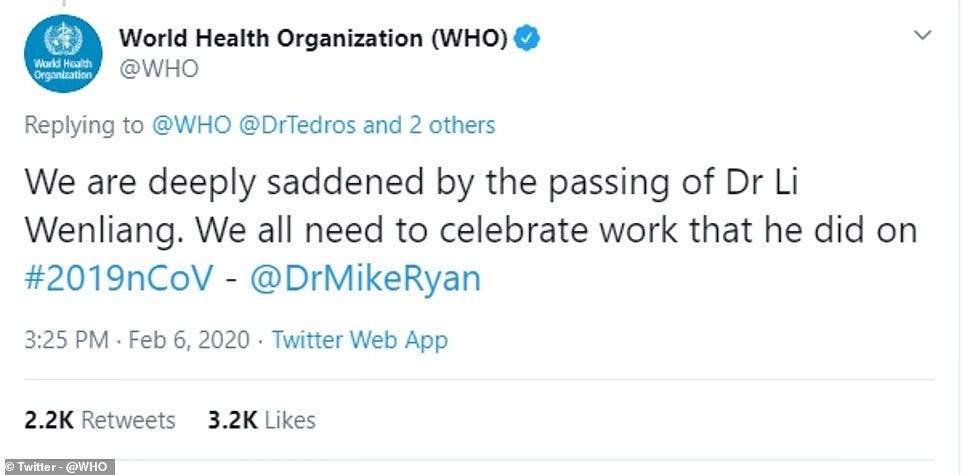

Before that, at 23:25 last night, the World Health Organization had already posted a tweet: “We are deeply saddened by the passing of Dr. Li Wenliang. We all need to celebrate work that he did on #2019nCoV.”

2

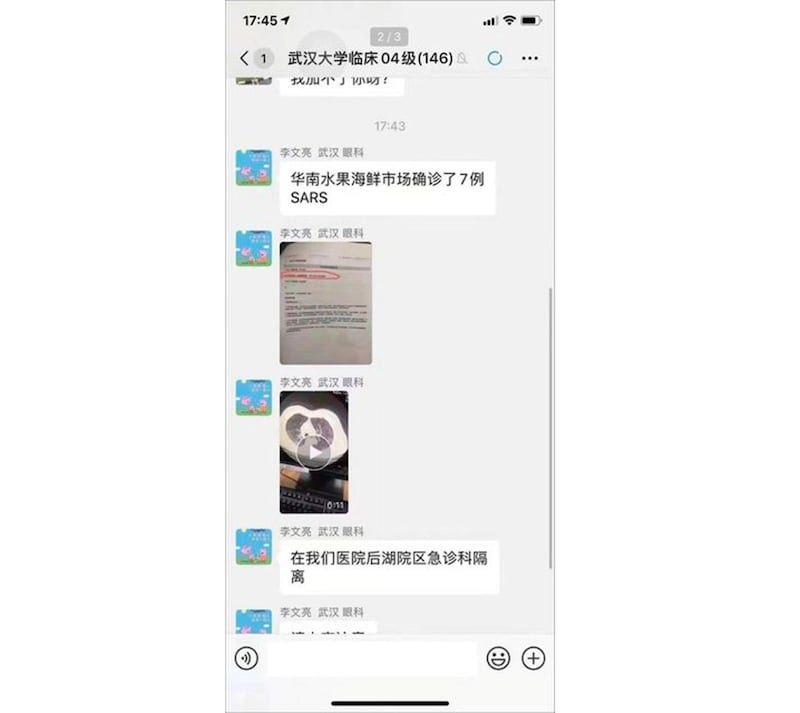

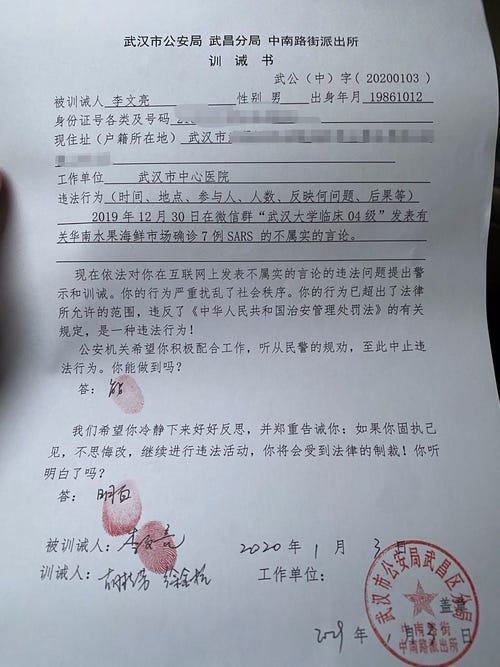

Li Wenliang’s university classmates told People that on the afternoon of December 30, 2019, Li Wenliang posted in their class group chat: “华南水果海鲜市场确诊了7例SARS,在我们医院后湖院区急诊科隔离。Seven confirmed SARS cases at Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market; isolated in the ER at our hospital’s Houhu campus.” Half an hour later, he added: “最新消息是,冠状病毒感染确定了,正在进行病毒分型。让家人亲人注意防范。Latest news is that coronavirus infection has been confirmed; virus typing is underway. Tell family and loved ones to take precautions.”

As fellow doctors, they believed Li Wenliang. He had practiced for many years; his judgment was unlikely to be wrong. And precisely because of Li Wenliang’s warning, they began protecting themselves from that point on—stockpiling N95 masks and wearing protective suits at work. Not many people knew at the time, so masks were still easy to buy. It was exactly this batch of supplies that protected some doctors at the beginning of the outbreak, and later, when supplies were scarce, helped them through urgent moments.

After Li Wenliang was reprimanded, his classmates all learned about it. They became even more cautious and stopped talking about the new virus on WeChat, but they still spread the information by word of mouth—especially many young doctors born in the 1980s, who, after learning about it, began taking precautions. A classmate said, “So he really saved a lot of people.”

(China Central Television news reporting on Wuhan police reprimanding eight people “spreading rumors” on unknown pneumonia, including Dr. Li Wenliang.)

Before he was reprimanded, Li Wenliang was not a well-known doctor in the hospital. Wu Yan, a young doctor in another department, hadn’t really heard his name and had never met him. “I only learned about him because he was called a rumor-monger. He was reprimanded, and we all felt it was unfair to him. Then we heard he got infected… He was being punished on one side and got infected on the other, and his family got sick too. I heard the psychological pressure was huge. Later he was rehabilitated, and we were all very happy.”

From the bottom of his heart, he admired Li Wenliang’s courage: “All I know is, he told the truth—he said what many people didn’t dare to say. But he received a punishment that didn’t match it at all, and suffered enormous trauma, physically and mentally.”

That night, Wu Yan’s WeChat Moments feed was “flooded with candles.” Although, when he was being interviewed by People, Li Wenliang had not yet been officially declared dead, his heart had already been stopped for three hours. Wu Yan said, “We all know that mourning Dr. Li is also mourning ourselves.”

At 1 a.m., Li Wenliang’s university classmates were still weaving through the inpatient building, which had been locked down everywhere, searching for any passage that might still be open. They wanted to reach the floor where Li Wenliang’s parents were hospitalized—at least to get a look at them and know whether they were okay. But after trying for two hours, they still didn’t succeed.

As they searched for an exit, they passed wall after wall displaying the glorious history of Wuhan Central Hospital. Another wall bore the hospital motto: The hospital takes saving lives and healing the wounded as its sacred duty. Harm, pain, and withering of life play out every day; the most valuable lesson they bring is awe and cherishing. To revere life is to treat patients like family, to care for patients’ life and health, to put people first, and to treat employees with sincerity.

3

Dr. Li Wenliang’s Weibo posts recorded his vivid yet ordinary everyday life.

He loved food and often joked that his “appetite is fiercer than a tiger.” If he suddenly wanted to eat oranges, he would run 1,000 meters in a storm wearing slippers just to buy them. Seeing all kinds of ice cream in an ice cream shop, he would sigh, “Damn, too many temptations.” Izakayas and Haidilao were both his favorites; he said he absolutely loved wasabi and sashimi. Fried chicken was another favorite. Dicos’s “pistol drumstick”—every time he went to the train station, he would order it. He described how delicious that drumstick was: a huge leg connected to the hip, just looking at it was deeply satisfying; the skin crisp, the meat tender, paired with the restaurant’s special dry spice mix—absolutely a top-tier leg among legs! Add a cup of Coke at this moment, and life has already reached its peak.

He binge-watched dramas—he liked Joy of Life—and he followed idols too. Recently he liked Xiao Zhan, thought Xiao Zhan was handsome, and felt he sang 《绿光》Green Light especially well. When cherries cost 158 yuan per 500 grams, he would joke that he couldn’t afford them. Buying a few oranges for 30 yuan, he would call himself a “diaosi”—a loser—and sigh that life was hard. He also loved reposting giveaway posts on Weibo: repost to win a phone, repost to win a car, repost to win cherries—he reposted them all. Finally, once, he stopped being someone who never wins: he won a box of wet wipes, and he posted on Weibo to thank the sponsor.

Being a doctor was exhausting, and from time to time he would complain about work: “This is killing me.” Although he often said “I don’t want to do this anymore,” complained about being on duty three days in a row—“I’m going to die”—said he “hated outpatient clinic,” and looked forward to getting off work to go eat crispy sweet & sour pork, if you really asked him to leave, he couldn’t bear to take off the white coat. What he truly felt inside was: “Patients torment me a thousand times, yet I treat patients like my first love.”

Reading his Weibo, you’d find him kind of adorable. This ophthalmologist seemed to have a little boy living in his heart, joking and raging on social media, with “damn it,” “what the hell,” and “holy crap” constantly on his lips. He would even wonder, “Does a chicken suffer when it lays an egg?” If he saw a butterfly, he’d take a photo and post it online with the caption: A butterfly. When he had time, he liked going out for a walk, looking at rapeseed flowers, playing badminton. If someone on the road called him “uncle,” he would “go crazy,” feeling “hurt.” He also loved pranks: when checking out of a hotel, he would fold the blanket into the shape of a person inside to scare the housekeeping staff.

If you asked what season he liked best, it would probably be autumn. He liked autumn mornings, when sunlight filters through green leaves and scatters specks of light on the ground. He once described Wuhan in autumn like this: it has a kind of gentle warmth that is neither hot nor cold; in this season you can feel the most pattering drizzle and the softest wind, and of course you can feel the beauty and the fluttering of fallen leaves covering the ground, and the heart-stirring sound of them crunching underfoot.

Dr. Li Wenliang shared warm moments of being with his family: the weather was nice, his child and wife were by his side, his parents came to visit him, and when they left on the high-speed train, he would specially take a photo of the train they were riding to commemorate it.

He once made a New Year’s wish: in the new year of his life, he hoped to be a simple person—able to see through the complexities of the world without leaving traces in his heart, and to keep a calm and ordinary mind. He also said that an unexamined life is not worth living, and he hoped everyone could realize their own value—encouraging each other. His WeChat signature was: “理论是灰色的,生命之树常青 Theory is gray, but the tree of life is evergreen.”

But at the same time, he was someone who cared about society. He spoke up for the outspoken host Wang Qinglei after the Wenzhou high-speed train accident, calling for signatures to reinstate him. On February 1, he gave an interview to Caixin. Even though he had already been reprimanded and both he and his parents had been infected, he still bravely expressed himself: “A healthy society shouldn’t have only one voice.”

That same day, his nucleic acid test result came back—positive. He said: “Dust settles; finally diagnosed,” and added a dog emoji. In the hospital ward, he saw many netizens’ encouragement and thanked everyone on Weibo: “Thank you all for your support. My license hasn’t been revoked, so please rest assured. I will definitely cooperate actively with treatment and strive to be discharged as soon as possible.”

Before that, when a work group chat called on doctors to sign up for the front line of epidemic prevention, he also said: “When I’m better, I’ll sign up too.” In another image circulating online, someone asked him on WeChat: After you recover, what are your plans? He replied: When I’m better, I’ll go to the front line. The outbreak is still spreading—I don’t want to be a deserter. (Enditem)

Thanks for this. I was in Wuhan when it went down, locked up for months, scared... Dr. Li's story resonated then and even more now. One voice.

Impressive personality.