Li Xunlei warns of illusion of warmth in the economy

Japan’s lost decades show why household spending, not infrastructure, is the cure for a long freeze, said Zhongtai Chief Economist.

Japan’s long stagnation has long served as a cautionary tale for policymakers across Asia. After the collapse of its asset bubble in the early 1990s, hesitant monetary easing, zig-zagging fiscal choices, a banking clean-up that came late, credit drifting into property, and a failure to nurture new industries did little to revive household demand or lift productivity. Li Xunlei, Chief Economist at Zhongtai Financial International Limited, revisits this history in a new essay that is ostensibly about Japan, but whose warnings are clearly aimed closer to home.

As he did in a recent piece featured in The East is Read, Li aims to counsel Beijing to avoid Japan’s missteps: curb the urge to splurge on concrete, especially in areas losing people. Instead, he contends, raising household incomes and encouraging consumption are far more promising ways to prevent China’s own economy from slipping into a prolonged chill.

The article remains available on Li’s personal WeChat blog.

—Yuxuan Jia

失温时为何会感受到“热”

Why Does Hypothermia Sometimes Feel Like “Heat”?

I have read many accounts of hypothermia, the most striking being that of Lincoln Hall, the Australian mountaineer who, in 2006, fell ill during his descent from Everest. Believed dead and left above 8,000 metres in −30°C conditions with severe hypoxia, he survived the night. When rescuers reached him, they found him trying to remove his jacket.

Another widely reported case occurred in May 2021, during the 100-kilometre ultramarathon at the Yellow River Stone Forest in Baiyin, Gansu province. Extreme weather struck the course, and 21 participants lost their lives to hypothermia.

Clinically, hypothermia refers to a condition in which the body loses heat faster than it can generate, leading to a fall in core temperature (below 35°C). This triggers a series of symptoms, including shivering, confusion, cardiovascular and respiratory failure, and, in severe cases, death.

A study by Swedish medical researchers examining 207 fatal cases of hypothermia found that in 63 instances the victims exhibited what is known as “paradoxical undressing.” Why does this happen? When core temperature drops too low, the brain’s ability to sense and regulate temperature deteriorates. Peripheral blood vessels dilate abnormally, causing blood to rush to the skin’s surface and creating a false sensation of warmth. At the same time, disrupted neural signalling can trick the individual into believing they are overheating.

I am not a medical specialist, but I wonder: when an economy “cools into hypothermia,” can markets also experience an illusion of warmth? And how destabilising might such false signals be for the economy?

Why does perceived temperature differ so greatly from the actual reading?

There is often a marked gap between how people feel about the economy and what the data show. Economic indicators are frequently lagging, as they record events that have already occurred. Perspective on the macroeconomy is inevitably limited—like the proverbial blind men feeling an elephant. Moreover, humans are emotional by nature and tend to place disproportionate weight on present conditions. The result is frequent misjudgment.

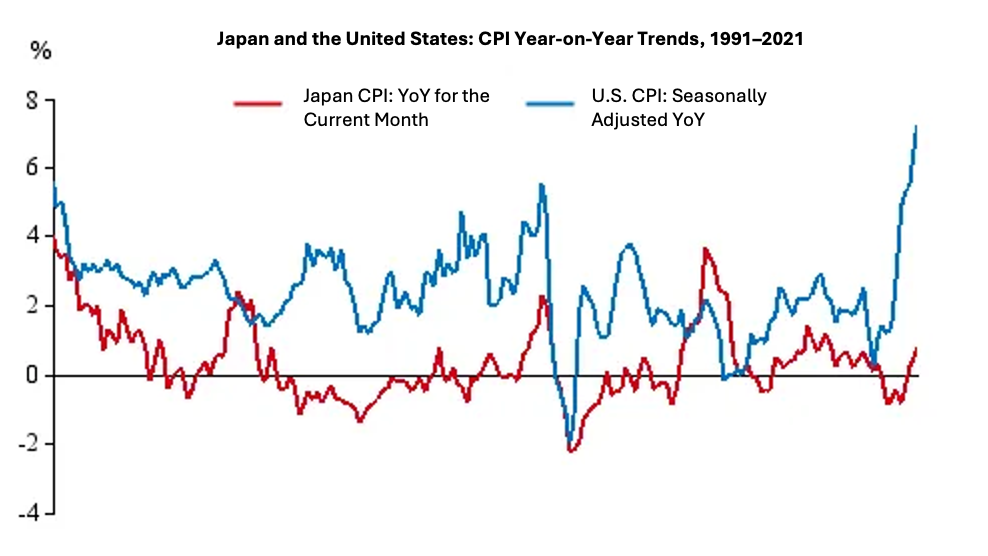

The first example that comes to mind is Japan’s “lost three decades.” After the collapse of its property bubble in the early 1990s, Japan slipped into long-term deflation. In 1991, the year real estate prices peaked, the consumer price index (CPI) stood at 93.1. By the end of 2021, it had risen only to 100.1, a cumulative increase of just 7.5% over three decades, averaging a mere 0.25% per year. Although the CPI saw brief upticks during episodes such as the Asian financial crisis and the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis, over the 30 years since the bubble burst, it has consistently hovered around zero.

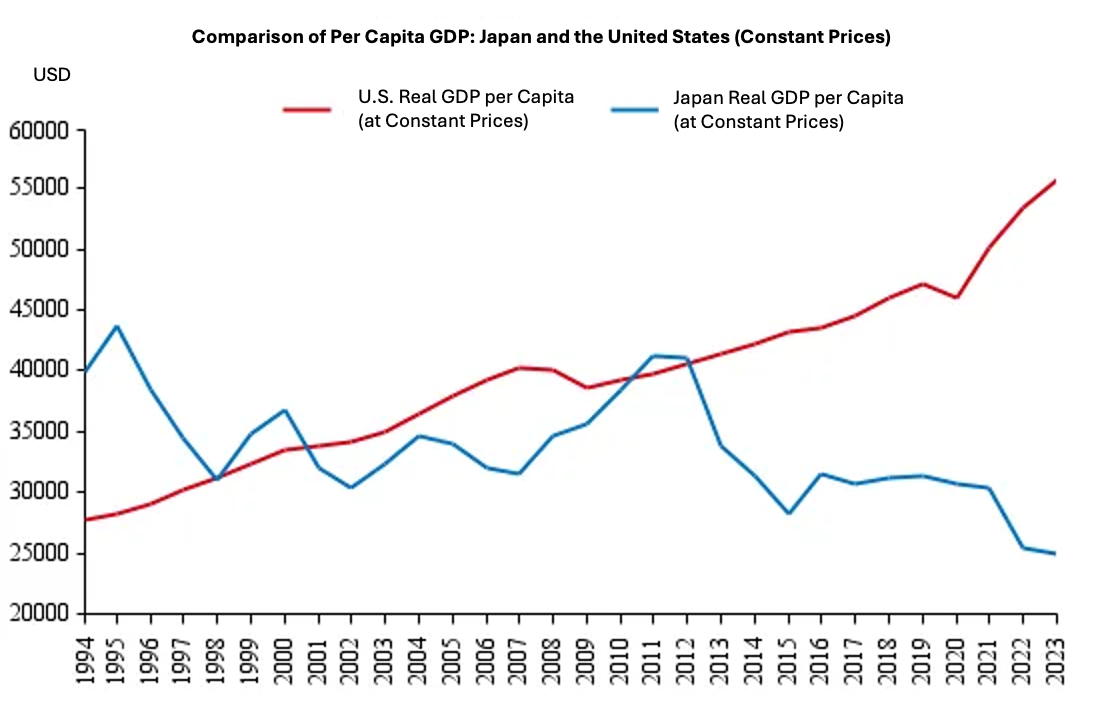

If Japan’s deflation is understood as a form of “hypothermia,” then the Japanese economy remained in that condition for three decades—the so-called “lost three decades.” Measured in U.S. dollars, Japan’s per capita GDP in 1991 was USD 28,666 (calculated at the year’s average exchange rate). By 1994, it had risen rapidly to USD 38,467. In other words, within three years of the property bubble’s burst, per capita GDP increased sharply. The main reason was the swift appreciation of the yen: from JPY 145 per dollar in 1990 to JPY 94 per dollar in 1995.

In 1994, Japan’s per capita GDP ranked first in the world, even though the country was already grappling with rising levels of non-performing loans, the collapse of certain banks and securities firms, sharp declines in corporate profits, and a severely weakened economy. Thirty years on, by 2024, Japan’s per capita GDP stood at only USD 32,420. Adjusted to constant 1994 prices, that figure amounts to roughly USD 25,824, around 33% lower than it was three decades earlier.

By contrast, U.S. per capita GDP in 1994 was USD 28,000. Adjusted to constant 1994 prices, per capita GDP reached USD 57,000 by 2024, more than double the level three decades earlier.

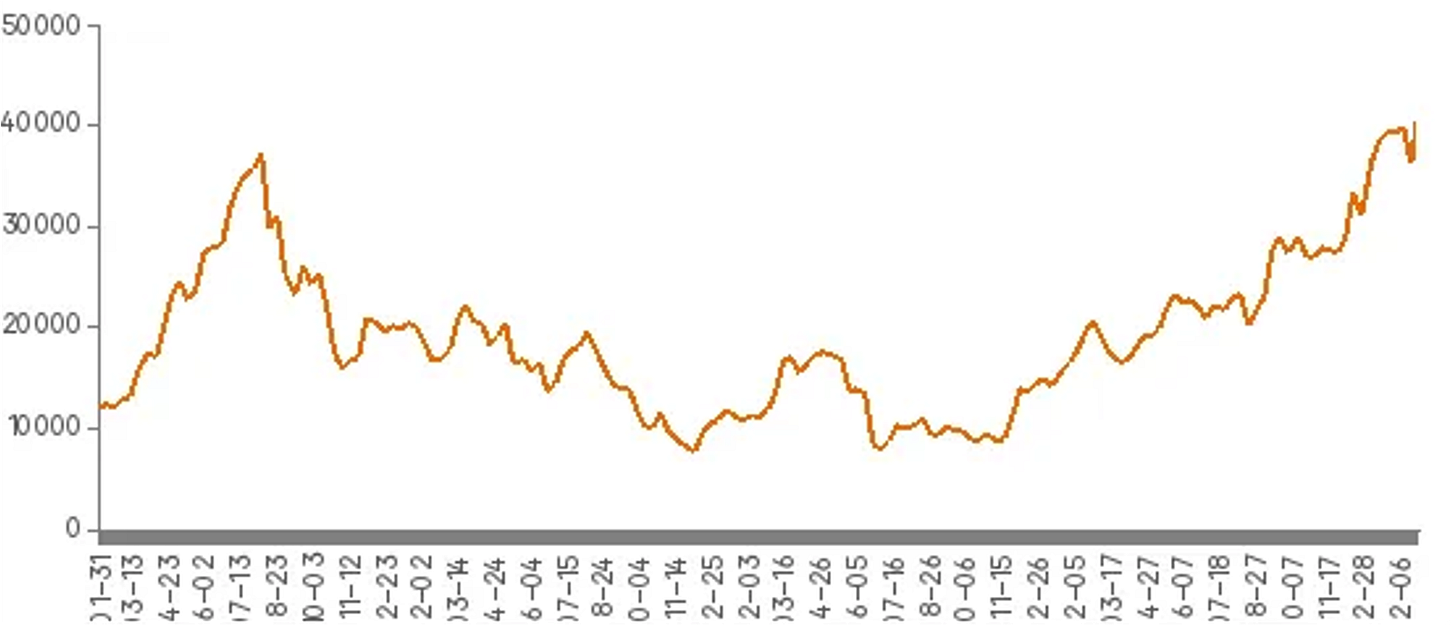

From this perspective, Japan has not only endured a “lost three decades” but, in terms of per capita GDP, may even have regressed relative to thirty years ago. The stock market, often regarded as a barometer of the economy, tells a similar story. At the end of 1989, the Nikkei 225 peaked at 38,900 points. It then entered a steep decline. Despite multiple rebounds along the way, by July 2012 it stood at just over 8,700 points, a mere fraction of its 1989 level.

Japan’s economy clearly went through a prolonged period of “hypothermia.” What is puzzling, though, is why, over such a long span, the authorities failed to take effective measures to restore the economy to “normal temperature.”

This was closely related to a series of misjudgments by the Japanese government at the time. For example, policymakers underestimated the impact that the collapse of the real estate bubble would have on the economy. The Economic White Papers released by the Economic Planning Agency of Japan in 1991 and 1992 suggested that the negative effects of the bubble’s collapse on household consumption and corporate investment were very limited and would disappear after 1993.

At the same time, the Japanese authorities failed to pay sufficient attention to the risks facing financial institutions. During the 1990s, a wave of bank failures occurred, including the Daiwa Bank, Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, and the Long-Term Credit Bank of Japan. The major securities trading firm Yamaichi Securities also collapsed. These failures were closely tied to the large number of corporate bankruptcies during the same period.

On the macroeconomic policy front, monetary policy did not shift from tightening to easing in a timely manner. The Bank of Japan hesitated over rate cuts: beginning in August 1990, it kept the official base rate at 6%. Only in July 1991—eighteen months after the stock market had already fallen—did the central bank begin cutting rates, ultimately lowering them to 0.5% by September 1995. This slow response was one reason Japan failed to escape deflation quickly.

Fiscal policy also lacked consistency, as the Japanese government oscillated between expanding spending and pursuing fiscal consolidation through tax increases. For example, in 1997 the consumption tax rate was raised from 3% to 5%, some tax reduction measures were withdrawn, and households’ share of medical costs was increased. The lack of coordination between fiscal and monetary policies was related to frequent leadership changes. Between 1991 and 1998, Japan had seven prime ministers, each with a different approach to addressing the economic malaise.

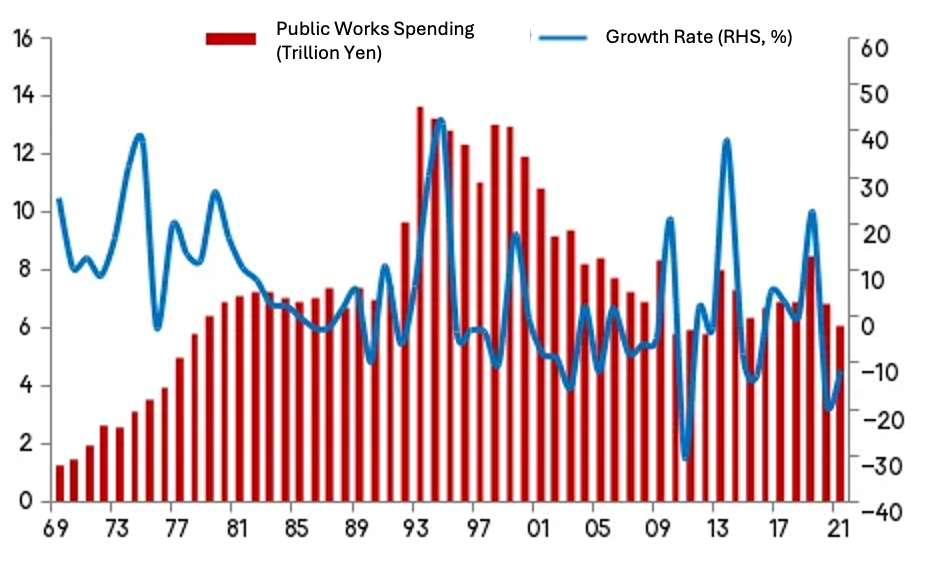

It is not difficult to see that Japan’s fiscal policy at the time was poorly targeted, with actual fiscal spending in the early years too limited and efficiency relatively low. During expansionary phases, the government remained fixated on production-oriented investment, channelling large amounts of public funds into infrastructure projects in remote regions. These measures failed to stimulate private consumption and investment, and produced little in the way of a meaningful multiplier effect.

The chart above shows that between 1992 and 1996, Japan’s public works spending rose sharply. Yet much of the infrastructure investment flowed into roads, bridges, tunnels, large dams, and flood-control projects in regions with rapidly declining populations, yielding poor returns on investment. Local governments also built lavish civic halls, museums, and stadiums. These projects drove up government debt, while many of the facilities remained underused. Meanwhile, young people continued to migrate to metropolitan centres such as Tokyo.

Why did such ineffective investments occur? One reason was political: the Liberal Democratic Party, which had been in power for decades, drew much of its electoral base from remote areas. Another was the traditional belief in balanced regional development, the assumption that new transport links could help close the wealth gap. In early 1996, the newly established Hashimoto Cabinet, confronted with ballooning fiscal deficits and rising public debt, introduced “Six Areas of Reforms” (Muttsu No Kaikaku), which in practice amounted to a programme of fiscal contraction.

What lessons does prolonged “hypothermia” offer?

In 2002, an American writer named Alex Kerr published a book titled Dogs and Demons. The seemingly odd title, in fact, draws on a well-known Chinese idiom: “It is easiest to paint demons,” which Kerr used to allude to Japan’s predicament: there is no panacea for deep-seated problems, but it is all too easy to spend lavishly on showcase projects. Between 1995 and 2007, Japan’s infrastructure budgets totalled about JPY 650 trillion, three to five times the U.S. level over the same period. The Chinese edition of the book was also endorsed by the economist Wu Jinglian.

I often say that on the way up a mountain there are downhill stretches, and on the way down there are uphill stretches, but neither alters the overall direction of travel. In financial markets, a technical bull market is defined as a rise of more than 20% from a clear low; such an increase does not necessarily indicate an improvement in fundamentals. So, if an index climbs by more than 50%, does that constitute a genuine, economy-reflecting bull market?

During its long decline, Japan’s stock market saw three sizeable “bull runs.” First, in June 1995, Japanese banks put up roughly JPY 2 trillion in a financial stabilisation fund, and in September the Bank of Japan (BOJ) cut its policy rate from 1% to 0.5%, ushering in the zero-interest-rate era and extremely loose monetary policy. From June 1995 to June 1996, the Nikkei 225 rose by 55%.

Second, in 1998, amid the Asian financial crisis, the yen depreciated sharply, and banks came under severe strain. The Japanese government injected capital into the banking system, the BOJ intervened heavily to purchase yen, and JPY30 trillion was earmarked for public investment. From September 1998 to March 2000, the Nikkei 225 rose by 52%.

Third, from April 2003 to July 2007, the Nikkei 225 rose from a little over 7,800 to 16,800, an increase of 132%. This phase coincided with a global upswing led by emerging markets. Over the same period, U.S. equities experienced a major bull market, and China’s A-shares surged even more sharply, with the Shanghai Composite climbing from 1,000 to above 6,000.

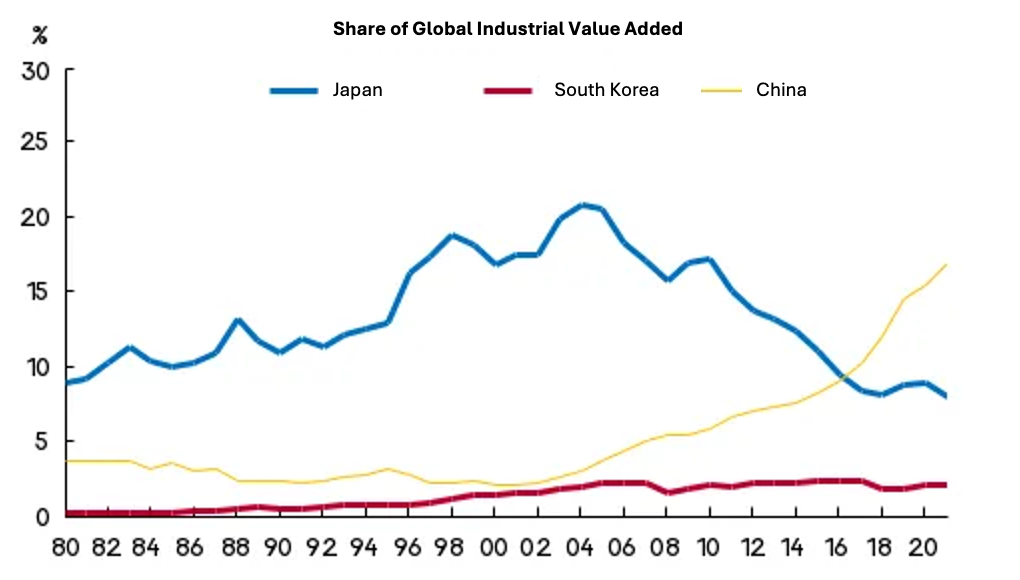

What deserves deep reflection, however, is why the Nikkei 225 ultimately fell back toward historical lows. The reason is that, after the real estate bubble burst in 1991, Japan failed to cultivate new industries with a global impact. Whether e-commerce in the internet era, smartphones, new energy, electric vehicles, drones, new-generation robotics, or today’s fiercely contested artificial intelligence, Japan did not fully commit to participation. Without the rise of new sectors, legacy industries inevitably become sunset industries; in the absence of industries or firms with compelling profit-growing prospects, market confidence and expectations naturally falter.

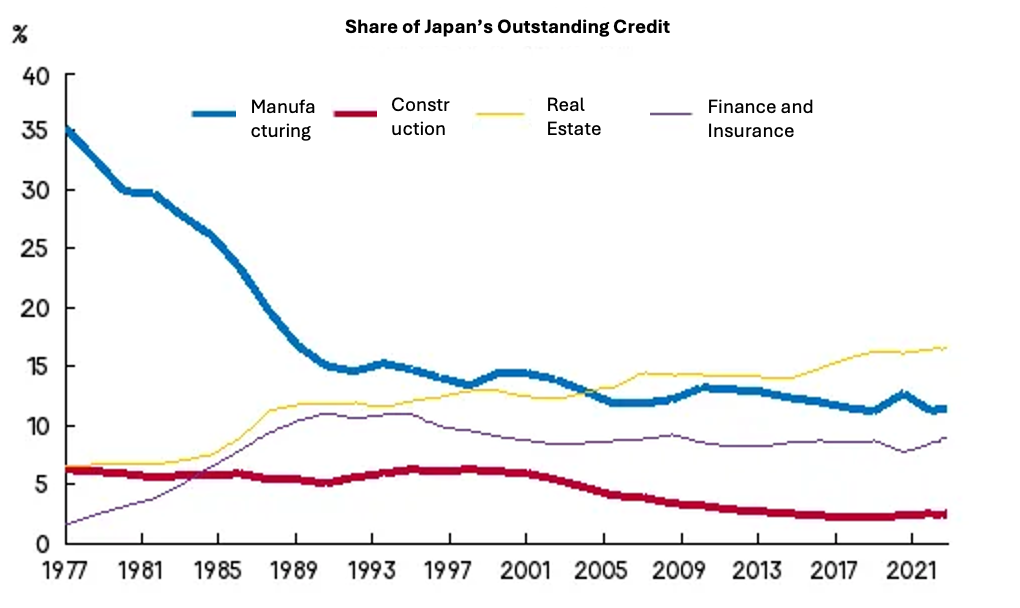

From the perspective of Japan’s credit allocation, investment in the manufacturing sector has continued to decline, while real estate lending has maintained an upward trend. This reflects the hollowing out of manufacturing: its share of outstanding credit fell from 35% in 1977 to 11% in 2021. By contrast, the share of real estate loans rose from 12.4% in the aftermath of the 1993 bubble collapse to 16.7% in 2021.

Fluctuations in shares of outstanding credit: Japan’s manufacturing vs. real estate

Why did the share of outstanding credit to manufacturing in Japan continue to decline? This was likely tied both to the sharp appreciation of the yen in the early 1990s and to China’s reform and opening. Currency appreciation tends to encourage overseas expansion, while depreciation supports exports. In the first half of the 1990s, the yen appreciated dramatically while the renminbi depreciated significantly. Japanese firms responded by shifting large-scale investment abroad, particularly into China. The resulting inflow of global capital contributed to a sharp rise in China’s share of global industrial value added, while Japan’s share moved in the opposite direction.

In 1992, Japan’s government debt balance stood at just 69% of GDP. By 2021, the ratio had soared to around 225%. Yet this steep rise in debt failed to generate a corresponding economic recovery, underscoring a very weak multiplier effect. Japan’s experience, therefore, warrants careful reflection: investment can indeed serve as a tool to stabilise growth, but the critical question is, investment in what?

First, excessive spending on infrastructure with diminishing marginal returns is misguided and hugely wasteful, as in the case of motorways with insufficient traffic. Second, directing too much investment to remote areas, running counter to population flows, yields extremely weak multipliers. Third, what is truly needed is forward-looking industrial policy: capital investment by the government to upgrade manufacturing is essential if a country is to maintain global competitiveness.

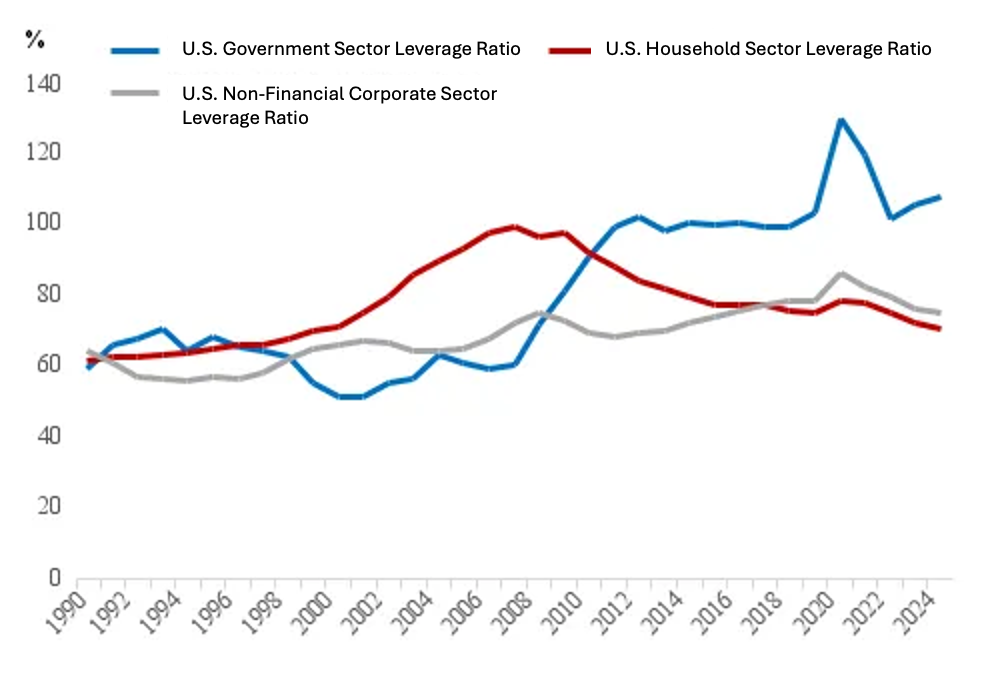

Then, is it possible to reduce government leverage? Almost certainly not. In a real estate downturn, both households and corporations deleverage; the economy can only look to the government to leverage in order to sustain equilibrium. Japan’s missteps lay in policy oscillations: at times believing the economy was overheating, at other times seeking to rein in deficits by raising the consumption tax in the face of mounting government debt and falling fiscal revenues, thereby shifting fiscal policy from expansion to austerity.

For example, the Hashimoto administration, which took office in early 1996, introduced the “Six Areas of Reforms” to address large fiscal deficits and public debt burdens. In practice, these measures amounted to fiscal contraction. In 1997, the consumption tax rate was raised from 3% to 5%, certain tax breaks were withdrawn, and the share of medical costs borne by households was increased.

Across advanced economies, a clear pattern emerges: once societies enter deep ageing (an elderly population share above 14%), government debt ratios rise and economic growth slows. Therefore, temporary deleveraging may occur, but the long-term trend is upward. The crucial question is how public spending is deployed. Japan channelled most resources into infrastructure; the United States, by contrast, prioritised boosting household incomes and consumption. The American approach has proved far more effective.

Macroeconomics is a vast system and requires systemic thinking. Investment can stabilise growth; so can expanding consumption. But if public investment is increased blindly, it risks creating structural imbalances and oversupply. In Japan’s stimulus packages of the 1990s, support for consumption was insufficient—a key reason for prolonged deflation. Even after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe set a 2% inflation target in 2012, Japan never fully escaped deflation, because wage growth remained sluggish. The lesson is clear: to take a leaf out of someone else’s book.

Unfortunately, this misreads both Japan's experience and the dynamics of economic growth and development generally.

The lost decades emerged as a result of the capitulation to geopolitical pressure from the US, which saw the Yen re-valued up (dampening Japanese industrial competitiveness), which then saw system liquidity channeled into domestic real estate. Excessive real estate-backed leverage has left its mark. Industrial stagnation also took place due to the effects of US pressure. Contrary to the “stagnation” trope, Japanese households retained a high quality of life: excellent public infrastructure, universal healthcare, stable employment until the 1990s reforms, and relatively equal income distribution. Japan’s per capita consumption and welfare levels were never in crisis in the way implied by “lost decades.”

The real story is not about failed investment or household retrenchment, but about how external geopolitical pressures and internal financialisation reshaped the circuits of accumulation. Japan’s “lost decades” were thus less an economic failure than a political-economic realignment: from industrial dynamism to asset-driven financialisation.

The trope advanced here also doesn't explain where household spending come from in the first place? Li's commentary simply doesn't realise that households only get to spend what they earn; and what they earn comes from exogenous sources ie., independent of income. In other words, it is investment that drives household income growth.