Liu Daoyu, "Eternal President of Wuhan University," dies at 92

A widely respected educator who believed "control and planning will never reinvigorate education" is remembered.

Today, China’s universities are often held up as a triumph. Chinese-trained talent fills America’s AI labs, and the country now tops the Nature Index of leading scientific journals. To many observers, the conclusion writes itself: China has built a world-class university system.

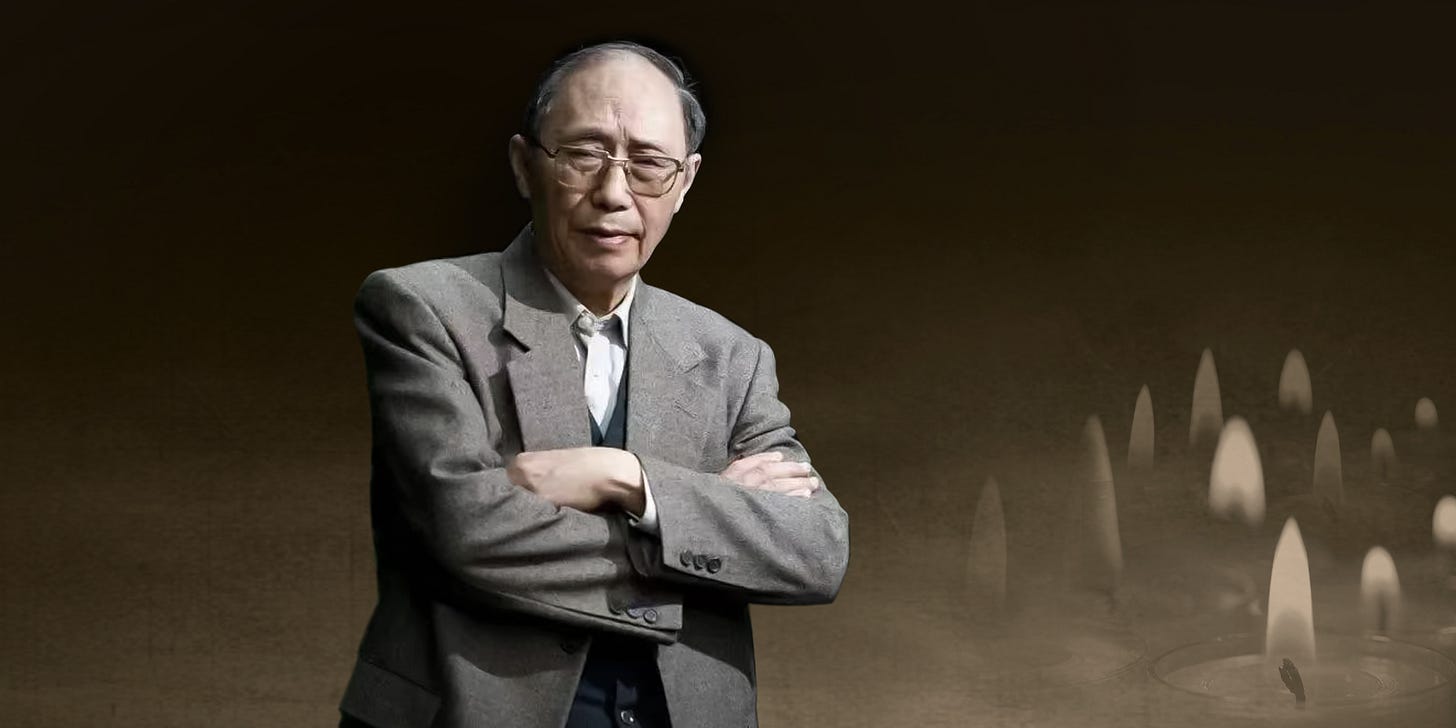

Success—or the appearance of it—has smothered debate. For more than two decades, the sharpest critiques of China’s universities have gone largely unanswered. The loudest, and most singular, belonged to Liu Daoyu, the former president of Wuhan University, who died on November 7, 2025. He is mourned as the school’s “eternal president”—a phrase that says less about nostalgia than about the present. The implication is pointed: Chinese universities are run as bureaucratic outposts rather than communities of scholarship.

Liu was no outsider. Born in 1933, he was a decorated member of the Communist Party of China who helped organise the landmark 1977 symposium chaired by Deng Xiaoping that restored the national college entrance examination and reopened intellectual life after the Cultural Revolution. That decision reshaped the fate of millions and remains one of the most consequential events in modern Chinese education. It was also the beginning of Liu’s long public devotion to education as a national calling, not a bureaucratic chore.

He became most closely associated with Wuhan University’s “golden years” in the 1980s. He pushed through a series of reforms that were then unheard of on the Chinese mainland: a credit system, double-major programmes, minor systems, flexible transfers between departments, and admissions for students from other universities. They landed like stones in still water, sending ripples across a higher-education system that was rigid, hierarchical, and allergic to experimentation. Liu placed the development of students’ individual potential—rather than ideological conformity—at the centre of the university’s mission. Wuhan University briefly became an academic oasis: open, restless, inventive. In a decade when China longed for modernity, Liu offered not just administration but imagination.

One anecdote from his tenure still circulates. During a grassroots election for the National People’s Congress, a law student announced he would run—against a list of approved candidates. Some laughed; others braced for trouble. Liu quietly supported him. The student won with more than 7,000 votes. It was a tiny glimpse of civic possibility inside a university campus. Such moments have not been seen for a long time.

In a 2012 interview with Southern Weekly, Liu was asked which achievement he valued most. He replied:

“Creating a democratic, open campus culture. Freedom is the soul of education. Students could skip class, choose majors, skip grades, grow long hair, dance, and fall in love. Many universities cut electricity at 10 p.m.—why? Students are adults. Some sleep early, some late. Turning off the lights just forces night owls to lie awake. Students should decide for themselves.”

His reforms were bold, sometimes naïve, and always disruptive. They also cost him. His abrupt firing in 1988 was widely interpreted as the price paid by an idealist in a system that tolerates order more easily than dissent. Yet his exit was not the end but a transformation. Freed from administration, he became a public critic and an independent thinker—writing, lecturing, attacking the bureaucratisation of education with the plain, stubborn voice of someone with nothing left to lose.

He spent the remainder of his life as a moral irritant—a reminder that a university is not a ministry, a campus is not a garrison, and education is not the manufacture of obedient functionaries. He offered students possibility, not moulds; questions, not dogma. He believed that a university’s authority must rest on scholarship, integrity, and reform—not on rank or government pedigree. In a system where “education officials” almost always overshadow “educators,” that distinction made him rare.

In a 2015 interview with 人物 magazine, he grew emotional - ““I wish I could help, but I can’t” - when speaking of China’s educational drift:

“Write what you can; omit what you cannot. You cannot lose your job. I have nothing to lose… As Qian Mu said: recognize only truth, not personal gain; even on the chopping block, hold to truth. That temperament has made my life a difficult one— it is simply how I am made.”

This is why his passing feels larger than the death of an individual. Liu Daoyu belonged to a generation of educational idealists—men and women who believed that a university should liberate the mind, not patrol it; cultivate character, not just credentials. China has world-class students. Liu Daoyu spent his life asking whether the country would build world-class universities for them. His voice is now silent. His question is not—even if those students are already changing the world.

Below is an article in 中国高校之殇 The Woes of China’s Higher Education, a 2010 book by Liu.

Independence and Autonomy: The Only Direction of Education System Reform

What is the responsibility of leaders? Mao Zedong once said: “The responsibility of leadership, summed up, mainly consists of two things: offering ideas and using cadres…” What he meant was that leadership must grasp major matters, focusing on macro-level decision-making. Modern theories of leadership science also point out: “Whatever can be delegated to others, do not do it yourself.” These views accord with China’s ancient concept of “governing by doing nothing (wuwei),” and are also basic principles of effective contemporary management, allowing the greatest possible mobilization of people’s initiative and creativity.

However, our current educational leadership system is not like this. They control all educational resources and monopolize all decision-making and administrative power. This clearly contradicts modern management principles and the operational mechanisms of a market system. Why do national and local educational authorities insist on doing everything themselves? Why not focus on reforming the educational system and delegate power to independent school-runners? Why, after 20 years of reform and opening up, is the Ministry of Education still stuck at the level of the planned economy?

In terms of ideological roots, the influence of planned-economy thinking is profound. Now, people over the age of 40 mostly graduated from schools under the old educational system. Whether the specialized training they received or the ideological indoctrination they experienced, it was all the logic of the planned economy. Without innovative values and a fearless reforming spirit—if one looks at everything as normal and unremarkable, and merely adapts rather than seeks change—then nothing will be transformed. Especially after some of these people enter leadership positions, they prefer to maintain the status quo rather than take risks for reform. This is why reforms tend to arise spontaneously from the grassroots, while top-down reform initiatives are few.

The “education exceptionalism” has obstructed educational reform. For a long time, education has been regarded as part of the superstructure and deeply affected by ideology. Although the era of treating education as a “barometer of class struggle” and a “tool of proletarian dictatorship” is gone, the idea that education’s purpose is to train revolutionary successors of the proletariat is still widespread. Therefore, there remains deep wariness toward private schools, church-run schools, schools run by non-governmentla forces, university independence, professor governance, student self-government, academic freedom, and so on—always fearing the loss of the proletariat’s leadership over the school system.

“Official-centrism” is another obstacle to decentralization. Historically, this mentality has deep ideological roots, traceable to Confucius’ two-thousand-year-old idea that “the best scholars should become officials.” The famous Taiwanese scholar Ch’ien/Qian Mu once said: “There is no Chinese intellectual who is not happy to enter politics; being an official is their religion.” This is not an exaggeration. Today, the trend of scholars becoming officials is flourishing, to the point that some media have called for: “Stop the trend of star professors becoming officials!”

Oddly, almost all Chinese officials studied natural sciences or engineering; among them are academicians, famous scholars, doctoral supervisors, professors—yet those who studied political science, economics, law, or management rarely become high-ranking officials. This is indeed a strange phenomenon in Chinese officialdom. Ultimately, “being an official” symbolizes identity, power, status, dignity, and interest. In the past, there was a saying: “Power expires if left unused.” So once someone becomes an official, no one will easily give up power; they must use it fully and enjoy their authority. I dare not say all officials are like this, but there are certainly many with such a mentality, and it is precisely these people who obstruct educational reform. People often complain that education has too many “nannies.” In addition to educational leadership departments at all levels, there are also inexplicable systems of supervisors and inspectors—for example, appointing a retired former Party secretary who knows nothing about education to serve as a regional inspector. This is yet another manifestation of official-centrism.

The rigid educational system has already become a major difficulty for China’s education reform, and will eventually become a bottleneck restricting economic development. I believe the central government should convene a special national education work conference, using a method combining experts and the masses—especially relying on reform-minded educational practitioners—to enrich and revise the 1985 “Decision on Education System Reform,” and reissue an authoritative document on education system reform as the basis for carrying out reform.

At present, at least the following reforms can be implemented:

First, formulate an Education Appropriation Law to legally regulate the distribution of education funding. Everyone must be bound by the law. The law should set multi-factor funding standards based on the nature, tasks, functions, and scale of each school (or province and city), replacing the simple per-student funding method. It should also clearly stipulate the rate of absolute growth in educational spending, rising annually in step with national economic growth, reaching the level of developed countries as soon as possible. Allocating educational funds according to law can eliminate corruption such as personal connections and backdoor dealings, prevent abuse of power, and ensure fairness in education.

Second, educational leadership departments should shift from a controlling function to a service function. The United States is the world’s number-one educational powerhouse; whether in the number of top universities or ordinary universities, it is the largest. Yet historically the U.S. did not have a Department of Education for a long time. Later, a non-cabinet Bureau of Education was established under the Department of the Interior. Not until 1980 was a Department of Education formally created. But the federal constitution grants authority over education to state governments. The federal Department of Education has only two basic functions: (1) build a national education database to provide information for educational evaluation and policy-making; (2) safeguard and ensure fairness in education. This shows that the revitalization of a country’s education does not fundamentally depend on educational administrative organs, but on the initiative of local governments and university educators. Therefore, national educational leadership departments should adopt enlightened policies—grasp more macro decision-making and less micro-management; make more policies and fewer detailed plans; promote more and restrict less; conduct more investigation and research and issue fewer orders; focus more on pilot reforms and hold fewer meetings. If our educational leadership departments could do this, we would certainly mobilize the initiative and creativity of millions of educators across all schools and levels, and would surely open a new era for Chinese education!

Third, universities must have full independence in running their institutions, implementing professor governance. Presidents should be selected by the university’s professor committee, and a genuine system of presidential responsibility should be carried out. “Doing nothing” and “doing something” are complementary: if educational authorities “do nothing,” then university educators can do much. In fact, much of what the Ministry of Education does can be delegated to universities—such as “the project for cultivating high-level creative talent,” and the “implementation plan for national model courses.” There is no need for nationwide uniform plans. Every university’s leaders are insiders and experts; they will naturally handle these matters according to their own conditions and needs. In fact, “national model courses” differ from the old unified national textbooks only in content—the purpose is still uniformity. Furthermore, theories of creative education prove that creative talents cannot be cultivated by any planned project; their development follows individualized and unique patterns. By this logic, the vast majority of the Ministry of Education’s work can be delegated. Do not continue doing thankless tasks that consume much effort with little benefit.

Hmmm. Chinese researchers authored more ultra-high-citation science papers than the rest of the world combined last year: 53% in the top 0.1%.

China had 2,342 papers in that category, the US had 1,511.