Presentation of PKU's half-year research on China's "platform economy"

Opportunities & challenges from Big Tech detailed by Prof. Yiping Huang

In response to key issues about the development of China’s platform economy, the National School of Development at Peking University created a task force devoted to studying innovation and supervision of the platform economy in June 2021.

This task force consists of over 20 members who come from the National School of Development, Law School, and School of International Studies of Peking University, as well as other partner universities.

Below is a November 18 presentation by Prof. Yiping Huang of the task force’s findings, which was also streamed online at the time. The translation is based on the Chinese-language text on the website of the National School of Development.

Before we go, your Pekingnologist wishes to thank Dot Dot Stand, a China tech news site, for graciously doing the key and first round of copyediting the translation. Bofei Zheng contributed to copyediting as well. All links and emphasis are added by Pekingnology.

Warning: this newsletter is very, very long.

***

Some highlights:

The advantages in China’s platform economy:

1) a market of large scale

2) low protection of rights.

3) separation of the Chinese and foreign markets

It is also noteworthy that Chinese platform companies have a huge scale, and are even at the forefront in the world, but Chinese companies lack distinct advantages in technology.

Main features of the platform economy: First, the economies of scale. Second, the economies of scope. Third, network externality. Fourth, bilateral (multilateral) market. Fifth, big data analysis.

The platform’s technical characteristics can boost economic activity in a variety of ways, which can be summarized as “three rises and three declines”. The “three rises” refer to the enhancement in scale, efficiency, and experience. The “three declines” are the decline in costs, risks, and necessary contact (some transactions can be finished in a contactless way). They improve social governance, spur economic growth, exhibit an obvious long-tail effect, generate jobs, and facilitate innovation.

Three examples of the benefits from the platform economy: First, the inclusive nature of digital finance. Second, big tech-based credit risk management. Third, the development of digital platforms may contribute to China’s macroeconomic stability.

The problems from the platform economy: Governance function; Innovation vitality; Income distribution; Fair competition; algorithm; International challenges.

As economic growth slows, concentration rises, and income distribution worsens, the public develops a growing aversion to large corporations. The three economic factors can be applied to the current situation in China to some extent.

To govern platform economy, an unavoidable question is how to identify or define monopoly? In traditional views, to see if there is a monopoly, the first step is to look at the market share of a company. However, this approach would encounter difficulties in application to the platform economy, because the basic attributes of the platform economy are the economies of scale, the economies of scope, and network externality. It means that “being big” is a defining feature of a well-performing platform economy.

The task force prefers to use the concept of “contestability” put forward by U.S. economist William J. Baumol in 1982. A monopoly should not be based on market share alone. What is important is to see whether the barrier to entry and sunk costs are low enough. There is contestability as long as these indicators are low enough. It is difficult for a platform to completely monopolize a sector, even if it has a large market share.

At the same time, there is a prominent difference between Chinese platform companies and American ones. Many Chinese platform companies have operations in many sectors.

The research task force’s recommendations:

1. The key to improving the “governance” of the platform economy is to place equal emphasis on regulation and development to boost innovation, maintain fair competition, protect consumer interests, and encourage platforms to share dividends, and ultimately achieve common prosperity.

2. Currently, monopoly might not be a prominent issue in China’s platform economy.

3. Regulatory policies should focus on regulating the behavior of platforms while also considering the attributes of the platform economy.

4. A holistic governance system with multiple dimensions including judiciary, supervision, and self-discipline.

5. It is necessary to avoid 运动式监管 campaign-style supervision.

6. Regulatory policies should be adapted to the times.

7. As special corporate entities, digital platforms should strengthen self-discipline and become responsible enterprises that take into account both economic and social objectives.

The full text begins momentarily

You are welcome to buy me a coffee or pay me via Paypal, to help make Pekingnology sustainable.

Huang Yiping: Opportunities and Challenges from the Platform Economy

What is the platform economy?

The platform economy, in our opinion, is a distinct type of digital economy. Don Tapscott, a U.S. researcher, coined the term “digital economy” in his best-selling book The Digital Economy: Promise and Peril in the Age of Networked Intelligence, which was published in 1996. The term subsequently took on different definitions.

In the《数字经济及其核心产业统计分类》Statistical Classification of Digital Economy and Its Core Sectors released by the National Statistics Bureau in 2021, the digital economy is defined as “a series of economic activities in which data resources are used as key factors of production, modern information network is utilized as an important vehicle, and information and communication technologies are employed as an important force for improving efficiency and optimizing economic structure”.

As a distinct form of the digital economy, the platform economy is a new economic model that relies on network infrastructures such as clouds, Internet, and terminals, and harnesses digital technology tools such as artificial intelligence, big data analysis, and blockchain to match transactions, transmit content, and manage processes.

Though not something entirely new, the digital platform has taken on a new scale and new connotations exhibited higher efficiency, and exerted greater influence as a result of the application of new technologies, without various constraints hampering traditional platforms, such as place, time, the scale of the transaction, and communication.

Categories of the platforms

The platforms have become an indispensable part of our daily life. According to their functions, platforms can be generally divided into two categories: 1) to promote transactions; 2) to transmit content.

The first category aims to transmit transaction information and facilitate the conclusion of transactions. Typical examples include e-commerce platforms, payment platforms, online ride-hailing platforms, and takeaway delivery platforms. Content transmission platforms primarily transmit information such as news, updates, music, opinions, and ideas, including social networking platforms and short video platforms.

We hold that current platforms will develop both vertically and horizontally. We can expect to see a brighter and broader prospect, especially in fields such as education, medical care, culture, media, furniture, wearables, and transport.

It is noteworthy that most platforms are related to personal use and consumer-oriented internet. As 5G drives the use of the Internet of Everything that provides high throughput and low latency services, we may see the rise of more new platforms based on the internet, Internet of Things, or supply chains.

There are many types of platforms, which can be grouped by different methods as in different analyses. In our analysis, only one classification method is employed.

Recently, in the 《互联网平台分类分级指南(征求意见稿)》 Guidelines for Classification and Hierarchy of Internet Platforms (Draft) released by the State Administration for Market Regulation, specific standards are set out for super platforms. For example, a platform with a market value (or an estimated market value) of more than 1 trillion yuan can be classified as a super platform. According to this standard, platforms including Alibaba, Tencent, ByteDance, Meituan, and Pinduoduo could all be seen as super platforms.

The development of platform economy

In our understanding, Taobao is China’s first platform. It was launched in June 2003, following the end of SARS in May. The story behind this is that Alibaba had conducted various matchmaking transactions, but only started to pick up momentum after Taobao was introduced.

However, it was not until 2008 that China’s platform economy took off. China’s platform economy witnessed exponential growth from 2008 to 2015, when a period of prosperity was seen in innovation and entrepreneurship. The period from 2015 to 2019 was characterized by increased competition and risks in the platform economy, which led to mergers and reorganizations. Starting in 2020, especially in 2021, we've entered a stage where platforms are being comprehensively rectified, as the platform economy met some questions including financial risks, potential monopolies, and issues regarding data and national security.

It is worth mentioning that after the outbreak of the COVID-19 last year (2020), China’s platform economy has seen faster growth.

I often mention the “broken windows theory”. In fact, political science and economics each have their own respective “broken window theory”.

The broken windows theory, a term coined by the U.S. political scientist James Q. Wilson, describes a situation in which broken glass windows in buildings along a street will induce individuals to violate social orders and damage property. In other words, visible signs of disorder and misbehavior in an environment encourage further disorder and misbehavior. For example, in daily life, if you see rubbish on the ground, you may also drop litter on the ground without feeling any shame. In a neat place, you might behave differently. This is the broken windows theory in political science and criminology.

There is also the broken windows theory in economics, which was introduced by the French economist Frédéric Bastiat. The gist is that if the glass window gets broken, it may create economic opportunities, although it is a destruction of property and is a bad thing. New economic activities take place because it entails buying glass and hiring a glazier.

The rapid development of the digital economy and platform economy in the COVID-19 pandemic can also be explained by the broken windows theory in economics. When lockdowns and isolations were the main approaches to control the spread of the virus, the distinct feature of the digital economy, namely contactless transactions, came into play. In addition, digital technologies have been instrumental in helping us identify and control risks since last year, such as those used in traveling history codes and health codes that the Chinese now frequently use.

After more than a decade of development, China’s platform economy has made great progress and occupies an important position in the world. Generally speaking, the global platform economy or the digital economy can be divided into three parts: the United States, China, and the rest of the world. As U.S. companies also dominate the market of the rest of the world, one could say that there are in fact two major players: one is the most developed major economy, which is the United States, and the other is the largest developing economy, which is China.

China’s digital economy reached 35.8 trillion yuan in 2019, accounting for 36.2 percent of the GDP, according to figures from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology. According to the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology, there are 74 digital platform companies with a global market valuation of more than 10 billion US dollars, with 35 in the United States and 30 in China. Digital platforms of the U.S. are valued at 6.65 trillion US dollars, accounting for 74.1 percent of the global total. That of China stands at 2.02 trillion US dollars, accounting for 22.5 percent of the global total. When these figures are put together, it is evident that China and the United States are indeed the two unicorn players.

“Unicorn” is also frequently mentioned when we talk about the platform economy. Unicorn companies generally refer to companies that were established less than 10 years ago and have a valuation of more than 1 billion US dollars. In early 2020, China and the United States each have five of the world’s top ten unicorns. China’s top five unicorn companies include 蚂蚁集团、字节跳动、滴滴出行、陆金所和阿里本地生活 Ant Group, ByteDance, Didi Chuxing, lu.com, and Alibaba Local Life.

Being a developing country, China was still able to occupy an important place in the digital economy/platform economy, which is by no means a small achievement.

An interesting question is, why have so many Chinese platforms developed to such big sizes? What are the advantages? China’s advantages can be summarized as below:

Advantage 1: A market of large scale. A large market has the benefit of a demographic dividend. It is easier to make innovation in a market of such a large scale, especially for platform companies as they can easily bring into play their unique advantages.

Advantage 2: Low protection of rights. In China, individual rights and data privacy are not strictly protected currently, which in a sense facilitates innovation. Of course, this also causes problems. Efforts to deal with this are now underway.

Advantage 3: market separation. There is a certain separation between the Chinese and foreign markets. As mentioned above, the platform economy and digital economy are mainly divided as China, the United States, and the rest of the world which is basically dominated by American companies. As it currently stands, these American companies do not occupy a large market share in China’s domestic market. On the bright side, this provides Chinese platform companies with room for growth and development. It also means that markets are still in fact separated.

In addition to the three advantages above, it is also noteworthy that Chinese platform companies have a huge scale, and are even at the forefront in the world, but Chinese companies lack distinct advantages in technology.

You are welcome to buy me a coffee or pay me via Paypal, to help make Pekingnology sustainable.

Characteristics of the platform economy

The main features of the platform economy are as follows:

First, the economies of scale. As we all know, adding new services onto a platform after it was established will not significantly increase its marginal cost, meaning a well-established platform can be more productive with a lower average cost. This allows the big platform to grow larger more easily at a low marginal cost. As a result, large companies can become more productive and competitive. This is the logic of the long tail effect.

Second, the economies of scope. The overall cost of producing several products simultaneously is less than that of producing each product separately. Therefore, companies are willing to engage in different business sectors. A company that produces a larger variety of products within a certain range is more efficient than one that produces a single type of product. After a platform is established, it may also delve into a variety of businesses, which is a common practice in China. For example, a platform can conduct many different businesses, such as e-commerce and payment, because of the economy of scope that comes with the platform.

Third, network externality. This is the economies of scale on the demand side. Specifically, more consumers mean a higher use value per capita. Network externality can be explained in two ways. On the one hand, as more consumers are involved, the market will expand, allowing everyone to benefit from more and better services. On the other hand, as the market grows, innovation will be encouraged, and more new services and goods are provided.

Fourth, bilateral (multilateral) market. Platforms must serve multiple parties at the same time. Takeaway delivery platforms, for example, must coordinate between restaurants, customers, and delivery riders. The pricing structure of the platform for all parties has a direct impact on its revenue. Therefore, when determining pricing for one party, a platform must take into account the external impact on other parties.

Fifth, big data analysis. Digital platforms and traditional platforms are distinguished from each other in terms of scale, speed, and data. Digital platforms can overcome the limits of time, place, and sector to become large-scale service platforms. Therefore, digital platforms hold tremendous advantages in the transmission, analysis, collection, application of information.

The platform economy’s benefits

The platform economy, which is based on technology in the platforms, can bring a slew of benefits to the economy.

Let us first turn our attention to digital technology. Why has the platform economy burgeoned since 2008? There may be a common cause for all countries around the world, namely the ongoing fourth industrial revolution. The fourth industrial revolution is a new revolution fueled by technologies including blockchain, the internet, artificial intelligence, big data, and cloud technology.

The platform’s technical characteristics can boost economic activity in a variety of ways, which can be summarized as “three rises and three declines”. The “three rises” refer to the enhancement in scale, efficiency, and experience. The “three declines” are the decline in costs, risks, and necessary contact (some transactions can be finished in a contactless way).

Here are some brief examples:

In the first example, the digital technology platform is a boost to improving social governance. Recently, the application of digital technologies represented by health codes and travel history codes to social governance and governing has become a common practice. Digital technological means, like governance instruments such as 粤省事 “Yue sheng shi” in Guangdong province and 浙里办 “Zhe li ban” in Zhejiang province, have played a significant role in helping the government improve social governance.

The second example is that the platform economy spurs economic growth. In our study, we analyzed the contribution of the digital economy to China’s economic growth and its driving force for productivity growth. Several sectors of the economy fall within the ICT (information and communications technology) production category, ICT intensive use manufacturing category, or ICT intensive use service category.

These categories can be referred to as preliminary digital economy. From 2012 to 2018, the ICT manufacturing and ICT intensive use sectors contributed 74.4 percent to China’s GDP growth. According to figures from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the digital economy accounts for about 36 percent of GDP, but the contribution of the digital economy to growth is far more than 36 percent.

In the third example, the platform economy exhibits an obvious long-tail effect. Put simply, thanks to the long tail effect, services can be provided to countless customers. Some of China’s platforms in e-commerce, payment, social networking, short video, and other areas have hundreds of millions of active users, a phenomenon unimaginable in the traditional economy.

Previously, it was difficult to provide services to such a large scale of customers, especially ordinary people, on traditional platforms. Also, long-tail services, and inclusive finance in the financial field, are also made possible as a result of the platform economy.

The fourth example concerns labor and employment. Our research team found that the prosperity platforms indeed generate jobs. On such platforms, a huge number of people run online stores, serve as delivery riders, and provide logistics services. Alibaba’s main platform includes employment for 53.73 million people; Didi spurs jobs for 13.6 million drivers; Meituan has 2.952 million riders/delivery workers. Another benefit is that these people often have flexible working hours and the threshold for employment is low. They are a new, or even important, supplement to our labor market, making a significant contribution to our labor and employment market.

The final example deals with innovation. Some argue that in addition to their own innovation efforts, such platforms can also nourish small enterprises in the platform, as they provide training, guidance, and even support to such enterprises. This will in turn benefit the innovation activities of these enterprises.

Therefore, the platform economy indeed benefits our economy in many different aspects. In addition, I would like to give three more examples.

First, the inclusive nature of digital finance.

The two maps above are obtained from the “Peking University Digital Inclusive Financial Index” research conducted by the Institute of Digital Finance of Peking University. Different colors are used to indicate the degree of development of digital inclusive finance in prefecture-level cities (the level below provinces and above counties) in China. Red indicates the most developed, followed by orange, yellow, and green. The picture on the left refers to the year 2011 and the right 2020. In 2011, only a few regions in southeastern coastal China performed well in digital inclusive finance, but in 2020, the contrast in color became much softer, indicating that regional disparities had narrowed considerably in terms of digital inclusive finance.

This can be illustrated using the simplest examples. In the past, it was difficult to have access to good financial services in remote areas and inland areas, especially in border areas. Today, however, digital finance has become widely popular. As long as we have a smartphone with a signal in our hands, we can have access to almost equal financial services, wherever we are in China. This is the basic meaning of inclusive finance we are talking about here.

Why can we make it inclusive? In fact, it is underpinned by digital technology and digital platforms. Three things, above all, sustain a platform: first, cloud technology; second, the Internet; and third, terminals. Together they make it possible for almost anyone anywhere in China to equally share similar good financial services. This is a major breakthrough.

Second, big tech-based credit risk management.

This is also an issue that I personally care about. Customers and small and medium-sized enterprises can benefit from the platform economy since it can link all customers, and conduct credit risk evaluation, and provide big tech-based lending services.

Big technology platforms and big data-based risk control are the two pillars of big tech-based credit risk management, which help acquire customers and control risks.

The main advantage of a big tech-based digital platform is its ecosystem: Platforms acquire customers by means of the long-tail effect. Customers leave a digital footprint on platforms when they shop online, socialize, view short videos, and so on. When digital footprints are accumulated, they become big data, which can assist platforms in evaluating credit risk and issuing loans. Platforms also use the ecosystem to better manage payback (of the lending). This model is being used by 网商银行 Mybank, 微众银行 WeBank, etc. to issue tens of millions of loans each year, and the overall ratio of non-performing loans can be kept low.

This business model has attracted the attention of international organizations, especially when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out in 2020. Last year, the International Monetary Fund, Institute of Digital Finance Peking University, and China Finance 40 Forum held a seminar on the big tech-based credit business model. A matter of interest to international organizations is that when quarantine and lockdown become the primary means of controlling the spread of the pandemic and all banks basically suspend their offline business, the online big tech-based credit business is still available, which is a remarkable innovation.

Third, the development of digital platforms may contribute to China’s macroeconomic stability.

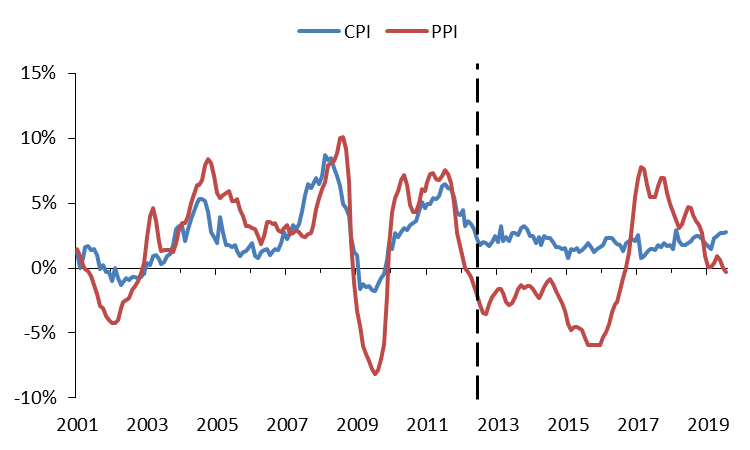

China’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) and Producer Price Index (PPI): 2001-2019

The above chart has two lines. The red line refers to the Producer Price Index (PPI), which covers raw materials, petroleum, coal, steel, and other commodities and investment products. The PPI has always had a high level of volatility. Recently, many commodities markets have been volatile around the world. China’s PPI could not stay immune from it since it has also been influenced as well. However, the blue line, which refers to the Consumer Price Index (CPI), has seen structural changes around 2013. It had nearly the same volatility as PPI before 2013, but its volatility fell in 2013 and then stabilized.

What led to such a structural change to the CPI? According to our findings, it is mainly attributed to the rapid growth of the digital and platform economy since 2013. The development of e-commerce, mobile payment, and logistics has sped up the integration of the national and regional markets, reducing CPI volatility. For example, a second-hand automobile company advertises that its customers can buy second-hand cars from anywhere in the nation - wherever the cars are cheap. In a sense, such a business model would eventually converge pricing across the country, increasing market integration, and lowering overall inflation volatility. This is also an interesting shift we did not anticipate.

You are welcome to buy me a coffee or pay me via Paypal, to help make Pekingnology sustainable.

The problems from the platform economy

The platform economy has indeed brought many benefits to the economy, but we also see some problems, which are outlined below:

Problem 1: Governance function

Regulatory bodies, markets, and enterprises can be described as three major entities in a market economy. The three work for themselves respectively, with enterprises responsible for business operations, the market for transaction matchmaking, and the regulatory body for regulation. In the platform economy, the platform itself breaks the boundaries between the three entities. It often serves the functions of enterprises (doing business), market (matchmaking), and government (regulation). The platform itself is an enterprise, and it can be said to be a new type of enterprise or economic entity.

There may be a conflict of interest between the three functions sometimes. This conflict also exists in traditional platforms such as department stores and farmer’s markets. But digital platforms are different. They feature large sizes and high speed, which enable them to provide a wealth of personalized services.

This indeed causes some problems, such as whether platforms really provide fair and just services in activities such as customer introduction and search. There are even cases of some platforms overseas attempting to influence public opinion and even election results.

How to ensure that platforms would pursue efficiency while maintaining fairness? This is a potential problem that needs to be resolved.

Problem 2: Innovation vitality

Platform companies are indisputably innovative companies, as they would not have the current accomplishments without innovation. However, after the operations reach a certain scale, can they still maintain the motivation and capacity for innovation? Many platforms hold abundant cash flow after they become bigger, acquiring many emerging innovative companies to reduce market competition. This is the so-called killer acquisition, which works against innovation.

Many platform companies quickly increase the market scale and build their market power by “burning cash”. There are successful examples (such as Didi) and failed ones (such as Mobike). If we want platforms to become one of the mainstream entities for innovation, a problem needs to be analyzed and solved: how does the platform economy affect innovation activity?

Problem 3: Income distribution

The long-tail effect applies to the services provided by platform companies and lowers the barriers to employment. Therefore, they are highly inclusive in terms of employment, service, and product provision. At the same time, they generate many jobs. It should be said that they are beneficial to income distribution.

However, platforms also kill some jobs offline while creating many new jobs related to online business. In general, new jobs might outnumber lost jobs, but it is inevitable that many people would lose their jobs and how can they weather this period of unemployment? Can they find new satisfactory jobs? Furthermore, what are the income, benefits, and working conditions for those who serve online businesses, especially delivery people? These are issues worth attention. Greater attention should be given to the issue of platforms causing excessive concentration of wealth through the economies of scale or the economies of scope over the course of their development.

The above-mentioned problems lead to a question: Will the development of the platform economy improves or worsen income distribution?

Problem 4: Fair competition

Platforms provide businesses with new venues and opportunities for competition. At the same time, there are often fierce competitions between platforms. However, is it possible that platforms exploit their economies of scale or economies of scope to form market power and increase the sunk cost for new entrants in order to restrict competition?

The "choose one from two” is an often-discussed strategy. Does this strategy stand to reason? Is it a legitimate strategy for maximizing returns on investment or improper anti-competition behavior? If it’s improper, where does it make harm?

Problem 5: algorithm

One of the reasons for the rapid growth of China’s platform economy is that personal rights and privacy are not fully protected. Improvement is being made, of course. Big data offers a wealth of opportunities and services which have not been seen before. On the positive side, it opens up opportunities for many platform companies to use big data algorithms for innovation. On the negative side, a variety of issues such as data infringement, especially privacy invasion, are prominent.

Users of platforms, particularly taxi drivers, deliverymen, and consumers, often have a feeling that they are being controlled by algorithms. The book Outnumbered: From Facebook and Google to Fake News and Filter-bubbles – The Algorithms That Control Our Lives, by the Swedish mathematician David Sumpter, demonstrates that this is a global issue.

While assisting platforms in reducing information asymmetry, big data analysis increases the information asymmetry for participants on the platform, causing problems such as “big data-based discrimination”. Therefore, what is the bottom line for implementing differentiated pricing using data algorithms?

Problem 6: International challenges

As mentioned earlier, there is a special reason for the rapid growth of China’s platform economy: the Chinese market is relatively shielded from the international market. However, China’s digital platforms will participate in international competition sooner or later, whether actively or passively. As a result, domestic regulations must take into account China’s backward technology of the platform economy, and plans must be made to bring domestic rules in line with international rules.

Europe and the United States have taken active measures in this regard. The United States’ demands for rules on “digital trade” include the free cross-border flow of data, non-localization restrictions, the elimination of digital spamming, intellectual property protection, and so on. The European Union supports the free flow of data across borders, protection of consumer privacy, antitrust, digital taxes, and so on.

Since China’s platform economy will definitely participate in international competition, how should China participate in the formulation of international rules? This is a problem we must face squarely.

You are welcome to buy me a coffee or pay me via Paypal, to help make Pekingnology sustainable.

Antitrust and “contestability”

Recently, China has become more active in anti-monopoly policy making, but this is also the case in the United States.

The U.S. antitrust policy has evolved through several stages. The Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 states that attempting to monopolize the market is wrong. This Act was implemented in the context of the establishment of some large companies in the United States, such as oil companies and steel companies, which drew some attention at that time.

In the early twentieth century, the United States tried to distinguish between “good trusts” and “bad trusts” but found it difficult to do so accurately. In 1911, the United States broke up Standard Oil. At the time, Justice Louis Brandeis of the Supreme Court of the United States stated famously the “curse of bigness”, which is both an economic and a political issue. Later, the Chicago School of economics advocated for putting consumer welfare first - the primary method is to examine prices. If the price is lower, it is a benefit to consumer welfare, and should not pose a serious monopoly problem. It may be a serious problem if prices are artificially monopolized, harming the interests of consumers. Now some Americans have returned to Brandeisism, dubbed Neo-Brandeisism - in fact, “big business is probably a problem”. It contends that in addition to economic efficiency, importance must be attached to competition, economic democracy, and so on.

Based on the evolution of the U.S. anti-monopoly policies for more than a century, we believe that active anti-monopoly policies are often associated with the emergence of three economic factors: first, the slowdown of economic growth; second, increasing concentration in sectors; third, worsening income distribution. In other words, as economic growth slows, concentration rises, and income distribution worsens, the public develops a growing aversion to large corporations.

The three economic factors can be applied to the current situation in China to some extent. China’s growth rate is slowing down, concentration is increasing, and inequality of income distribution has indeed remained serious. It can be seen from the Gini coefficient that after China’s accession to the WTO, inequality in income distribution has risen sharply.

Of course, at the time, China phased out the planned economy, and the government called for some people to get rich first. These policies inspired some people to work hard and innovate, and the economy became active fast, but inequality rose accordingly. Following the global economic crisis, our actual Gini coefficient declined but has rebounded in recent years. Generally speaking, it has been running high.

From 2020 onwards, the governance over and anti-monopoly towards the platform economy has become a major policy. The Recommendations on Formulating the Fourteenth Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) for National Economic and Social Development and the Long-Range Objectives Through the Year 2035, issued by the Communist Party of China’s Central Committee in November 2020, state that efforts will be made to promote the healthy development of the platform economy and the sharing economy as a means to cultivate strategic emerging industries.

In early 2021, the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council issued the Anti-Monopoly Guidelines of the Anti-Monopoly Commission of the State Council on the Platform Economy. On November 18, the National Anti-Monopoly Bureau was officially inaugurated.

Going forward, how should the platform economy develop? The current policies that are being seen focus on how to “govern” the platform economy, rather than “rectify” or “crackdown on” it. We believe that the purpose of “governance” should be to bring about orderly development and common prosperity.

To govern platform economy, an unavoidable question is how to identify or define monopoly? In traditional views, to see if there is a monopoly, the first step is to look at the market share of a company. Second, it’s indeed undesirable the company needs to be broken up. However, this approach would encounter difficulties in application to the platform economy, because the basic attributes of the platform economy are the economies of scale, the economies of scope, and network externality. It means that “being big” is a defining feature of a well-performing platform economy. Therefore, is the market share an appropriate indicator to determine whether a digital platform is a monopoly? We think this question warrants discussion.

When it comes to the platform economy, our research team prefers to use the concept of “contestability”. The “theory of contestable markets” was put forward by U.S. economist William J. Baumol in 1982. The theory is about how to achieve perfect competition under the premise of economies of scale. The key lies in the level of “sunk costs” for entry and exit. Therefore, the existence of contestability means the existence of potential competition pressure. A platform may have a large market scale but also face high potential competitive pressure.

For example, Taobao and Tmall, two platforms under Alibaba, had a combined market share of some 92 percent in China’s e-commerce sector in 2013, yet this figure fell to 42 percent in 2020. In just seven years, the market share drop by 50 percentage points, indicating that the e-commerce market is highly active. Despite a high market share in 2013, Alibaba did not have an absolute monopoly position. Its market share has been squeezed as a result of the emergence of many new platforms.

Therefore, we believe that whether there is a monopoly should not be based on market share alone. What is important is to see whether the barrier to entry and sunk costs are low enough. There is contestability as long as these indicators are low enough. It is difficult for a platform to completely monopolize a sector, even if it has a large market share.

At the same time, there is a prominent difference between Chinese platform companies and American ones. Many Chinese platform companies have operations in many sectors. For example, Meituan provides an online car-hailing service; Douyin is engaged in the takeaway delivery business; WeChat is engaged in e-commerce.

The table above shows that several large platforms compete in many fields. Operations across sectors have become commonplace. We hold that economies of scale and perfect competition do not rule out each other due to cross-sectoral operations and the economies of scope. In other words, large scale, however large it is, does not mean that there is no competition because there is economies of scope.

Another set of data also shows that by the end of 2020, China had nearly 200 digital platforms with a market valuation of more than US$1 billion. However, the market valuation of the top ten companies fell from 82 percent in 2015 to 70 percent. This indicates that small, medium and large-sized platforms in China are all developing apace, making the platform economy highly contestable.

However, alongside “contestability”, many platforms that participate in the competition often have investments by the same super platform. What does this mean for market competition deserves further analysis.

Thoughts on future development

After over a decade of development, China’s platform economy achieved rare achievements, which is no small feat for a developing country.

For the development of the platform economy, we give our preliminary viewpoints:

1. The key to improving the “governance” of the platform economy is to place equal emphasis on regulation and development to boost innovation, maintain fair competition, protect consumer interests, and encourage platforms to share dividends, and ultimately achieve common prosperity.

2. Currently, monopoly might not be a prominent issue in China’s platform economy. Therefore, regulatory policies should focus on reducing anti-competitive behavior, enhancing “contestability”, and cutting the “sunk cost” for the entry of competitors.

3. Regulatory policies should focus on regulating the behavior of platforms while also considering the attributes of the platform economy. For practices such as “choose one from two”, “big data-enabled price discrimination”, and bundling sales, it is necessary to make a thorough analysis of both the legitimate and illegitimate reasons behind such practices.

4. We recommend establishing a holistic governance system with multiple dimensions including judiciary, supervision, and self-discipline. Legal procedures are typically scrupulous, but also intense, costly, and late.

5. It is necessary to avoid 运动式监管 campaign-style supervision. Instead, we should rely more on “routine” and “responsive” supervision that can identify problems and correct wrong behavior in a timely manner, and meanwhile, establish an effective mechanism for appeals.

6. Regulatory policies should be adapted to the times. Digital technologies such as big data should be employed to ensure timely supervision. At the same time, measures such as “regulatory sandbox” should be adopted to balance the relationship between business innovation and orderly development.

7. As special corporate entities, digital platforms should strengthen self-discipline and become responsible enterprises that take into account both economic and social objectives. (END)

***

Lastly, let’s put a face to the presentation.