Tang Xiaoyang: Stitch Africa’s Fragmented Supply Chains with Chinese Capacity

Tsinghua professor says Chinese enterprise clusters in Africa can anchor full-chain investment and a pivot from scale to integration.

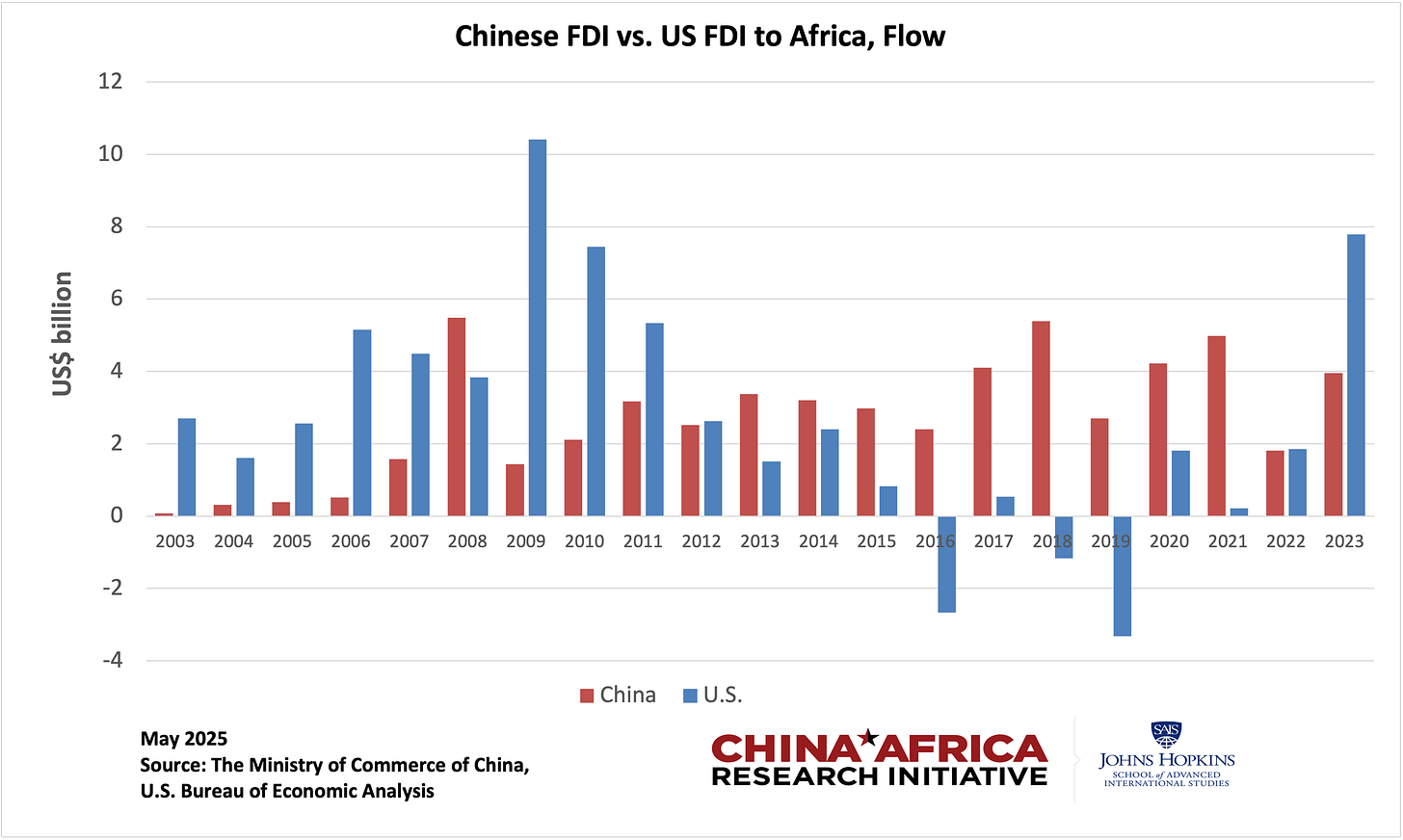

The BBC yesterday reported, citing the latest annual figures gathered by China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, that the US has actually quietly overtaken China as the biggest foreign direct investor in Africa in 2023.

A short while ago, Tang Xiaoyang, Chair and Professor, Department of International Relations at Tsinghua University, argues that although geopolitics and softer growth have cooled headline expansion in China–Africa commerce, long-standing cooperation mechanisms and complementary industrial structures make this a window to shift from scale to integration.

Leveraging the more than a dozen agro-industrial parks and clusters of Chinese enterprises already established in Africa, the leading expert on China-Africa ties says, can build full-chain capacity in mining, agriculture, and light industry.

His following article was published on Orange News, a Hong Kong-based Chinese-language news website, on September 26, 2025.

中非經貿新動向與產供鏈投資機遇

New Trends in China–Africa Economic & Trade Ties and Investment Opportunities across Industrial and Supply Chains

Since the turn of the century, under the influence of the Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China–Africa trade has grown steadily with notable resilience. According to UN Comtrade data, total China–Africa trade increased from USD 39.668 billion in 2005 to USD 295.411 billion in 2024, an average annual growth rate of 13.96%. China has been Africa’s largest trading partner for sixteen consecutive years since 2009. In 2024, China imported USD 116.8 billion from Africa, up 6.9%, and exported USD 178.8 billion to Africa, up 3.5%.

As for the current trade structure, China mainly imports primary products from Africa, such as mineral resources and agricultural products, which provide important resource support for China’s economic development. UN Comtrade data show that in 2024, China’s top three import categories from Africa were petroleum gases (HS27), ores (HS26), and copper and copper products (HS74), accounting for 28.17%, 26.94%, and 19.14% of China’s imports from Africa, respectively.

China primarily exports manufactured goods, especially machinery and transport equipment, to Africa, meeting African countries’ needs in infrastructure, industrial equipment, and consumer welfare. In 2024, China’s top three export categories to Africa were electrical machinery and televisions (HS85), boilers and mechanical appliances (HS84), and vehicles and parts thereof (HS87), accounting for 14.39%, 14.26%, and 8.24% of China’s exports to Africa, respectively.

China and Africa have highly complementary industrial structures, ensuring steady progress and win–win outcomes, especially in industrialisation. Misguided by Western neo-colonialism and neoliberal policies, Africa’s manufacturing sector long stagnated or even declined. In Sub-Saharan Africa, manufacturing value added as a share of GDP was 17.89% in 1981, fell to a low of 9.7% in 2010, and stood at only 10.65% in 2024 amid global economic turbulence and restructuring.

However, African countries are now actively promoting manufacturing. The African Union has introduced strategies such as the Action Plan for the Accelerated Industrial Development of Africa and Agenda 2063, all identifying industrialisation as key to Africa’s development. Ethiopia, Rwanda, South Africa, and others have also issued national industrial policies. China has the world’s most complete industrial system and production capacity. In 2024, China’s industrial value added accounted for 28% of the global total, and its manufacturing scale ranked first worldwide for the fifteenth consecutive year. China is able to forge industrial linkages and capacity partnerships with African countries that have weak industrial bases, and in the context of growing trade barriers against Chinese exports in Europe and the United States, Africa has become an important expansion direction for Chinese manufacturing enterprises.

China-Africa cooperation is also being adjusted in line with global political and economic changes, following a pragmatic and phased approach to find the most effective methods. First, trade and infrastructure take the lead, with both sides continuously enhancing cooperation on trade facilitation. The Chinese government has promoted African goods’ entry into the Chinese market by lowering tariffs on African countries and streamlining customs procedures. In June 2025, China announced zero-tariff treatment for 100% of tariff lines for 53 African countries with diplomatic ties with China. The two sides have also strengthened cooperation in standards, certification, inspection, and quarantine.

Cooperation in infrastructure is a key pillar of China–Africa relations. Chinese companies have financed and built numerous railways, highways, ports, energy facilities, and industrial parks in Africa, significantly improving Africa’s connectivity and economic capacity and providing the necessary material foundation for Africa’s industrial development. Drawing on China’s own development experience, China’s infrastructure efforts in Africa do not rely solely on either markets or the government, but balance commercial sustainability with public benefits. China and African countries jointly formulate plans around major infrastructure and industrial park projects to foster a virtuous cycle between infrastructure and industrial development.

Second, trade and infrastructure have deepened mutual understanding and improved Africa’s investment environment, leading to a growing number of Chinese manufacturing firms operating in Africa. Some are large export-oriented investments such as footwear, gloves, and apparel that bring foreign exchange and thousands of jobs to local communities. However, incomplete and unreliable supply chains are one of Africa’s fatal weaknesses in international competition. Most materials and components, even packaging materials, must be imported from China or elsewhere, raising production costs and complexity, weakening the competitiveness of African manufacturing, and severely constraining the growth of export processing industries.

By contrast, the number of Chinese investments targeting domestic and regional African markets far exceeds export processing projects. Some businesses, such as plastics and steel recycling, food processing, and fast-fashion garment production, can only be carried out locally. For other products, such as building materials—cement, ceramics, and steel pipes—the cost of long-distance imports into Africa is too high, so substituting imports with local production has become a market trend.

Many Chinese firms that later invested to serve local African markets had engaged in long-term trade there before committing capital. They shifted from trading to investment either after identifying unmet “gaps” that imports could not satisfy, or after concluding that local production would be more competitive than importing finished goods. Once they decide to invest, China’s vast and complete manufacturing system provides strong industrial support to investors in Africa, enabling them to quickly and affordably source appropriate machinery and technical personnel in China.

Finally, industrialisation in the broad sense also encompasses extractives, agriculture, and the telecoms/digital economy. In Africa, China has supported local mechanisation and specialisation, helping advance African industrialisation by improving processing capacity and productivity in these fields. In mining, Chinese investment has injected strong momentum into the development of African mineral resources; through advanced technology and management experience, it has raised production and resource efficiency, promoting the modernisation of Africa’s mining industry. In agriculture, China–Africa cooperation, via technology exchange and investment, has upgraded the industrialisation level of African agriculture, contributing to food security and rural economic development. In telecommunications, the active participation of Chinese companies has brought significant changes to Africa’s telecom infrastructure. Digital and telecom firms such as Huawei, ZTE, Transsion, and StarTimes operate across various hardware and software segments in Africa, enhancing ICT capabilities and facilitating digital transformation in African countries.

Amid major global geopolitical shifts, both China and Africa have faced considerable economic pressures in recent years, yet long-standing cooperation mechanisms and complementary industrial structures have endowed bilateral economic and trade ties with resilience and growth potential. Although economic pressures may temper expectations for scale expansion, this is an opportune moment to improve the quality of existing China–Africa projects and optimise their operating mechanisms.

The key to improving quality and efficiency is to integrate relevant Chinese projects across industrial, logistics, and financing chains; overcome the fragmentation of African markets; deepen China’s participation in key economic and social domains in Africa; strengthen integration between the two sides; and promote regional market integration. In particular, leveraging the more than a dozen agro-industrial parks and clusters of Chinese enterprises already established in Africa, stakeholders can identify upstream and downstream links that have the conditions and advantages for local investment and production, and attract Chinese and other firms to invest in related segments of the industrial chain. Priority areas include building integrated mineral supply chains covering exploration, extraction, beneficiation, smelting, and processing; agricultural supply chains integrating cultivation, harvesting, processing, storage and transport, and export; and light-industry consumer-goods clusters serving local markets, such as plastics, luggage and bags, apparel and footwear, building materials, and small home appliances. At the same time, logistics chains aligned with these industries should be developed to form a virtuous cycle in which infrastructure and industrial investment reinforce and safeguard each other.