Tsinghua law professors call for renewing open access to China's court judgments

Significantly fewer judgments are available on the China Judgments Online website. China's legal community is concerned.

A leaked document from China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) circulating in Chinese social media on Monday, December 11, showed that the top chamber had instructed courts across the nation to upload all their judgments to an internal database, just as the SPC’s open-access platform for judgments saw significantly fewer number of cases in the past three years.

China Judgments Online, an unprecedented judicial transparency project that promised to make available all court judgments online, with few exceptions, saw a stunning reduction of court judgments available.

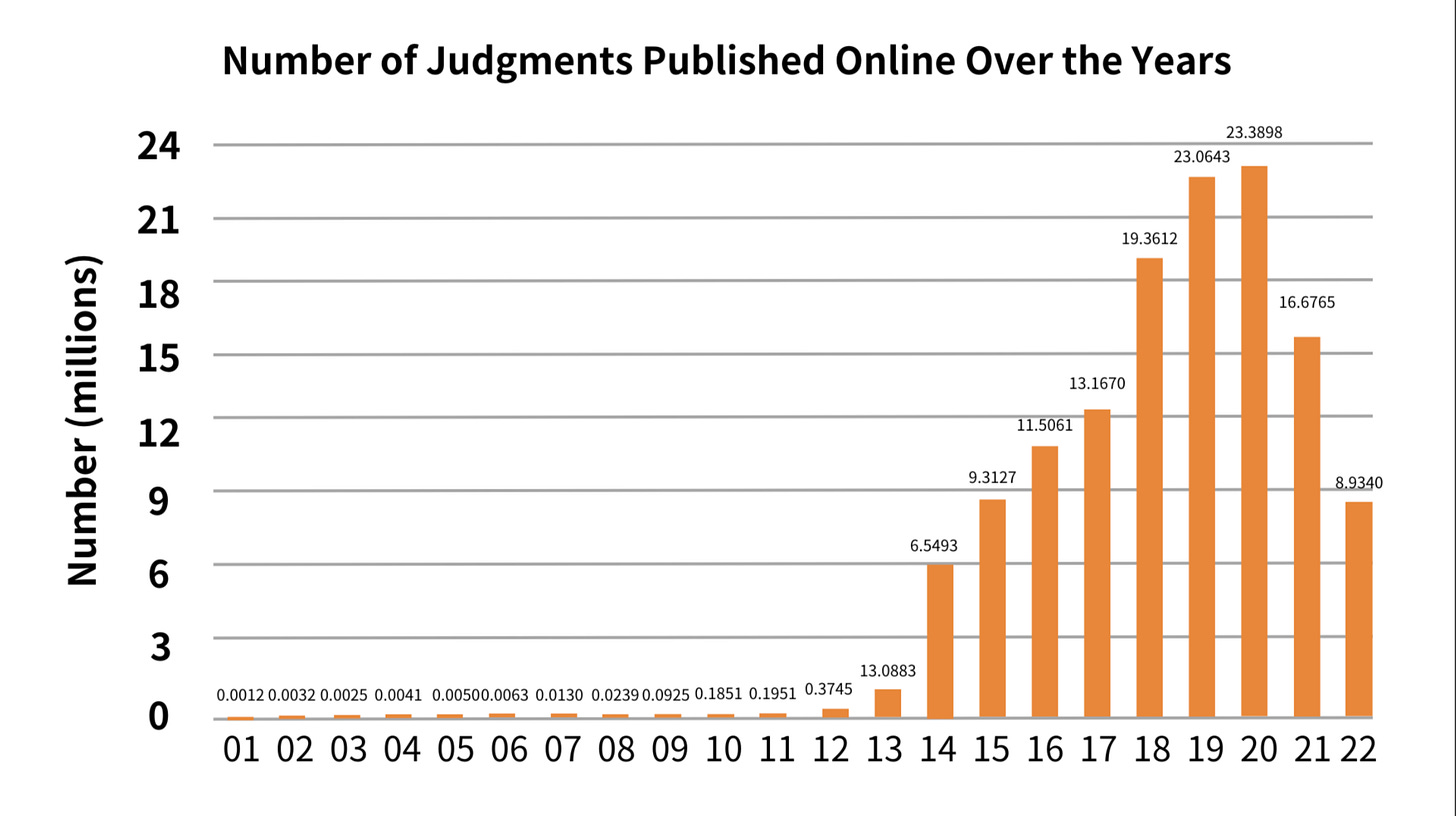

[Credit: Professor He Haibo of Tsinghua University. Translated by Yuxuan Jia.]

At its peak between 2018 and 2020, China Judgments Online registered 19 to 23 million judgments, before diving to 16.68 million in 2021 and 8.93 million in 2022. Among over 670,000 judgments of administrative litigations in 2022, only 854 were published, according to He Haibo, a law professor at Tsinghua University.

By Wednesday, December 13, 2023 the website hosted 143 million judgments and registered 107.9 billion views.

[Credit: Snapshot on Wednesday, Dec. 13, 2023. Translated by Yuxuan Jia.]

The day only saw 1,781 judgments added. At that rate, a year would see 650,000 judgments being offered online, a far cry from its peak.

The leaked document, confirmed by anonymous sources to be true by a report via Caixin, China’s leading business magazine, asked all Chinese courts to upload their effective judgments since January 1, 2021, to an internal database accessible only within China’s court system and unavailable to the general public. It was handed down by the General Office of the SPC in November 2022, according to the leaked document and Caixin’s confirmation.

The developments have prompted a huge outcry in China’s legal profession. 劳东燕 Lao Dongyan, an outspoken law professor at Tsinghua University, lamented on Weibo, China’s equivalent to X, formerly known as Twitter

China Judgments Online is going to be transformed into a database for internal reference only. Knowing this, I feel quite upset. As my colleague Professor 何海波 He Haibo said, 'It's not just regret that I feel, but heartache.' The publication of court judgments has indeed brought various problems in the short term, including the discovery of many cases of different judgments for similar offenses, which affects the credibility of the judiciary. But shouldn't such problems be addressed directly? I don't believe that hiding these phenomena from public view will enhance the credibility of the judiciary. This cannot be an effective way to solve the problem.

The large-scale public disclosure of judicial judgments will have an impact on legal research and education, but that's not the only concern. More importantly, the publication of court judgments carries the goal of the rule of law. The judiciary itself is a decisive power and, except in special cases (such as involving minors or state secrets), the facts of the case, the judgment, and the corresponding reasons should be made public as a matter of course. Only in this way, through the handling of individual cases, can the public be informed of the general rules of behavior as set out in legal norms, thus avoiding similar disputes repeatedly arising and entering the judicial system. In other words, effective social governance through law can only be achieved through the publication of laws and corresponding judgments.

My colleague Professor 何海波 He Haibo summarized the significance of the publication of court judgments in five aspects: First, it promotes judicial fairness. Judicial judgment is a matter of conscience, and transparency is the best preservative. Second, it enhances judicial credibility. Let the people see that the vast majority of decisions withstand scrutiny. Third, it clarifies legal rules. Precedents are the best explanation of the law and the best predictor of action. Fourth, it promotes social credit. Court judgments can provide information needed for market transactions. Fifth, it aids leadership decision-making. Scientific decision-making relies on good 'number management.' Those are wise words indeed.

On November 26, 王涌 Wang Yong, Director of 洪范法律与经济研究所 Hongfan Institute of Legal and Economic Studies and law professor at China University of Political Science and Law hosted a live-streamed discussion on China Judgments Online. Professor 何海波 He Haibo, of Tsinghua University, gave a presentation on the challenges facing the the world’s largest and most ambitious judicial transparency initiative. They were joined by presentations and discussions from Prof. 傅郁林 Fu Yulin from Peking University Law School and Prof. 吴宏耀 Wu Hongyao from China University of Political Science and Law.

Hongfan is a non-governmental research institution focusing on major legal, economic, and political issues co-founded by the renowned economist Mr. 吴敬琏 Wu Jinglian and the renowned jurist Prof. 江平 Jiang Ping, two widely-respected scholars on China’s economic and legal reforms, respectively.

Below is the first part of He Haibo’s presentation. Pekingnology thanks Wang Yong for providing the Chinese transcript of the live-streamed discussion - Zichen

Professor He Haibo of Tsinghua University School of Law, Nov. 26, 2023

Thank you for having me here at HILE to discuss a timely topic: China Judgements Online (CJO). You may recognize this image; I captured this screenshot in 2018 when tens of thousands of judgments were being uploaded online daily.

However, things have changed. When I checked yesterday, the platform appeared different. While the official explanation cites an ongoing site redesign, it is clear that some of the original search functionalities have been altered. The key issue is that after 2014, we witnessed a significant surge in the number of judgments available online. This number peaked in 2020 but has since experienced a substantial decline, nearly halving in volume.

Civil cases typically constitute the majority of cases and have also experienced a significant reduction in volume. However, the most substantial decline has been observed in criminal and administrative cases. As an illustration, in the field of administrative litigation, which is my area of expertise, there were over 670,000 cases concluded nationwide in 2022. Surprisingly, only 854 of these cases were made available online.

Today, I came across someone raising concerns about whether the publication of these judgements has ceased entirely. They noted that only one tax-related case was uploaded last year. But when you consider that only 854 administrative judgements were uploaded in total, it's not surprising that there was just one tax case among them.

Nonetheless, it's essential to highlight that our relevant legal provisions, as amended in the Administrative Litigation Law of the People's Republic of China in 2014, clearly state in Article 65 that "People's courts shall disclose judgment opinions and ruling that have taken legal effect, for the public to read, except for those with content touching upon state secrets, commercial secrets or personal privacy." This means that the current policy adjustments in the publication of judgments, specifically the significant reduction in uploads, do not align with the spirit of the Administrative Litigation Law.

It's crucial to note that the 关于人民法院在互联网公布裁判文书的规定 Regulations on the Publication of Judicial Documents by the People's Courts on the Internet are still in effect today and have not been repealed. This is why I find the current situation regrettable. On a personal level, my sentiments extend beyond mere regret; I would go so far as to say that I feel HEARTBROKEN. I had invested a significant amount of hope and enthusiasm into the CJO initiative.

In 2000, while studying at Peking University, I published a small piece in the 《法制日报》 Legal Daily titled 判决书上网 "Publishing Judgements Online." It was during the first wave of internet excitement, and an idea struck me, which also served as the opening sentence of my article: What if the Supreme People's Court established a website where all courts could uniformly upload and categorize their judgments? Initially, I regarded it as a mere fantasy, but soon after, the Supreme People's Court embarked on the practical implementation phase. During this journey, the Supreme People's Court continuously revised its regulations on CJO for three consecutive years, and I had the privilege of participating in some of these discussions.

Later, I led my students in conducting two comprehensive and in-depth surveys on the online publication of judgments, and we published our findings in the Hongfan Review (洪范评论). In 2019, when the initiative faced increasing pressure, I wrote an article to support the Supreme People's Court. The title of the article was 裁判文书上网公开,一件有中国特色、中国气派的事情 Online Publication of Judgements: A Matter of Chinese Characteristics and Style.

[Note by Zichen: It’s still on the SPC’s official WeChat blog.]

Therefore, considering the current situation, I am genuinely heartbroken.

Next, I'd like to discuss four key aspects:

My perspective on the online publication of judgments and its progress.

The significance of publishing judgments online.

The challenges during the online publication process.

My thoughts on enhancing this system in the future.

First and foremost, regarding the process of publishing judgments online, I want to emphasize that the process of publishing judgments online didn't occur in a vacuum. It was part of China's broader efforts to enhance transparency and openness. In fact, before or around the same time as the CJO initiative, various branches of the Chinese government were already exploring transparency measures.

For example, in 2000, the Supreme People's Court introduced the 《裁判文书公布管理办法》"Administrative Measures for the Proclamation of Document of Judgement." These measures mandated the publication of selected judgments in China Court, the Supreme People's Court's official newspaper, and on the courts' official websites.

This coincided with the government's emphasis on open government affairs. Starting from 2001, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) consistently and fully disclosed all of its administrative penalty decisions. In 2007, the State Council enacted the 《政府信息公开条例》 "Regulation of the People's Republic of China on the Disclosure of Government Information," which established a comprehensive system for information disclosure in the administrative sphere. This regulation highlighted citizens' right to access government-held information and established openness as the norm, with non-disclosure as the exception.

Following this, the Supreme People's Court issued and refined regulations on the publication of judgments for several consecutive years. Compared to the administrative system, the courts indeed moved faster and led the way. When the publication of judgments faced pressure, the openness of government information faced similar challenges.

However, the 2019 《政府信息公开条例》 "Open Government Information Regulation of the People's Republic of China" improved specific rules, further advancing the government information disclosure system. Additionally, in the legislative processes of the National People's Congress and major administrative decision-making processes, various laws and regulations were progressively promoting this cause.

Therefore, it's essential to comprehend the CJO initiative within this specific context. To what extent were judgments published online? Allow me to share some statistics from 2018, with data up to 2017. In 2017, the Public Disclosure Ratio was approximately 63%. This ratio represents the percentage of documents made public by the courts in comparison to the total number of cases concluded across various types, regions, and levels nationwide for that year. This figure is quite impressive considering that, based on Chinese legal regulations, numerous documents were not originally meant to be disclosed. However, it's worth noting that this figure is slightly inflated because some judgments were published with only basic information as required by regulations, such as the case number and date of judgment, without detailed content. When these cases were excluded, the actual Public Disclosure Ratio was close to 50%, which is still a noteworthy achievement.

Despite the progress made, there were still issues with the publication of judgments at that time. My particular concern centered around selective publication--were important cases that garnered public attention adequately disclosed? I analyzed two types of cases: media-reported high-profile cases and 指导案例 guiding cases published by the Supreme People's Court. I assessed the number of related documents published for these two categories of cases. Here's what I found:

In high-profile cases, 38% were not published at all, and some were only partially published. This means that in certain instances, you might find documents related to the second instance but not the first, or vice versa. When it comes to guiding cases, similar situations were observed, with 37% not published at all and 35% partially published. These findings highlighted that the CJO fell short of providing comprehensive disclosure in terms of substantive content.

I also investigated the timing of judgments being uploaded. Using 2017 as an example, I found that judgments issued within 31 to 90 days constituted the largest proportion, accounting for only about one-third of all published judgments. Additionally, there was a small number of judgments that were published one to two years after their issuance. This observation highlighted the need for improvement in the timeliness of making these judgments public.

Furthermore, I conducted an assessment of how effectively sensitive information was handled in the publication of judgements. The rules in place at that time clearly outlined certain elements that should not be disclosed to the public. For instance, divorce judgements were consistently kept private. In cases involving victims or minors, it was often necessary to conceal certain details before making the documents public.

However, our survey uncovered that a significant number of documents failed to properly redact sensitive information. This deficiency could have led to resistance against the CJO initiative and resulted in more information being kept from the public. Conversely, we also identified an issue in the opposite direction: at times, information that didn't warrant redaction was needlessly concealed. For instance, company names were occasionally redacted without valid justification.

Regarding the significance of publishing judgements online, I've categorized five key aspects:

(1) It promotes judicial fairness. Those of us in the legal profession understand that law is often not as clear-cut as a math problem. A judge's decision is frequently a matter of conscience. A slight bias towards one party could lead to a plaintiff's victory, while a bias towards the other might favor the defendant. The most effective way to oversee these conscience-driven decisions is not through external evaluations but by making them publicly available for scrutiny. Transparency is the optimal approach, and the rationale is straightforward: when judges are aware that their judgments may be published, they are likely to exercise greater caution in their decision-making and be more diligent in composing their verdicts. At times, judges might proactively seek relevant precedents to ensure their decisions align as closely as possible with previous cases. Even when they deviate, they must provide solid justifications. Consequently, the most significant benefit of making judicial documents available online is the promotion of judicial fairness.

(2) It enhances judicial credibility. Justice needs to be not only achieved in practice but also visibly fair and trusted by the public. China's current approach is to publish a selection of typical cases, which are understandably well-judged and correct. However, the public's real concern lies with the cases that remain unpublished. Typical cases alone cannot address this concern. Thus, only by making all judgments public can people get a true sense of the overall situation.

I am firmly convinced that once all judgments are published, people will undoubtedly recognize that the vast majority of judgments can withstand scrutiny. In other words, while not perfect, they do indeed reflect the consistent practices of judicial authorities. The rules are explicit: if a case is lost, that's the outcome, providing little room for complaint. The objective is to seek improvements in the system rather than assigning blame to individual judges for bias or corruption. Therefore, in this context, making judgments public remains the most effective way to demonstrate the reliability of China's judiciary to society. Irrespective of any criticisms that may arise after publication regarding the quantity or issues within judgments, a fundamental truth endures: the majority of China's judgments can withstand scrutiny. This should serve as the primary basis for the courts’ decision to make judgments public.

(3) It clarifies laws and rules. The law is not always straightforward, and often, simply reading statutes does not provide a comprehensive understanding of their meaning. In such cases, the most effective way to grasp the laws and rules is by examining how the courts have interpreted and applied them. Legal precedents, therefore, serve as the clearest guide to understanding these principles.

For members of society who need to make informed decisions, knowing the laws and rules is crucial. This understanding is deepened by studying past court rulings. Being aware of how similar cases have been decided in the past aids in predicting outcomes and planning accordingly. The widespread publication of legal precedents is immensely valuable for solidifying people's comprehension of laws and rules, and it exemplifies the essence of the rule of law. The rule of law, by definition, is designed to function based on established and predictable rules, and it's these judicial precedents that provide such a structured framework.

(4) It fosters social trust. Today's society is a vast community of strangers, significantly different from traditional rural communities where everyone knew each other's families for generations. In such a society of strangers, it becomes essential to determine an individual's reliability. One primary way to assess this is by checking if the person has been involved in legal disputes.

I have a relative who faced a dilemma: whether to sue someone owing him money and whether to extend additional loans to this individual. Despite the debtor's compelling stories, I conducted an online search using the debtor's name. What I discovered was eye-opening: numerous instances of unpaid debts, mostly small amounts, but some as high as several hundred thousand. It became evident that this person had a history of deceit. Only through public records could this background be unveiled.

In today's commercial society, a mature and robust market economy demands ample information for transactions. Data about an individual's creditworthiness is crucial as China sets to build a social credit system. Constructing a trust system without substantial data, particularly data from judicial rulings, and turning to whatever department to assess or define a person's credibility, is extremely unreliable. An economist even noted that even if a court's judgment isn't enforceable, the verdict still holds significance because it provides market information, from an economic perspective.

(5) It provides references for decision-making. Scientific decision-making requires effort; otherwise, it risks being a mere shot in the dark. There are people in China's court system who compose internal reference reports and conduct statistical analyses, accompanied by charts and graphs. But frankly speaking, the simple descriptive statistics currently used in these reports do not meet the requirements of scientific decision-making. The reality is, that many of the data sets used need thorough cleansing, and the study of those data requires scrutiny through scientifically sound statistical methods.

In recent years, the online publication of judgements has sparked significant academic interest, leading to numerous noteworthy studies. For instance, in Tsinghua Law Review (清华法学) which I'm associated with, dedicated two issues to this topic, featuring over a dozen articles, most of which utilized judgements published online. Here are some examples:

唐应茂 Tang Yingmao's study 司法公开及其决定因素:基于中国裁判文书网的数据分析 "The Decisive Factor in Promoting Judicial Openness: The Data Statistics of Judicial judgements" explores why some provinces disclose more than others and what factors influence this.

乔仕彤 Qiao Shitong's work 行政征收的司法控制之道:基于各高级法院裁判文书的分析 "Regulating Administrative Eminent Domain Judicially: An Analysis of judgements of Provincial Courts(2014~2015)" reveals that a significant proportion of compulsory land acquisition cases reaching provincial courts favor individuals rather than the government. But what is the nature of these judgements? And what are the reasons behind them? This would require extensive data analysis.

Another interesting study was conducted by Prof. 魏建 Wei Jian of Shandong University and his doctoral team 异地审理与腐败惩罚:基于判决书的实证分析 "The Effect for Anti-Corruption of Trial in A Non-resident Area Court: An Empirical Study of Judicial judgements", which explored the practice of trying corruption cases in courts outside the region where the offenses occurred. The findings indicated that there were no significant disparities in sentencing severity among these courts, but variations in conviction rates were observed. While courts maintained a uniform standard for sentencing severity, courts in external jurisdictions tended to adopt a slightly stricter stance on convictions, which is an intriguing observation.

胡昌明 Hu Changming's research on 被告人身份差异对量刑的影响"The Impact of Criminals' Social Status in Receiving Penalties: An Empirical Study of 1060 Criminal Case judgements" and 周文章 Zhou Wenzhang's study on刑事诉讼证人出庭 "Attendance of Witness in Criminal Procedure: an Analysis based on 80,351 Judgements," are also noteworthy.

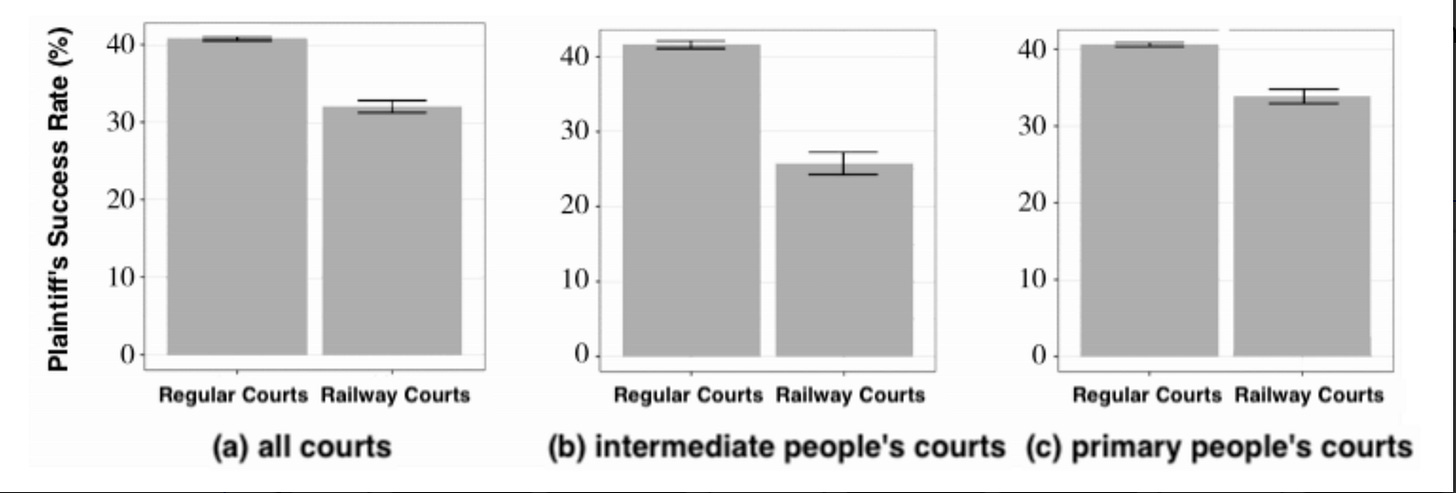

In addition, 马超 Ma Chao and I conducted a research project titled 行政法院的中国试验 "China's Experiment of Administrative Court: A Study Based on 240,000 Judgements." This study focused on the impact of the railway court's reallocation under provincial high courts in China, allowing these courts to handle specific administrative cases. This restructuring positioned them as cross-administrative region courts theoretically insulated from local government influence, potentially offering greater neutrality. This research aimed to assess whether this neutrality influenced the success rate of individuals against the government in legal cases, drawing from a dataset of 240,000 judgments. Big data research is essential in these studies because relying solely on small datasets or individual courts can be misleading, as a court's performance can vary due to factors like competent leadership or local government support. While courts like Lanzhou Railway Intermediate Court and Beijing Intermediate Court performed well, you can't get the full picture without large-scale data analysis.

I'd also like to shighlight a few studies besides those from the two issues of Tsinghua Law Review. Prof. 于晓虹 Yu Xiaohong from the Tsinghua School of Social Sciences authored a paper titled 再探人民陪审在司法治理中的作用机制:一项基于司法大数据的分析 "Re-exploring the Role and Mechanism of People's Assessors in Judicial Governance: An Analysis Based on Judicial Big Data." In recent years, China has been implementing the people's assessors system with the primary aim of allowing ordinary citizens to participate in case adjudication. The objective is to apply a dual-random selection process: randomly selecting assessors and then randomly assigning the selected assessors to cases. But is this process genuinely random? By examining millions of court documents, it becomes evident which cases the assessors have been involved in and the number of cases each assessor has participated in. Remarkably, some assessors have been involved in over 1,000 cases within two years; it's even possible to generate a nationwide list of these assessors if you're interested. This research sheds light on the existence of professional jurors who essentially work daily in the courts. Further analysis can explore the impact of jurors' participation on case adjudication.

Also, I did a study (unfinished) titled "Are the Guiding Cases being Followed?" The aim is to explore whether courts refer to guiding cases after their publication. Traditionally, this is determined by checking for citations of guiding cases in court judgments. However, there's a challenge: how can one identify cases that don't explicitly cite the guiding cases? One method involves categorizing cases and reviewing them accordingly, but this approach has limitations and can lead to significant inaccuracies. To address this issue, I enlisted the assistance of experts from the Department of Computer Science and Technology, at Tsinghua University, and leveraged natural language processing (NLP), which was quite advanced at the time. The goal is to identify the most frequently cited guiding cases.

This type of research cannot be accomplished with traditional methods; it requires big data research. Successful completion of such research relies on courts releasing sufficient data and collaboration between legal scholars and experts, particularly those trained in statistics. Additionally, it's worth noting that relying solely on traditional descriptive statistics may not yield highly reliable results.

There's a saying that goes, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics." Let me illustrate this with a study I myself conducted. This study examined the effectiveness of administrative case adjudication in railway courts. In the Chinese context, the primary measure of effectiveness is individuals' success rate in court judgments (against the government). However, to my surprise, when all the data was compiled, it was found that the individuals' success rate in railway courts was lower than in regular intermediate courts, with a significant statistical difference of 9 percentage points. In the publicly available judgments, the success rate of individuals was 42%, which is higher than the actual rate of success (I won't go into details on this). Meanwhile, the success rate in railway courts was only 32%.

Think about it, what was judicial reform initially aimed at? To have more insulated (from local government) and neutral courts like the railway courts, yet they underperform compared to others. An important reason, which is often overlooked, is the nature of the cases railway courts handle. By controlling for various variables such as case types, types of administrative actions by the defendant, and even general levels of economic development and population size in the region, it turns out that, judging by individuals' success rate, the primary railway courts' effectiveness in handling administrative cases is better than that of regular courts. However, the intermediate railway courts' performance is not as good as that of regular intermediate courts. This is a phenomenon that requires explanation, as addressed in my article with 马超 Ma Chao.

I only want to draw one conclusion here: without this kind of regression analysis and stability testing, the simple charts and graphs presented to decision-makers in China could easily mislead decision-making. That's why I stress again the necessity of disclosing judgements and the importance of close cooperation between the courts and the academic community. Only through such collaboration can leadership decisions be supported with scientific and reliable information.

Zichen’s note: It’s already way too long. Let’s get to the rest of Professor He Haibo’s presentation later.

I hope they do it right, it can costs thousands of dollars to get access to the transcript of a trial in Canada and the USA is an even bigger fragmented mess.