Who Really Owns Huawei? A response to Professors Balding and Clarke

Examining the historic and legal context in 10,000-word detail

In April 2019, Prof. Christopher Balding, then with Fulbright University Vietnam, and Prof. Donald C. Clarke, with George Washington University Law School, published a hugely influential article Who Owns Huawei?

That article, casting big doubt over China’s highest-profile tech giant Huawei’s self-claimed employee-ownership structure, received wide international press coverage at the time, leading to, for example, Who Owns Huawei? The Company Tried to Explain. It Got Complicated.on The New York Times.

Huawei responded to the article at the time, with mixed results. Your Pekingnologist had always hoped there could be a third-party, thoroughly-researched paper citing open-sourced information to examine the ownership of Huawei, preferably in the form of an academic paper and most importantly putting the question - Who Owns Huawei - in China’s particular and unique historic and legal context.

And today you can read it in this newsletter.

Your Pekingnologist came over the paper on WeChat, where it is stated the paper is on Page 211-252 in the book 《超越陷阱:从中美贸易摩擦说起》Beyond the Trap: On Sino-U.S. Trade Dispute published in January 2020, by the 当代世界出版社 Contemporary World Press. The paper is attributed to 王军 Wang Jun and titled 华为的股权与治理结构 Huawei’s Equity and Governance Structure.

A few minutes’ Googling shows Wang Jun appearing to be an associate professor in law at the Chinese University of Politics and Law in Beijing, where he works in its Institute of Company Law and Investment Protection and teaches Chinese law in its China-EU School of Law. Wang was a visiting scholar at Columbia Law between August/September 2009 to February 2010.

It’s unknown if Prof. Wang coordinates with anybody on this, but your Pekingnologist believes that’s highly unlikely, given that everything Wang wrote was based on open-sourced information and the paper, at least so far, is barely known to the English-speaking world. If Huawei or Beijing commissioned this apparently highly competent scholar to write the paper, they forgot to take advantage of it.

So it falls upon your Pekingnologist, out of his own volition and without coordination with anyone, including his employer Xinhua News Agency, Wang Jun, or Huawei to put the entire 40 plus pages into English, because he believes this is an invaluable work that will provide badly-needed value - and balance - to the prevailing and dominating narrative internationally.

You will certainly judge the paper on its own merits, but in your Pekingnologist’s view, it’s worth mentioning that:

1) The paper brings reform-era Chinese history into the discussion, and hence exhaustively lays out the origin and history of Huawei’s employee shareholding structure: where did it start? why did it start this way?

2) The paper brings Chinese law - and the limitations of Chinese law on corporate governance - into the discussion, showing why Huawei’s employee shareholding structure is probably the most viable, if not the ONLY, way for Huawei?

By answering these questions, the paper answers the key question that’s been on every concerned American mind: why is Huawei organized in such a Byzantine way? Why is it so complicated that Huawei's employee shares are held collectively through the Trade Union Committee? Why not use the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission as the "shareholding vehicle?" Why can’t it be just organized simple and straightforward like, say, Nokia and Ericsson? Is this a complicated scheme devised by Beijing - let’s be frank here, the Communist Party of China - to hide its ownership and control of Huawei, a self-proclaimed employee-owned, private business? Why don't the employees directly hold Huawei's shares and register directly as Huawei's shareholders?

3) Building on that, the paper answers the key question raised by Balding and Clarke: since Huawei’s employee shareholding is tied to a trade union (committee), and given Beijing’s leadership over the All-China Federation of Trade Unions and its lower-level braches, are those shares the employees or “trade union assets?” If Huawei’s “virtual stocks” are a contractual right, but not a property right, how meaningful are they in enabling the employee shareholders of “virtual stocks” to exercise their right to, ultimately, everything Huawei has? (A hint: remember VIE? That is also a contractual arrangement.)

Also, taking into consideration of China’s official literature, laws, and regulations, and established practice, is there substantial, believable evidence that Huawei’s employee shareholding structure, despite it being embedded/integrated with its trade union (committee), can reasonably guarantee that all those shares of this high-tech company, belong to its employees? Is it possible or how likely are higher-level trade unions, by extension Beijing, intervene?

Prof. Wang, the author, didn’t forget to take a jab at China’s Company Law adopted in 1994, in effect criticizing it as not accommodating enough domestic practice with domestic characteristics, and imposing a largely Western system of “modern enterprise” on Chinese enterprises which left them greater difficulties in fitting into the legal system.

As a foreword, this is already too long but hopefully, this sets you up for the much longer translation of 华为的股权与治理结构 Huawei’s Equity and Governance Structure, by 王军 Wang Jun. If you prefer to read the 10,000-word long paper plus its original Chinese footnotes in a standalone PDF file shared via Google Drive, please click this link. The six-part paper that most directly engages with Balding and Clarke in Part 4 and Part 5. All the content in italic is not from Prof. Wang but added by your Pekingnologist.

Again, this newsletter is a PERSONAL, UNPAID initiative where all views belong only to your Pekingnologist himself. It’s not representative of his day-job employer Xinhua News Agency, let alone the Chinese government. This piece is not representative of Huawei either - it’s just a personal translation of Wang’s published work, with minor notes from your Pekingnologist. There is no prior communication or coordination with anybody whatsoever.

In fact, this may be on the verge of possibly violating some copyrights, since the right to translate and republish the translation - though just part of the book - has not been afforded to me here. But I’ll take my chances.

***

Huawei's Equity and Governance Structure

华为的股权与治理结构

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. What are the characteristics of Huawei's shareholding and governance structure?

3. Why are employee shares held through the trade union?

4. How are the two roles of the trade union distinguished?

5. Are Huawei's employee shares equity?

6. Conclusion

***

1. Introduction

Huawei has traditionally claimed to be a private company wholly owned by its employees. [1] However, in the last decade, discussions about Huawei's equity structure have appeared from time to time in the international media. [2] The U.S. government has also shown great interest in Huawei's equity structure and Huawei's relationship with the Chinese government. In mid-April this year (2019), Christopher Balding, a professor at Fulbright University in Vietnam, and Donald Clarke, a professor at George Washington University, published an article in which they again raised the question of "who owns Huawei." [3] The two authors analyzed Huawei's shareholding structure based on publicly available information about Huawei on the Internet. The article points out with certainty that Huawei employees are not the real owners and controllers of Huawei, and that the "virtual shares" they hold are not real shares. [4] So who actually owns Huawei? The authors acknowledged that there is not enough information to give a clear answer. But they still make a bold assumption: given the close relationship between Chinese trade unions and the government, and the fact that Huawei's trade union committee holds more than 99% of the shares of Huawei Holdings, it is reasonable to assume that Huawei is a state-controlled or even state-owned enterprise. [5]

What exactly is unique about Huawei's shareholding and governance structure? Why does Huawei's employee shareholding use the trade union as the "shareholding vehicle"? Can the trade union's function as a "shareholding vehicle" be distinguished from its inherent/own function/work and role, and how? Are Huawei employees' "virtual shares" equity or not? Although these questions were raised against Huawei, their legal implications are not limited to Huawei. In fact, in the past thirty years, it has become a common mode of employee shareholding in China for employees to hold equity in companies through trade unions or employee shareholding commissions established under trade unions. [6] Therefore, responding to these questions has implications not only for Huawei but also for the practice of employee shareholding in Chinese companies. At a deeper level, the dispute around Huawei's ownership reflects the tension between the "Chinese characteristics" of (Chinese) institutional arrangements and the Western paradigm, as Chinese companies compete internationally. How can Chinese companies express their uniqueness in a way that is understandable to Western society, and how can they engage in dialogue with Western paradigms in order to promote mutual understanding and institutional improvement? The research in this paper may also be informative in this regard.

Based on a study of publicly available information (including laws and regulations, judicial decisions, Huawei's annual reports, media's public reports, and academic research materials), the main findings of this paper are:

(1) Huawei's corporate governance structure and shareholding settings are not the typical models prescribed by China’s Company Law, and their characteristics can be traced back to the practical experience and regulations regarding employee shareholding in the 1980s and 1990s.

(2) Huawei's employee "virtual shares" contain the right to participate in the company's decision-making and the right to distribute profits and residual property, which is in line with the core characteristics of equity, and is an 特殊的普通股“extraordinary common stock" constructed through agreements and internal regulations.

(3) As far as the current trade union norms and practices are concerned, the legal functions of trade unions in Chinese enterprises and their additional/added functions as "shareholding carriers" of employee shares can be distinguished de jure and de facto. The normative boundaries between employee shares held by trade unions and "trade union assets" also form/establish the legal barrier which blocks higher-level trade unions from interfering with the exercise of the rights of employee shares held by grassroots-level trade unions.

(4) In Huawei's case, the fact that the trade union committee holds 99% of Huawei's shares as a "shareholding vehicle" does not prove that Huawei is an enterprise controlled or even owned by the state, and the view that Huawei is a state-owned enterprise via trade union control is not valid.

2. What are the characteristics of Huawei's shareholding and governance structure?

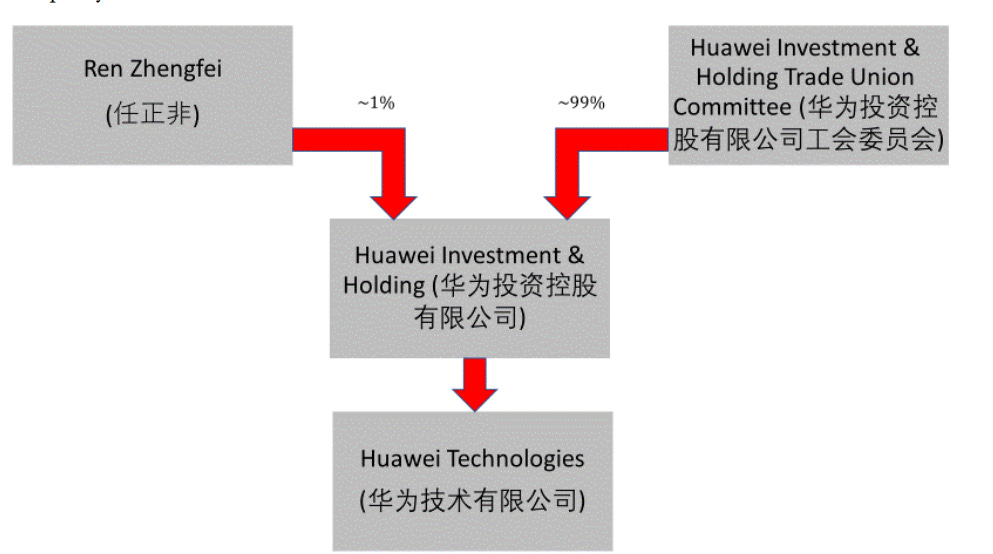

The core companies in Huawei's cluster are two companies: one is Huawei Technologies Limited (hereinafter referred to as "Huawei Technologies"), which was established in 1987, and the other is Huawei Investment Holdings Limited (hereinafter referred to as "Huawei Holdings"), which was established in 2003. According to current publicly disclosed business registration information, Huawei Technologies has at least 20 holding or participating companies and 14 branches, which constitute Huawei's production, service, and R&D entities. Currently, Huawei Holdings is the sole shareholder of Huawei Technologies, which in turn has two shareholders - the Trade Union Committee of Huawei Holdings and Ren Zhengfei, which hold 98.99% and 1.01% of the shares, respectively.

Based on the above information, Huawei's shareholding structure is illustrated in the following diagram (see Exhibit 1). [8]

Exhibit 1

Exhibit 1 (directly from Balding & Clarke) shows that Huawei Technologies is wholly owned by Huawei Holdings, which in turn is wholly owned by the Trade Union Committee and Ren Zhengfei.

Therefore, according to the provisions of the Chinese Company Law on the organization of limited liability companies,[9] it seems easy for observers to conclude that the Trade Union Committee and Ren Zhengfei, the two shareholders of Huawei Holdings, form the shareholders' meeting of Huawei Holdings, which has the authority to decide on all material matters of Huawei Holdings; since Huawei Holdings holds the entire equity of Huawei Technologies, Ren Zhengfei and the Trade Union Committee can in turn indirectly control Huawei Technologies.

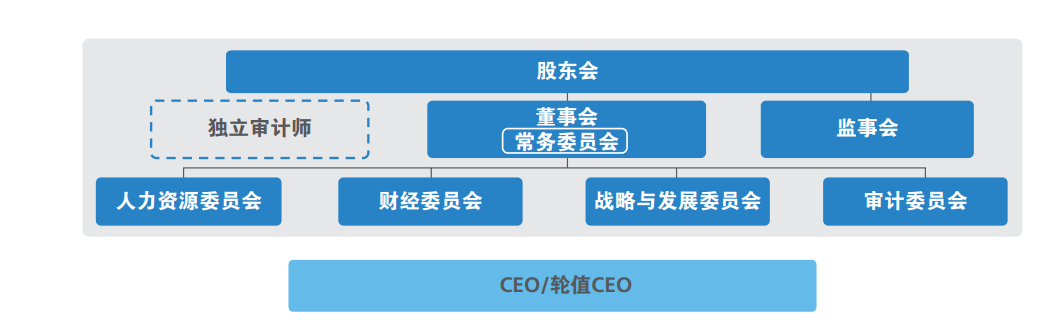

The corporate governance structure charted in Huawei Holdings' annual reports seems to confirm the outside view (see Exhibit 2). [10]

Exhibit 2

However, Exhibit 1 and Exhibit 2 actually reflect more the design of the organizational structure of a limited company under China’s Company Law and do not show the personality/uniqueness and full picture of Huawei Holding's governance structure.

First, the opinion-forming body behind the Trade Union Committee, the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission, is not shown. According to the statement of Huawei Holdings' annual report, although the Trade Union Committee is registered as a shareholder of Huawei Holdings, it is actually a "shareholding vehicle" or "shareholding platform" to achieve the employee shareholding plan, and the body which forms and expresses opinions behind the Trade Union Committee is the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission. [11] The Commission currently consists of 115 employee representatives who exercise their rights on behalf of all shareholding employees (more than 96,000 as of the end of 2018). The representatives are elected by active shareholding employees for a five-year term. [12]

The (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission in fact has some of the powers and functions of the Shareholders' Meeting as stipulated in the Company Law. [13] Huawei Holdings' annual report discloses that from 2015-2018, the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives’ Commission held one or two meetings each year, and the subjects that the meetings generally considered and approved are annual profit distribution plan, capital increase plan, corporate governance system, long-term incentive plan, etc. The meetings may also elect Directors of the Board or Members of the Supervisory Board. [14] And according to the Company Law, the consideration and approval of profit distribution plan, resolution on a capital increase of the company, and the election of Directors of the Board or Members of Supervisory Board are all among the powers and functions of the Shareholders' Meeting. [15] In order to comply with the Company Law, the above resolutions of the (Shareholding Employees Representatives’ Commission must also be confirmed by a resolution of the Shareholders' Meeting (consisting of the Trade Union Committee and Ren Zhengfei). Theoretically, it is possible for the shareholders' meeting to refuse to make a resolution confirming a decision of the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission. However, the Trade Union Committee, which holds close to 99% of the shareholders' meeting, uses the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission as the body to form and express opinions, and Ren Zhengfei is also a member of the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission. Therefore, the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission can in fact replace the function of the Shareholders' Meeting, and the "resolution adoption" by the Shareholders' Meeting afterward actually has only procedural significance.

Second, Huawei's founding shareholder Ren Zhengfei's special position in the governance structure has not been demonstrated (in Exhibit I & II) either. According to Huawei's recent public explanation, Huawei has an internal "governance charter." The charter clearly stipulates that Ren has "veto power" over the nomination of candidates for directors and supervisors, the company's capital increase plan, "capital restructuring," "governance charter," and amendments to "major governance documents." Huawei's representatives emphasized that Ren has "veto power" over some matters, but not "sole decision-making power" over all matters. [16] This allows him and the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission to form a joint-governing pattern of cooperation, as well as checks and balances.

To summarize, Huawei Holdings has adapted the governance structure of a limited company prescribed by the Company Law to its own characteristics and needs. Specifically, there are three important features.

First, the shareholding employees exercise the rights of employee shares through a "representative system". The employees holding shares are elected by the "majority of capital/stock/equity" rule of "one share, one vote" (instead of "one person, one vote"). The (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission forms and expresses the opinions of the shareholding employees and exercises the rights of the shares on behalf of the shareholding employees.

Secondly, the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission is “嵌套” embedded/integrated" in the Shareholders' Meeting and shares some of the powers of the Shareholders' Meeting which were stipulated under the Company Law. These powers (including the election of Directors of the Board and Members of the Supervisory Board, the consideration and approval of profit distribution plans, capital increase plans, governance systems, incentive plans, etc.) concern important personnel arrangements, capital and equity structure changes, internal governance systems, and profit distribution.

Third, the founding shareholder is given "veto power" on some matters, so that the founding shareholder and the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission form a type of corporate governance where there is joint governance, as well as checks and balances.

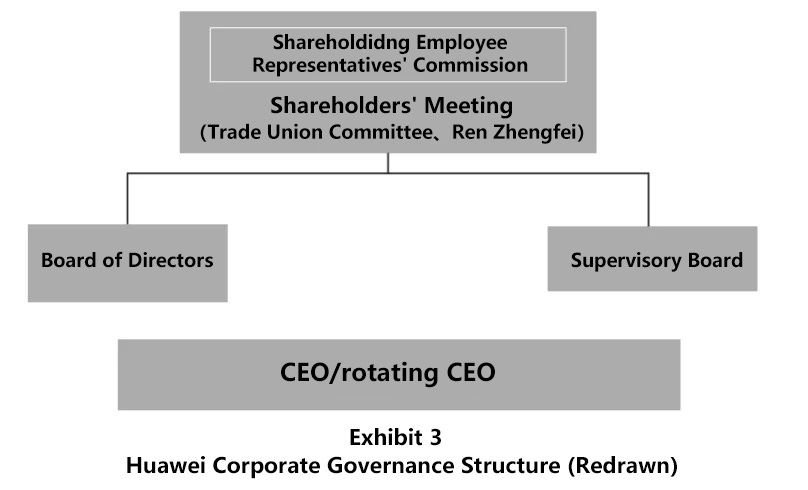

Based on the above analysis, it is necessary to redraw the governance structure of Huawei Holdings (see Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3 (originally redrawn by author Wang Jun in Chinese, translated to English by Zichen Wang with the help of Zhiyao Ma)

From Huawei's public information, we can find that Huawei's interpretation of its equity and governance structure is also gradually clearer. In its annual reports from 2013-2016, Huawei Holdings has been claiming that the Shareholders' Meeting is its 公司最高权力机构 "supreme corporate authority". The 2017 annual report changed the term of the Shareholders' Meeting to 公司权力机构 "corporate authority". The 2018 annual report continues to call the Shareholders' Meeting as "corporate authority", but for the first time positions the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission as the "supreme corporate authority." The renaming by Huawei Holdings of its Shareholders' Meeting as the "corporate authority" is in line with the official term of the law. [17] The positioning of the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission as the "supreme corporate authority" indicates that it intends to present the unique features of its shareholding and governance structure in a more comprehensive and accurate manner.

(A reminder: If you prefer to read the 10,000-word long paper plus its original Chinese footnotes in a standalone PDF file shared via Google Drive, please click this link.)

3. Why is the Trade Union used to hold employees' shares?

Why are Huawei's employee shares held collectively through the Trade Union Committee? Why not use the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission as the "shareholding vehicle?" Why don't the employees directly hold Huawei's shares and register directly as Huawei's shareholders? The following part analyzes the historical background, Huawei's own history, and legal rules.

Historical Background

In the 1980s, the practice of employee shareholding emerged in the shareholding reform of state-run enterprises. [18] The purpose of the shareholding by employees in state-owned enterprises was to improve the incentive mechanism within the enterprises, stimulate the motivation of the employees, and ultimately achieve the goal of "revitalizing" the enterprises and improving efficiency. [19] However, in the course of the "pilot", it was found that some enterprises distributed state-owned assets to cadres and employees without compensation; while pretending to/in the name of implementing employee shareholding, some enterprises issued employee shares to outsiders; and some issued employee shares were traded freely outside the enterprises. In order to prevent the "loss of state-owned assets", "abusive issuance of shares," and "illegal trading," the government issued documents to regulate employee shareholding. [20]

The legitimacy of employee shareholding in state-run enterprises is based on the fact that employee shareholding embodies the unison/union of labor and capital, which can enhance the sense of "ownership" of employees and mobilize their motivation. On the other hand, there are political and economic risks associated with the implementation of employee shareholding, such as "loss of state-owned assets," "privatization," "denial/negation of public ownership (system in China)," or "disorderly capital raising," and "disrupting the financial order." Under the combined force of both pro and con policy judgments, many normative documents of the central and local governments from the early 1990s tended to strictly control the issuance of employee shares in joint-stock companies, restrict direct and dispersed employee shareholdings, and limit the transfer and trading of employee shares. [21] One of the ways to avoid the dispersed employee shareholding is to have shareholding employees elect an "employee shareholding commission", which will collectively hold and manage employee shares. [22] In these normative documents, "employee shareholding commission" is closely related to trade unions: they are either defined as subordinate bodies of the enterprises' trade unions or can be directly registered as 工会社团法人 legal persons (as a social group by a trade union).

In 2001, Shenzhen enacted regulations on employee shareholding that did not distinguish between the ownership nature of enterprises (NOTE: whether they are state-owned, collectively-owned, or privately-owned), replacing the previous regulations that were mainly used for state-run enterprises. [23] Still, the 2001 regulations incorporated the experience of employee shareholding in state-run enterprises, listing collective management of employee shares as a model shareholding method, although it did not prohibit employees from holding shares directly in their own names. [24] Huawei's employee shareholding occurred in this historical context.

Huawei's History

Some researchers have sorted out Huawei's early days as follows: in September 1987, Huawei was registered as a 民间科技企业 "minjian science and technology enterprise" (NOTE: 民间, in Chinese pronunciation minjian, should be translated as private because it indeed means that, but this term was specifically created to circumvent the term 民营/私营 private because at the time “private” was politically problematic) with a registered capital of RMB 21,000; its shareholders included six people including Ren Zhengfei, each holding 1/6 of the equity; it had 14 employees at the time of establishment; it officially opened for business in 1988. In 1991, the number of employees increased to more than 20, and in November, the company applied for a change to a 集体所有制企业"collectively-owned enterprise", which was approved in June 1992. [25]

The above information is believable in light of the policies and regulations at the time. First, before July 1988, there was no legal basis for registering a private enterprise in China. [26] Second, in February 1987, the Shenzhen government did publish a regulation to encourage scientists to establish "minjian science and technology enterprises. [27] The "economic nature" of "minjian science and technology enterprises" is not state ownership or collective ownership, nor is it individual households, individual partnerships, or private economy per se, but a new type of ownership that diluted/evaded/blurred the issue of the nature of ownership (whether it's state, collective or private, at the time highly politically pointed in China). [28] If Huawei had indeed registered as a "minjian science and technology enterprise" in 1987, it would have been able to obtain legal status and enjoy certain tax benefits under then Shenzhen municipal regulations [29]

Why did Huawei apply to change its status to a collectively-owned enterprise in November 1991? There is no public information to explain this, and more detailed information is lacking. [30] Perhaps it was due to two considerations. First, the "private economy" still lacked sufficient legitimacy in terms of ideology, law, and policy. The status of a collectively-owned enterprise might have given Huawei a certain sense of security, although (the nature) of the ownership of the enterprise might have been blurred. [31] Second, Huawei faced a severe shortage of funds around 1991, and a collectively-owned enterprise status might help Huawei to apply for loans from state-owned banks. [32]

(NOTE: the People's Republic of China gradually and then generally considers the 公有制 public ownership system includes two sorts: 国有制 state-owned and 集体所有制 collectively-owned. In the early days of the reform era, if one company is properly recognized as one of the two sorts, then it was politically and ideologically safe/secure. You have to understand collectively-owned here does not mean privately-owned-and-collectively-owned-by-more-than-one-private-person, which, in the early days, were politically and ideologically troubling and problematic.)

Huawei initially issued so-called "internal shares" to its employees, primarily also for the purpose of financing. [33] The employees invested their capital but were not registered as shareholders of the company. According to Shenzhen's policy at the time, Huawei was eligible to apply to the municipal government to be included in a program in "joint-stock pilot" by virtue of its status as a collectively-owned enterprise, so that it could reorganize itself as a joint-stock company and issue common shares to its employees. [34] In fact, however, Huawei did not become a "pilot" and did not reorganize/convert into a joint-stock company to issue shares.

In 1997, Shenzhen published special regulations to initiate a wider pilot program for internal employee shareholding ownership in state-owned enterprises. [35] Based on this regulation, enterprises that implement internal employee shareholding should collectively manage the employee shares through the trade union (thus the employee shares are not common shares under/within the framework of the company law, and do not require industrial and commercial registration), and the shareholding employees participate in the company's decision-making through their elected representatives; [36] the employee shares are also not transferable or inheritable and should be repurchased by/sold back to the company when the employee leaves the company. [37]

Huawei wasted no time in referring to this provision and made significant adjustments to the shareholding structure: the original "internal shares'' were all transferred to the Trade Union of Shenzhen Huawei Technology Co. Ltd., which collectively owned 61.86% of the shares. [38] The other two shareholders were the Trade Union of Huawei New Technology Co. Ltd., with 33.09% of the shares, and Huawei New Technology Co. Ltd. with 5.05%. Through this shareholding reset, Huawei may have achieved at least two important goals: first, the original "internal shares'' were transformed into employee shares with the trade union as the shareholding vehicle in accordance with the Shenzhen municipal government regulation, thus achieving compliance with (Shenzhen government's regulation governing) employee shareholding, and this way of compliance does not seem to contradict the original purpose of Huawei's previous creation of "internal shares;" second, through this process, Huawei threw away its "hat" of being a collectively-owned enterprise (then, it was no longer a collectively-owned enterprise).

The restructuring of the shareholding structure in 1997 also had a profound impact on Huawei's governance structure. Huawei's practice of "嵌套 embedding/integrating" the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission with the Shareholders' Meeting was actually the brainchild of the 1997 Shenzhen municipal government's regulation on employee shares. According to this regulation, shareholding employees should elect representatives to form a shareholding commission to collectivize the management of employee shares, while some members of the employee shareholding commission should join the company's Shareholders' Meeting, Board of Directors, and Supervisory Board in accordance with legal procedures to represent the shareholding employees in the company's decision-making. [39] This is actually a "嵌套 embedding/integrating" of the employee shareholding commission in/with the "three meetings" (Shareholders' Meeting, Board of Directors, and Supervisory Board) under the company law.

On April 29 of this year (2019), a representative of Huawei Holdings explained to the outside world that the legal basis for Huawei's current implementation of employee share ownership is the aforementioned Shenzhen employee share regulations of 2001. [40] This regulation, however, does not prohibit direct ownership by employees of employee shares. Why does Huawei not adopt direct employee shareholding? Huawei's response to this is that the Company Law limits the number of shareholders in both limited companies and unlisted joint-stock companies, and it is impossible for Huawei's more than 90,000 shareholding employees to hold shares directly. [41]

This response, however, is not detailed enough to address the question. It is true that the number of shareholders in a limited liability company may not exceed 50. [42] There is no legal limit on the number of shareholders in a joint-stock company. 200 is the maximum number of initiating shareholders/promoters when a joint-stock company is 发起设立 established by way of promotion, not the maximum number of all shareholders. [43] However, if the number of shareholders of a joint-stock company exceeds 200 in the aggregate, the company is deemed to have engaged in a "public offering of securities" regardless of whether the company has in fact "publicly offered securities". [44] And for any "public offering of securities," a company must obtain prior approval from the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC). [45] Imagine if Huawei is a joint-stock company with tens of thousands of employees directly holding shares, and every year or even every month there are new and old employees increasing their shareholdings, that means each time Huawei absorbs a group of employees into its shareholding may constitute a "public offering of securities," and then Huawei needs to apply for the approval of the CSRC. Such costs are difficult to bear for any company. Moreover, a company with more than 200 shareholders is an "unlisted public company" and is subject to the full supervision of the CSRC in terms of information disclosure, internal governance, and the issuance and transfer of shares. [46] This is obviously not in line with Huawei's current development strategy, financing, and internal governance characteristics. Therefore, the legal restriction on the number of shareholders (cited by Huawei representatives to the public in April 2019) is only superficial. The key is that once the number of shareholders exceeds 200, the company (Huawei) will have to "comply" with the regulatory requirements of the CSRC for "public companies," and the company's freedom in financing and governance will be drastically reduced. And the unique and effective equity and governance structure that Huawei has developed over the years will have to be completely abandoned (in that case).

In addition to the limitation on the number of shareholders, the restriction on the qualification of shareholders is another legal reason for employee-owned enterprises to choose trade unions as the "shareholding vehicle". Trade unions can relatively easily obtain the legal person status, i.e., 社会团体法人 legal person as a social group. Chinese law and registration authorities tend to accept state investment institutions, legal persons as enterprises (later extended to include 非法人企业non-legal persons of enterprises), 事业单位 public institution legal persons and natural persons as shareholders. [47] For entities that collectively hold employees' shares, it is definitely not possible for them to register as 机关法人 "official organ legal persons" or 事业单位法人 "public institution legal persons". They can only choose between 企业法人 "legal persons as enterprise" and 社会团体法人 "legal person as a social organization."

In the case of choosing the 企业法人 "legal person as enterprise" (limited liability company or joint-stock company) as the shareholding vehicle (in law and registration), the company faces the problem of limitation on the numbers of its shareholders mentioned above. Therefore, the 社会团体法人 "legal person as a social organization" as the status of its shareholding vehicle becomes the preferred or even the only option for companies like Huawei.

The All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU), local levels of the ACFTU, and industrial trade unions naturally have the status of "legal persons as social groups", while grassroots-level trade union organizations need to apply for the status of "legal persons as social groups" in accordance with the legal person conditions stipulated in the General Principles of Civil Law. [48] (NOTE: China adopted a Civil Code in 2020 to replace the GPCL.) In addition to the fact that trade unions at all levels enjoy legal personalities/the status of legal persons, grassroots trade union committees can also apply for the status of 工会法人资格 legal persons as trade unions. [49] Therefore, in many enterprises, including Huawei, the main body representing employees' shareholding is the trade union committee.

Why doesn't Huawei directly hold employee shares through the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission? In addition to the trade union and the trade union committee, the "employee shareholding commission" within the enterprise could also, in the early days, be registered as a 社会团体法人 legal person as social groups, which could be used as the "main body of shareholding" to hold employee shares. However, the Ministry of Civil Affairs, which is responsible for the registration of social organizations, stated in July 2000 that employee shareholding commissions are "internal organizations" and do not meet the legal requirements for registration as social organizations, and therefore no longer approved the registration of employee shareholding commissions within enterprises as social organizations. [50]

(A reminder: If you prefer to read the 10,000-word long paper plus its original Chinese footnotes in a standalone PDF file shared via Google Drive, please click this link.)

4. How to distinguish the two roles of trade unions?

It is not difficult to find that the trade union acting as a vehicle of employee shareholding is somewhat contradictory to the trade union's original job and legal positioning. For example, how to reconcile the need to defend the "legitimate rights and interests" of the entire workforce, with the need to represent the interests of employees in a company where only some employees participate in a shareholding plan? Trade unions at all levels are subject to the leadership of higher-level trade unions. [51] When the instructions of higher-level trade unions contradict the demands of shareholding employees, how should the trade union, as the vehicle of shareholding, handle the situation? Also, trade unions have their own funds and properties, how can these trade union funds and properties be distinguished from employee shares held by the trade unions and not affect each other?

On how to coordinate the two roles, Huawei had two responses on April 29, 2019. First, the trade union committee is only a "shareholding vehicle"; the body to exercise the rights of shareholders of employee shares is the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission. The functions of the trade union committee and the Representatives' Commission are separate and independent from each other. [52] Second, the higher-level trade union does not interfere with Huawei's business affairs through the trade union at Huawei. The working relationship between the trade union at Huawei and its higher-level trade union are mainly: registering the legal person (status of the trade union at Huawei) with the higher-level trade union, accepting the "annual audit" of the higher-level trade union, and paying membership fees to the higher-level trade union. Other than that, there is no further connection. Huawei's trade union is not required to report to its higher-level union on the operating situation of Huawei. [53]

There are three main legal issues that need to be discussed here.

First, under current Chinese law, is it feasible for a subject (the trade union committee), registered as a shareholder, to only act as a passive, inactive "shareholding vehicle" and not to intervene in the company's business decisions, but to let another entity (Representatives' Commission) decide the company's affairs?

Second, as a "shareholding vehicle" of a certain entity, are the shares held by it (on behalf of employees) its own assets? Specifically for Huawei, are the shares held by the trade union committee in the name of the employees "trade union assets," and should they be transferred to the higher-level trade union if the Huawei trade union is dissolved?

Third, is there any conflict between an enterprise union's obligation to obey the leadership of a higher-level trade union and its role as a vehicle of employee shareholding? Can the two be legally independent of each other and not interfere with each other, as Huawei's representative said?

The analysis of the above questions is as follows.

First, Chinese law does not prohibit shareholders from holding shares on behalf of others. And the court will not hold that the contract which allocates the rights and obligations of shareholders between the "nominal shareholder" and the "actual contributor (of capital)" legally invalid simply because a shareholder is merely a "nominal shareholder" (aka "shareholding vehicle"), who holds shares on behalf of others. Therefore, to have an entity that, despite being registered as a shareholder, only acts as a passive, inactive "shareholding vehicle" is feasible under current Chinese law.

In the case that the nominal shareholder holds shares for the actual contributor (of capital), the nominal shareholder and the actual contributor typically enter into a contract to agree on the rights and obligations of both parties. The main content of the agreement is usually: the actual contributor makes the investment and enjoys all the shareholders' rights and interests, and the nominal shareholder acts on behalf of the actual contributor for the benefit of the actual contributor, or according to the actual contributor's instructions. The position of the Supreme People's Court on such contracts is that as long as there is no cause of invalidity as stipulated in Article 52 of the Contract Law, the People's Courts shall find the contract valid and support the parties to claim their respective rights according to the contractual agreement. [54]

Therefore, if Huawei establishes a contract of proxy shareholding between the trade union committee and the shareholding employees in some form (e.g., "governance charter," "Huawei Basic Law," "share subscription agreement," etc.), this contract is protected by law, provided that the content of the agreement does not violate Article 52 of the Contract Law. [55]

Second, according to the opinion of the Supreme People's Court, the "nominal shareholders" are not the real owners of the shares in their names. [56] According to the regulations and actual practice of trade union assets management, the employee shares held by the union as a "shareholding vehicle" are also not "trade union assets," so the employee shares held by the union should not be transferred to the higher-level union when the union is dissolved.

In their analysis of whether Huawei's employee shares are real equity, Balding and Clarke argue that 99% of Huawei Holdings' equity is registered in the name of the trade union committee and that employees holding shares do not have the ultimate right to benefit (i.e., the right to the remaining/residual assets) from the shares held by the trade union committee on their behalf. They argued that if Huawei Holdings was dissolved and consequently its trade union liquidated, the shares held by the trade union committee should be handed over to the higher-level trade union as "trade union assets" instead of being distributed to the shareholding employees, according to the rules of trade union asset management. [57]

NOTE: from Balding & Clarke, where TUC = trade union committee

...the insubstantiality of employee stock interests in any real sense can be shown by asking where the Huawei Holding TUC’s assets would go if it were to be dissolved. If Huawei Holding TUC were like a holding company, with the employees as shareholders, then it is clear that after debts were paid off, any residual would go to the employee shareholders in proportion to their shareholdings.

But that is not what happens when a trade union dissolves for any reason (for example, dissolution of the company where the trade union existed). Instead, residual assets of a trade union go up, not down, to the trade union organization at the next highest administrative level. 34 Employees have no claim to trade union assets. That is a very odd kind of ownership.

……

Thus, if Huawei Holding is 99%-owned by a genuine Chinese-style trade union operating the way trade unions in China are supposed to operate, it is in a non-trivial sense state-owned. Unions in China are essentially state bodies, and, as noted above, if a trade union is liquidated, its assets go up to bodies that are closer to the central state, not down to individuals. If it is not owned by a genuine trade union operating the way trade unions in China are supposed to operate, then surely it is for Huawei to make this case. The information necessary to do so is in Huawei’s control.

However, the authors' reasoning ignores an important fact: at the normative and factual level, employee shares held by trade unions as "shareholding vehicles" are not "trade union assets."

First of all, the "trade union assets" defined in the 《工会财产管理暂行办法》Interim Measures for the Management of Trade Union Property (NOTE: as quoted as Footnote 34 on Page 9 in Balding & Clarke) do not include employee shares held in the name of the union. The trade union assets defined in this document are roughly divided into two categories: one is the physical assets possessed and used by the trade union; the other is the assets of the enterprises and institutions 投资兴办 invested and started by the trade union, that is, the assets of 工会企事业 "trade union enterprises and institutions." [58] For the employee shares held by trade unions as a shareholding vehicle, the capital comes from employees' investment, rather than trade union funds or property; dividends (from the employee shares) are issued to employees rather than becoming the income of the trade union, so employee shares are not "trade union assets" which would have to be formed by investments from the trade union using its own property and assets. Usually, Chinese trade unions set up enterprises to provide cultural and welfare services for employees, generate income or place surplus staff (such as 工人文化宫 workers' cultural palaces, 俱乐部 clubs, 体育场馆 stadiums, 疗养院 sanatoriums/hotels, 旅行社 travel agencies, etc.), and the nature of the enterprises is 社团集体所有制企业 "collectively-owned enterprises by social groups." [59] The implementation of employee shareholding in a limited liability company, with the trade union as the shareholding vehicle, will not result in the company becoming a 集体所有制 "collectively-owned" 工会企业 "trade union enterprise." Therefore, there is no legal basis in saying that the employee shares held by Huawei's trade union committee are "trade union assets."

Secondly, the All-China Federation of Trade Unions (ACFTU) does not in fact consider the employee shares held by the grassroots-level trade unions to be trade union assets. From the data of national trade union assets released by the ACFTU, the assets included in their statistics are divided into two categories: 工会行政性资产 "administrative assets of trade unions" and 工会企事业资产 "assets of trade union enterprises and institutions", and "assets of trade union enterprises and institutions " cannot/do not include the employee shares held by the grassroots-level unions as a shareholding vehicle. [60]

NOTE: This is from footnote 60. In the "Report on the Supervision and Management of National Trade Union Assets in 2017," by Li Qingtang, a senior official of the ACFTU, on China Trade Union Finance and Accounting (Page 6, Issue No. 5, 2018), it is disclosed that in FY2017, the total assets of trade union enterprises and institutions above the county level nationwide amounted to 51.918 billion yuan, with total revenue of 14.895 billion yuan. And Huawei's total assets and sales revenue in FY2017 far exceeded the above statistics, which is 505.225 billion yuan and 603.621 billion yuan, respectively. (Huawei Holdings 2017 Annual Report, p. 7). It can be concluded that the All-China Federation of Trade Unions does not in fact include the employee shares held by the grassroots-level trade union at Huawei (as well as the employee shares of other similar companies) in the scope of trade union assets.

Since employee shares held by trade unions are not "trade union assets", the hypothesis that employee shares must be transferred to higher-level trade unions when trade unions are dissolved cannot be established. [61] A further argument based on this hypothesis, namely, that the employees have no residual claim on the union's shares, is also not valid.

Finally, employee shares are not "trade union assets," and if a higher-level trade union interferes with the exercise of employee share rights based on its leadership of the grassroots-level union, then that higher union is abusing its authority and there is no legal basis for its interference.

The Balding & Clarke article, based on research literature on Chinese trade unions, points out that the election of union officers, the leadership of the CPC over the unions, and the administrative rank and source of pay of union officers are evident that unions at all levels in China are under the leadership of the CPC and are de jure and de facto governmental bodies that implement state policy. [62] On the basis of this observation, the two authors further reasoned that if the Huawei trade union operated like other trade unions in China, then the trade union committee's 99% stake in Huawei Holdings would mean that Huawei Holdings was effectively owned and controlled by the state in an extraordinary way. [63]

However, the two authors seem to equate or imagine the kind of enterprises such as Huawei, where the trade union is the vehicle for employee shareholding, as a trade union-invested "trade union enterprise." The latter is indeed owned by the trade union, and the trade union is the real owner of the enterprise, which indeed exists and operates for the union's purposes. However, the situation is quite different when the union is only the vehicle of the shareholding.

From the historical background of the functions of trade unions under the Trade Union Law and their role as vehicles of employee shares, it is clear that acting as a vehicle of shareholding is apparently not the intended job of a trade union at an enterprise, let alone its main or basic function. Acting as a vehicle of shareholding is only a marginal additional function of trade unions at enterprises, formed under specific/certain historical and legal conditions. According to the regulatory rules of trade union properties, the employee shares held by the trade unions are not "trade union assets". The ACFTU does not, in fact, manage or count employee shares held in the name of trade unions as "trade union assets". Therefore, if the higher-level trade unions interfered with the affairs of the enterprises' employee shares based on their leadership over the grassroots trade unions, it would obviously be an improper act beyond their competence.

Therefore, even if the Chinese trade union system is under the leadership of the CPC and has some public functions, it is still an improper and abusive act for the higher-level trade unions to use their leadership over the lower-level trade unions to interfere with the exercise of employee shares in enterprises. Such behavior is unwelcome, contrary to the agreement between the parties and accepted practices. an objective and credible assertion about the ownership of an enterprise in which the trade union holds employee shares can not be reached based on the (hypothetical) behavior which is improper and extraordinary,

(A reminder: If you prefer to read the 10,000-word long paper plus its original Chinese footnotes in a standalone PDF file shared via Google Drive, please click this link.)

5. Are Huawei employee shares equity?

Are Huawei employee shares equity? The answer to this question depends on how we define "equity."

As the previous analysis shows, Huawei employee shares are not standard common shares of a limited liability company or a joint-stock company in the sense of China’s Company Law. Huawei does not deny this, and they refer to their employee shares as "virtual shares." [64] However, Huawei also disagrees with Balding & Clarke's article. Huawei believes that its employee shares are not a profit-sharing mechanism. Because the shareholding employees actually invest their capital, the employees not only share all the company's profits, but also bear the risk of the company's losses, and the shareholding employees exercise their shareholder rights through the (Shareholding Employee) Representatives' Commission. In addition, the shareholding employees have the right to distribute the remaining/residual property. These are not features of profit-sharing plans. [65]

In the view of this paper, Huawei's "virtual shares" are actually an 特殊的普通股 "extraordinary common stock."

First of all, in terms of the structure of rights, it is not a preferred stock or a bond but conforms to the characteristics of common stock. Employees holding shares have the right to participate in decision-making, share profits and distribute residual property. Therefore, it is not a preferred stock that has no voting rights and has a fixed percentage of dividends and priority in the order of dividends. It is not a bond, because when the company does not have distributable profits, the shareholding employees do not receive dividends either.

Secondly, it is different from common stocks, but is an "extraordinary common stock." It is extraordinary in the following ways: (1) the shareholding employees are not registered as shareholders of Huawei Holdings according to the Company Law, but hold the standard common stocks of Huawei Holdings in the name and through the shareholding vehicle of the trade union committee; (2) the voting rights of the shareholding employees are not exercised in the Shareholders' Meeting of Huawei Holdings, but through a "representative system" in which the (shareholding employee) Representatives' Commission forms and expresses opinions on behalf of all shareholding employees, which are then confirmed as corporate resolutions through Shareholders' Meetings; (3) employee shares are not transferable, and employees can request the company to repurchase a portion of them each year if they need to cash them, and when an employee leaves the company, the company usually repurchases his or her stocks unless the employee's shareholding time and age reach a certain number of years; [66 ](4) “virtual shares” are not a type of share under China’s Company Law, and the legal basis for its existence and the content of its rights are based in agreements between the shareholding employee and the company, which may take the form of a participation agreement, internal company regulations, etc.

Huawei has created this flexible "extraordinary common stock" by superimposing a "shareholding vehicle" on top of the types of shares prescribed by the Company Law. Compared with the equity or shares in the Company Law, the flexibility of "virtual shares'' is at least in the following aspects: (1) the number of holders of "virtual shares" is not limited, and that even more than 200 people own “virtual shares” do not constitute a "public offering of securities"; (2) No prior administrative governmental approval is required to increase the number of "virtual shares," so it can respond to the company's capital raising needs in a timely manner, and there is no need to change the company's registered capital with each additional batch of "virtual shares;" (3) "virtual shares" are tied to the identity of employees and cannot be freely circulated, thus avoiding frequent fluctuations in share prices and "hostile takeovers" by outside investors; (4) the repurchase of "virtual shares" does not affect the company's share capital and is not subject to the share repurchase rules of the Company Law, and the company can set its own repurchase rules; (5) the voting rights of "virtual shares" are exercised only at the level of the (shareholding employee) Representatives' Commission, which in turn reduces the possibly very high collective decision-making costs that may result from employees' direct ownership of the company's common stocks. [67]

In retrospect, these features of Huawei's employee shares can be traced back to the practice of employee share ownership in the 1980s and 1990s. The common practice at that time was that employee shares were held collectively by a trade union or shareholding commission, the shareholding employees elected representatives to exercise their rights, and employee shares were tied to employee status and restricted from being transferred. [68] The Company Law, adopted in 1994, does not reflect these practices. The Company Law only provides for the "most standard" and "clearest" as well as the "most homogeneous" governance structure and shareholding type envisioned by the legislator and does not incorporate those that have been developed in practice and reflected in many central and local regulatory documents. However, the Company Law also did not completely terminate the existing regulatory documents and practices. [69] Thus, a complex system of corporate regulations was in fact formed: laws, rules, and regulations formulated at different times existed simultaneously, with specific rules overlapping and interlocking, some conflicting and some complementing each other. Huawei employee shares are interspersed in such an intricate legal maze, seeking maximum legal space to meet corporate financing and employee incentive goals.

If we define "equity" as a collection of investors' rights to participate in the company's decision-making, profit, and residual property distribution, then Huawei's employee shares are certainly a kind of equity. However, it is not a standard common stock in law, but an "extraordinary common stock" based on a contract. Therefore, Huawei's claim that it is a "100% employee-owned private enterprise" has a basis in facts and law.

Is it legally reliable to rely on "extraordinary common stock" that is supported by agreements and internal rules between the company and its employees, different from the type of shares in the Company Law? There have been similar questions about Huawei's "virtual shares." [70] Balding and Clarke went further and denied that Huawei's employee shares are a kind of equity on the grounds that the rights enjoyed by employees are only a contract right, not a property right. [71]

The doubts of the outside world are not unfounded. The Company Law provides a ready-made legal framework for shareholders to exercise and defend their rights. Some shareholder rights within this framework do not allow corporate participants to cancel or restrict them by agreement. [72] This clearly helps shareholders to defend their rights. "Virtual shares" are not standard common shares in the sense of the Company Law, and employees holding shares are likely unable to assert their rights under the rules of the Company Law. [73] However, the contractual relationship between the employee holding "virtual shares" and the company is protected by (NOTE: other, for example, contract) law, and the contractual rights and obligations of both parties can also be argued through litigation. [74]

So, is the legal enforceability of a shareholding based on the contractual agreement, which is not readily-prescribed in the Company Law, weaker than that of a shareholding based on the statutory type of shareholding? Or, to invoke the essence of Balding and Clarke's paper, let’s ask: which is more legally enforceable, equity in the nature of a contractual right (i.e., the equity that does not conform to the statutory type but is constructed by contract) or equity in the nature of a property right (i.e., the equity that conforms to the statutory type)?

From a practical point of view, the strength of enforceability of these two types of rights cannot be generalized. Equity interests in the nature of property rights may also be unenforceable and difficult to remedy. Suppose an investor holds an equity interest in a limited liability company that fully complies with the rules of the Company Law, but his or her shareholding puts him or her in an absolute minority (e.g., less than 1/3 of the shareholding). Then, his or her right to participate in decision-making on major corporate matters, profit distribution, etc., will almost always be overwhelmed by the hands of an absolute majority of shareholders (e.g., with a shareholding of more than 2/3). [75] The company may not distribute profits for years, the company may not agree to his or her demands of capital reduction or share withdrawal, and his or her intended transfer of his shareholding to the outside world could receive no reply. He or she may file a lawsuit to ask for the repurchase of his or her equity or to force the dissolution of the company under the Company Law, [76] which may also not be upheld by the court because the statutory conditions are not met. In such a case, what is the practical significance of the investor's ownership of "property rights" even if it is 100% in compliance with the Company Law?

Contractual rights may be well enforced. Many Internet companies in China have obtained financing from abroad through so-called Variable Interest Entity (VIE) structures. Under this structure, the foreign institutional investor does not own the "property rights" of the domestic Internet business entity, but rather establishes a wholly foreign-owned enterprise in China, and then uses a series of contracts between the foreign enterprise and the business entity and its shareholders to achieve management control over the business entity and capture profits. [77] What foreign investors own is "contractual equity." The VIE structure is widely used by foreign-financed Internet companies. [78] This fact alone suggests that the "contractual equity" in the VIE structure is legally enforceable. Of course, there is some dispute about the legality of the VIE structure and the possibility that the contracting parties may violate the contractual agreement to the detriment of the other party to the contract. This is an inherent risk of "equity of contractual nature" in the VIE structure.

The above analysis shows that both "property rights'' and "contractual rights" are subject to costs in realizing their rights. In a specific scenario, a participant weighs the two costs and chooses the less costly right to achieve his or her goals. It is impossible to (generally) say which is more legally enforceable, "contractual rights'' or "property rights", not taking into consideration the specific facts/scenario.

6. Conclusion

A careful analysis of the information disclosed in Huawei Holdings' annual report reveals that Huawei's corporate governance structure and shareholding settings do not exactly replicate the typical model set by the Company Law, but have Huawei's own characteristics.

In terms of corporate governance structure, Huawei Holdings has adopted a series of agreements and regulations to build a unique structure in which the trade union committee is the "shareholding vehicle" of employee shares, and the (shareholding employee) Representatives' Commission is "embedded/integrated" in the Shareholders' Meeting and shares some of the important statutory powers of the Shareholders' Meeting. In particular, the founding shareholder of the company enjoys "veto power" on some matters, forming a pattern of joint governance as well as checks and balances with the (shareholding employee) Representatives' Commission. By using the trade union committee as the "shareholding vehicle," Huawei is free from legal restrictions on the number of shareholders, which not only achieves the goals of flexible financing and motivating employees but also avoids the various costs that may arise from "going public." At the same time, the collectivized shareholding approach also eliminates the difficulties of decision-making that may result from direct employee shareholding and enhances management's control. In this sense, it is more realistic to say that Huawei is controlled by the management rather than by the trade union.

Huawei's employee shares are different from the common shares of limited liability companies or joint-stock companies under the Company Law, and are an "extraordinary common stock." The rights of the holders of "virtual shares" can be exercised through the (shareholding employee) Representatives' Commission, and the company's resolutions are formed through the "embedded/integrated" structure of the (shareholding employee) Representatives' Commission and the Shareholders' Meeting. Its legal basis is built up by the agreements between the employee and the company, and the internal regulations of the company. Although the employees holding "virtual shares" cannot exercise the rights of shareholders in the name of shareholders as stipulated in the Company Law, their contractual rights are protected by law and are actionable. Whether the employees holding "virtual shares" can exercise their rights to participate in decision-making, profit distribution, and residual property distribution through "virtual shares" depends on the operability and legal enforceability of the relevant agreements and internal regulations, and is not related to whether the "virtual shares" are the type of shares stipulated in the Company Law or not. It also has nothing to do with whether the "virtual shares" are the type of shares stipulated in the Company Law, whether they are registered in the industrial and commercial register, or whether they are "property rights." If we define "equity" as a collection of investors' rights to participate in decision-making and to distribute profits and residual property, then Huawei's employee shares are certainly a form of equity. Huawei's claim to be a "100% employee-owned private enterprise" has a factual and legal basis.

Huawei's institutional arrangements are not entirely its own original creation. In the 1980s and 1990s, the practice of employee shareholding gradually developed into the customary practice of trade unions holding employee shares on behalf of employees and restricting the transfer of employee shares. The special rules for employee shares set by Shenzhen's 1997 employee shareholding regulation included the arrangement of "integrating/embedding" the employee shareholding commission with a company's "three meetings" (Shareholders' Meeting, Board of Directors, and Supervisory Board). However, when the 1994 Company Law reintroduced the Western corporate and shareholding system (the so-called "modern enterprise system") to China, the legislature viewed employee shareholding as a transitional, non-standard institutional arrangement and therefore did not set up rules in the Company Law to accommodate employee shareholding. However, the 1994 Company Law also did not completely terminate the original regulations or the practice of employee shareholding. Thus a pattern of a single governance structure and shareholding type on the Company Law and diverse methods of employee shareholding in local regulations co-existed as a matter of fact. Since Huawei does not seek a public listing (which would have bound it for other rules of the Company Law), it does not have to abandon the employee shareholding model to accept the governance structure and shareholding type designed by the Company Law. Huawei's approach is to build as much legal space as possible to meet its financing and management needs in the midst of complex legal regulations.

The existence of a trade union committee holding employee shares in Huawei's shareholding structure is the key factual basis for Balding and Clarke to make the inference that Huawei is owned by the state. Still, their inference ignores several important facts. First, from the historical and legal background of the Trade Union Law's positioning of the union's functions, and its role as a vehicle of holding employee shares, it is clear that acting as a vehicle of shareholding for employees is not the intended job of trade unions in Chinese enterprises, let alone its primary or basic function. The trade union acting as the "shareholding vehicle" for employees is a marginal additional function of the trade union, formed under specific historical and legal conditions. Secondly, according to the general rules in the judicial interpretation of the Supreme People's Court and the current trade union property norms, the employee shares held by trade unions in Chinese enterprises are not "trade union assets'', and the All-China Federation of Trade Unions does not include the employee shares held by the trade unions in Chinese enterprises into the management of "trade union assets". Therefore, in the event that the trade union is dissolved, the view that the employee shares held by the trade union shall be transferred to the higher-level union ("go up, not down") is without legal or factual basis. Thirdly, based on the above two points, although it is not totally impossible that the higher-level trade unions would interfere with the exercise of the rights of employee shares based on their leadership of the grassroots-level trade unions, or that the leaders of the trade unions in these Chinese enterprises would try to change from passive shareholders to active shareholders, it would indeed be a drastic challenge to the multiparty agreements and accepted practices. With the existing order largely stable, the likelihood of that happening is very low.

Thus, even if Huawei's trade union were to function like most trade unions in China, it would still be legally and factually distinguishable between its original (intended) job as a trade union and its additional function as a vehicle for employee shareholdings. The normative boundary between trade union-held employee shares and "trade union assets" also constitutes a legal barrier that blocks higher-level trade unions from interfering with the exercise of the rights of the employee shares held by grassroots-level trade unions holding them. The fact that the trade union committee holds 99% of Huawei's shares as an employee "shareholding vehicle" does not prove that Huawei is an enterprise controlled or even owned by the state. The argument that Huawei is a state-owned enterprise controlled by a labor union is not valid.

Responding to the questions in Balding and Clarke's paper is not the only purpose of this article. The Huawei case is instructive for us to consider the historical legacy of the "shareholding reform" of the last century, the practice of employee shareholding, and the future direction of Chinese corporate law: if we were not so eager to marginalize our own original practices and imitate imaginary single models when introducing Western corporate and shareholding systems, and if instead, we left the room in the (Company) law for different practices and institutional knowledge accumulation, wouldn't Chinese corporate law and the law-based practices of Chinese companies have a more solid foundation?

***

The original Chinese version, accessible at WeChat and iFeng.com, includes a lengthy list of footnotes, which are omitted here, since it’s already too long. They are included in the standalone PDF file of this piece, shared via Google Drive.

Translated by Zichen Wang, founder of Pekingnology, a personal newsletter that does NOT represent the views of anybody else.

Errors may well exist, so suggestions for corrections and feedback are welcome - feel free to reply or send an email to zichenwanghere@gmail.com .