China's Consumption Is Not Nearly as Low as It Appears: CF40 Policy Brief

Leading independent econ thinktank finds the gap between China and developed countries across various consumption sectors is significantly narrower when measured by actual consumption volumes.

There is a broad international consensus among economists, policy analysts, and multilateral institutions that China’s level of household consumption is significantly lower than what would be expected for a country of its economic size and development.

However, a recent policy brief from a leading research institution reveals that the gap between China and developed countries across various consumption sectors is significantly narrower when measured by actual consumption volumes rather than by per capita consumption expenditure.

Founded in 2008, China Finance 40 Forum (CF40) is a leading independent thinktank focused on policy research in macroeconomics and finance. Its core membership consists of 40 leading experts from government, financial institutions and academia around the age of 40. In 2021, the CF40 Institute was established to strengthen CF40’s research capacity. In 2024, the CF40 Institute introduced an original research product, CF40 Research, aimed at providing independent insights into China’s macroeconomy, policy trends, financial market dynamics, and global affairs. CF40 Research currently features English product series including Policy Brief and Commentary.

China's Consumption Is Not Nearly as Low as It Appears

by YU Fei and GUO Kai

YU Fei is a research fellow at the CF40 Institute, focusing on research related to the real estate market and household consumption. She earned her Master's degree in Economics from the Central University of Finance and Economics in 2023.

GUO Kai is Executive President and Senior Fellow of CF40 Institute. Before joining CF40 Institute, Dr. Guo was an economist at the International Monetary Fund in Washington DC and then worked at the People’s Bank of China in various capacities, including in the Monetary Policy Department and the International Department. His main research areas include the Chinese economy and its macroeconomic policies as well as international finance. Dr. Guo is the author of three popular Chinese economics books and multiple academic papers in various English and Chinese journals. Dr. Guo holds a Ph.D. degree in economics from Harvard University.

Abstract: China's consumption issues have long been a focus of attention. Examining consumption rates and per capita consumption expenditure, there is a significant disparity between China and other economies. This paper examines China’s consumption levels by comparing actual consumption volumes. Through a comparison with major economies—including the United States, Japan, Germany, France, and Mexico—it finds that the gap between China and developed countries across various consumption sectors is significantly narrower when measured by actual consumption volumes rather than by per capita consumption expenditure.

In terms of food consumption, China has reached and surpassed the levels of developed countries. Regarding manufactured goods consumption, the actual consumption volume of Chinese people is roughly equivalent to that of countries at similar stages of development. Although it is slightly lower than that of developed countries, the gap is far smaller than what is suggested by consumption expenditure figures. In terms of housing, the average number of residential units and per capita floor area for Chinese residents is not significantly different from that of developed countries. In the realm of service consumption, China's consumption volume and utility in basic education and healthcare services are roughly on par with developed countries, while there is a slight gap in tourism consumption.

We believe that China's per capita consumption level should in fact be higher than Mexico's (approximately $10,000), and should at least reach 40%-50% of the levels of major developed countries such as Japan, Germany, and France. Measured in terms of physical consumption volume, China’s consumption level may be nearly twice as high as that indicated by expenditure data.

After a systematic comparison, we have arrived at four summary observations: First, China’s consumption level is systematically underestimated. Second, this underestimation primarily stems from price advantages and exchange rate deviation. Third, although China’s consumption level is no longer low, there remains considerable potential for further expansion and quality enhancement of consumption. Fourth, actively promoting consumption to achieve a more balanced trade structure will support high-quality domestic economic development and help create a more favorable external environment.

I. Why Compare Actual Consumption Volumes

The issue of insufficient household consumption in China has long been a focus of research and discussion, with many indicators used to measure consumption levels.

First is the ratio of household consumption to GDP, or the consumption rate, which can measure the significance of a country's consumption in the overall economy. From the perspective of consumption rate, China's consumption level is indeed relatively low. In CF40 Policy Brief Policy Options and Priorities for Expanding Consumption in China, authors used flow of funds data to calculate the ratio of household final consumption to GDP, finding that China's consumption rate is at a relatively low level compared to economies at similar development stages. However, consumption rate cannot accurately measure the absolute level of household consumption.

Secondly, by adjusting for exchange rates, the per capita final consumption of different countries can be converted into a common currency unit, allowing for an absolute comparison. In this study, we selected five economies for comparison with China: the United States, Japan, Germany, France, and Mexico. Among these, Mexico’s per capita GDP is relatively close to China’s, making it a representative country at a similar stage of economic development, while the United States, Japan, Germany, and France are developed countries with significantly higher per capita GDP levels.

As shown in Figure 1, the per capita GDP levels of China and Mexico are relatively close, at $12,600 and $13,800 respectively. However, China's per capita household consumption is $4,936, which is only half that of Mexico. This also means that China's consumption rate is far lower than Mexico's, with Mexico's consumption rate at 70.3% in 2023, while China's is at 39.1%.

The absolute value of China's household consumption is also significantly lower than that of developed countries, with per capita household consumption being only 8.8% of the United States, 26.8% of Japan, 18.2% of Germany, and 20.7% of France.

In other words, from the perspective of per capita consumption expenditure, China's consumption level is not only about half that of Mexico but also less than one-third of Japan and less than one-tenth of the United States. China's overall household consumption level is far below that of countries at similar development stages and developed economies.

Finally, there is the absolute value of per capita consumption adjusted for purchasing power parity. Although exchange rate adjustments unify the price units, they do not account for the impact of different price levels across countries. When comparing consumption levels across countries, we often opt for purchasing power parity-adjusted data to avoid the influence of price factors.

The core of purchasing power parity lies in constructing a relative price index: first, collecting price data across various sectors such as clothing, food, housing, and transportation in different countries; then, performing a weighted average according to the weights of a consumption basket, forming a comprehensive price index; and finally dividing the total consumption by this price index to obtain the actual consumption level.

As shown in Figure 2, after adjusting for purchasing power parity, China's per capita GDP is 24,500 international dollars, and per capita consumption is 9,586 international dollars, which are 17.1%, 35.3%, 28.5%, 33.5%, and 59.6% of those in the United States, Japan, Germany, France, and Mexico, respectively. After adjusting for purchasing power parity, the absolute value of China's per capita consumption shows a reduced gap compared to other countries, indicating that the prices of goods and services in China are relatively low. Nevertheless, the absolute value of China's per capita consumption still appears to be significantly lower.

However, the reliability of purchasing power parity-adjusted results is highly dependent on the accuracy of price index estimates. According to the latest data from the World Bank's International Comparison Program (ICP) 2021, China's GDP composite price index stands at 97.9 (with the world average level set at 100).

However, through a comparative analysis of prices in various economic sectors, we find that this data may be somewhat overestimated. For instance, in the apparel and footwear sector, the data shows China's price index at 165.8, which is significantly higher than that of Hong Kong (99.4) and the United States (122.7). This implies that China's clothing and footwear prices are perceived to be 67% higher than those in Hong Kong and 35% higher than those in the United States. Similar overestimation phenomena are evident in several sectors, including food, furniture renovation, and education (refer to Appendix 1). If these prices are indeed overestimated, it would directly lead to an underestimation of actual consumption by Chinese residents.

Therefore, we believe a simpler and more straightforward approach is to directly observe a country's household consumption level from the perspective of physical consumption volumes, examining where the gaps lie between China's household consumption and other economies. Of course, since it is nearly impossible to conduct an exhaustive statistical analysis of all goods across all areas of consumption in every country, we aim to avoid differences caused by consumption habits and supply structures by selecting core categories that account for a large share of the consumption structure and are representative. We will conduct a systematic comparison of these categories, with a particular focus on the utility ultimately derived from each type of consumption.

II. Food Consumption

Food consumption forms the most fundamental aspect of all consumption categories, encompassing grains, vegetables, fruits, meats, eggs, and dairy products. Given the significant differences in dietary and food supply structures among various economies, our analysis of food consumption primarily focuses on the ultimate outcome of food intake, specifically the absorption of energy and nutrients.

We use per capita calorie supply1 as a core indicator to measure the energy acquisition and consumption of a country's residents. As shown in Figure 3, China's per capita calorie supply exhibits a clear upward trend, rising steadily from approximately 1,400 kcal/day in 1961 to 3,453 kcal/day in 2022. Compared to Mexico, which is at a similar stage of development, China's per capita calorie supply surpassed Mexico in 2013. In comparison with developed countries, China exceeded Japan in 2002, and the gap continues to widen, partly due to differences in dietary structures between China and Japan. In 2022, France and Germany had per capita calorie supplies of 3,505 kcal/day and 3,573 kcal/day, respectively, with China having nearly caught up with France and Germany. Meanwhile, the gap between China and the United States has progressively narrowed, with China's per capita calorie supply reaching 90% of that of the United States by 2022.

In terms of nutrient supply, we selected protein supply as a representative measure. The per capita protein supply for Chinese residents also shows a significant upward trend. As illustrated in Figure 4, it increased from 40 grams per day in 1961 to 128.5 grams per day in 2022, representing approximately a threefold growth. It is important to note that after 2010, the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) updated its statistical methods and population data, leading to a certain degree of leap in data for many economies between 2009 and 2010, with China showing the largest increase. From a horizontal perspective, China’ s per capita protein supply surpassed that of Mexico, a country with a similar development level, in 2009, exceeded Japan in 2008, Germany in 2012, and France in 2015. By 2021, China’ s per capita protein intake reached 125.9 grams per day, surpassing the level of the United States. Currently, China’ s protein supply has fully reached and exceeded the average level of developed countries.

In terms of consumption volume, Chinese residents not only surpass countries at similar development stages in food consumption but also reach and exceed the levels of some developed countries. For instance, when calculated based on per capita consumption expenditure adjusted for exchange rates, China's consumption level is less than half of Mexico's and one-third of Japan's. However, it is evident that our actual food consumption volume is not lower than these countries, whether considering calorie supply or protein supply, China exceeds Japan and Mexico. Therefore, it can be said that in terms of food consumption, China's consumption volume is not low and has reached or exceeded the consumption levels of developed countries, with no significant gap.

III. Manufactured Goods Consumption

The variety of manufactured goods is vast, and we have gathered several major categories, covering areas such as apparel and footwear, household appliances, electronics, and automobiles. Some of the consumption data comes from third-party data platforms. While there may be slight discrepancies in the absolute figures, the relative size, magnitude, and trends of the data still offer meaningful reference value.

1. Apparel and Footwear

The actual consumption of apparel and footwear in China shows a certain gap compared to developed economies but is generally comparable to countries at a similar stage of development. The gap calculated based on consumption volume is smaller than the gap calculated based on per capita consumption expenditure.

As illustrated in Figure 5, the annual per capita purchase of apparel in China has remained relatively stable at around 22 items, showing little fluctuation and roughly equivalent to that of Mexico. In 2024, the per capita apparel purchases in Japan, France, Germany, and the United States were 37, 43, 55, and 90 items, respectively—approximately 1.8, 2.1, 2.6, and 4.3 times that of China.

The overall per capita consumption in these countries is 3.7, 4.8, 5.5, and 11.4 times that of China, respectively. Through comparison, it can be observed that, relative to other economies, the gap in per capita apparel purchases among Chinese household is much smaller than the gap in overall consumption.

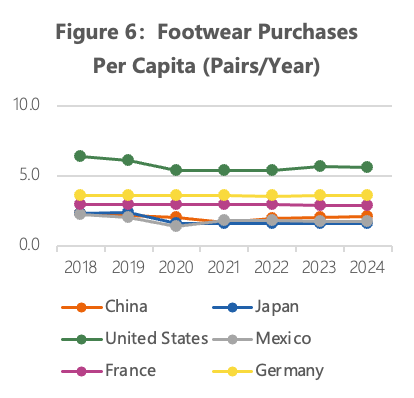

In terms of footwear consumption, according to Statista data, the average number of shoes purchased per capita in China remains stable at around 2 pairs per year, with Japan and Mexico at similar levels. In France and Germany, the average per capita shoe purchase stabilizes at 3 pairs and 3.5 pairs respectively. Although shoe consumption in the United States has declined in recent years, it remains at a relatively high level, with an average of 5.6 pairs per person annually, approximately 2.5 times that of China.

We also referred to data from the "World Footwear Yearbook 2023" for additional insights. According to the Yearbook, China’ s per capita shoe consumption in 2022 was 2.78 pairs, slightly higher than Mexico's 2.45 pairs per person. Japan, France, and Germany have similar consumption levels, around 5 pairs per person, while the United States has the highest per capita shoe consumption at 8 pairs per person.

2. Household Appliances

Overall, China's per capita consumption of household appliances shows an upward trend, with certain categories already at relatively high levels. Although some categories still lag behind other developed economies, the gap measured by consumption volume is significantly smaller than the gap measured by per capita consumption expenditure.

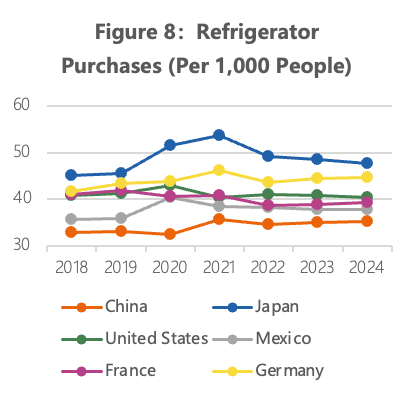

After 2021, the per capita refrigerator purchase in China increased, with an average of 35 units purchased per 1,000 people. This is slightly lower than Mexico's 38 units, France's 39 units, and the United States' 40 units. Germany and Japan have slightly higher per capita refrigerator purchases, at 45 units and 48 units respectively. In contrast to refrigerators, the market scale for freezers is relatively smaller. By 2024, the consumption levels in China, the United States, and Mexico are relatively close, with purchases averaging around 8 units per 1,000 people. Japan and France have similar freezer purchase levels at 11 units per 1,000 people, while Germany is slightly higher at 13 units per 1,000 people.

In recent years, the purchase of washing machines in China has remained at a level of 26 units per thousand people, which is very close to Mexico's 28 units per thousand people, yet below the consumption levels of developed countries. In 2024, washing machine purchases in Japan, the United States, France, and Germany reached 36, 39, 41, and 42 units per 1,000 people respectively—less than twice the level in China.

In terms of air conditioner, China has a purchase volume of 31 units per thousand people, which is significantly lower compared to Japan's 78 units, yet still surpasses other sample economies. In 2024, the United States has a purchase volume of 26 units per thousand people, France 13 units, and Mexico 8 units, all of which fall below China's consumption level.

3. Consumer Electronics

China’s per capita consumption of electronic products is indeed lower than that of other economies and also falls below the consumption levels of countries at similar stages of development. However, even so, the gap in per capita electronic product consumption between China and other countries is smaller than the gap measured by per capita consumption expenditure.

In recent years, the per capita mobile phone purchase volume across various countries has generally shown a downward trend. Mobile phone purchases in China have continuously declined since 282 units per 1,000 people in 2018, with a moderate recovery projected to reach 192 units per 1,000 people by 2024. In 2024, China's mobile phone consumption is slightly lower than that of Germany, France, Japan, and Mexico, but the gap is not significant. The United States has a much higher mobile phone purchase volume per 1,000 people compared to other economies, reaching 388 units per 1,000 people in 2024, which is 1.5 times that of China.

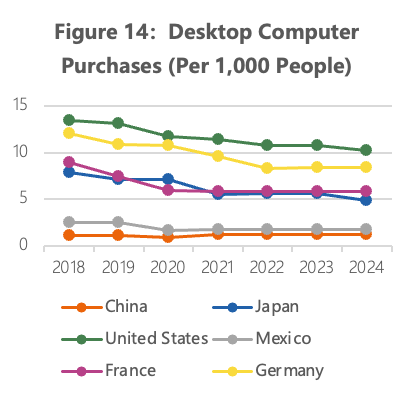

The computer market is predominantly driven by laptop consumption, whereas desktop computer consumption is relatively small and has been declining across various countries in recent years. China's computer consumption is lower than other economies, with a forecasted purchase rate of 10 laptops per 1,000 people in 2024, which is less than Mexico's 15 laptops per 1,000 people. The figure is significantly lower than that of developed economies; in the United States, the predicted laptop consumption for 2024 is 48 units per 1,000 people, which is 4.8 times that of China. In France, the consumption rate is 39 units per 1,000 people, approximately four times China's rate. Japan and Germany both have a consumption rate of 34 units per 1,000 people, which is 3.4 times that of China.

In terms of electronic products such as televisions and tablets, which are more oriented towards leisure and entertainment, China's consumption is relatively low. This may be related to the lifestyle or consumer preferences of Chinese residents. In 2024, China’s TV purchases stood at 34 units per 1,000 people, compared to Mexico’s 52 units—1.5 times that of China; Japan’s 65 units, nearly double China’s; and the United States’ 121 units, almost four times China’s level. For tablets, China’s consumption remains steady at 16 units per 1,000 people, while Mexico records 27 units—1.6 times China’s figure; Japan and the United States also reach approximately twice and four times China’s consumption levels, respectively.

4. Automobile

Due to differences in the classification of passenger vehicles and commercial vehicles between the United States and other countries, we combine these categories to analyze automobile consumption. As illustrated in Figure 17, the volume of automobile purchases in China has shown a continuous upward trend, starting from 18 vehicles per 1,000 people in 2019 and expanding further in recent years, projected to reach 22 vehicles per 1,000 people by 2024. China’s level of automobile consumption is far higher than Mexico’s, nearly double its consumption volume, and the gap with developed economies is steadily narrowing.

The automobile purchase volume in developed economies such as the United States significantly declined during the pandemic. Although there has been some recovery in the past two years, it still does not match the levels of 2019. In 2024, the per 1,000 people automobile purchase volumes in the United States, Germany, Japan, and France are expected to be 48, 38, 36, and 31 vehicles respectively, which are 2.2, 1.7, 1.6, and 1.4 times that of China. In terms of per capita consumption expenditure, these countries reach 11.4, 5.5, 3.7, and 4.8 times that of China. Clearly, the gap between China and these countries in the number of automobile purchased per capita is much smaller than the gap in consumption expenditure per capita.

Overall, China's per capita consumption of manufactured goods is roughly on par with countries at a similar stage of development, only slightly lower than the level in developed countries. However, the actual consumption gap is much smaller than the gap calculated based on per capita consumption expenditure. Compared to major developed countries such as Japan, Germany, and France, China's per capita consumption of household appliances is approximately 60%-70% of these countries' levels, per capita automobile consumption about 50%-60%, per capita apparel and footwear consumption roughly 50%, and electronic product consumption around 40%-50%.

IV. Housing Consumption

Housing consumption can be compared using two indicators: per capita floor area and per capita housing units.

China's official statistical data currently includes per capita floor area only. In the CF40 Policy Brief The Long Tail IV: No Oversupply but Misallocation in Real Estate Market, authors mentioned that according to the 2020 census data, the total urban population in China is 876 million, with a total residential area of 33.96 billion square meters, resulting in a per capita residential floor area of 38.76 square meters per person. The key to estimating the per capita housing units lies in determining the average area per housing unit. We have used transaction data of commercial housing from 30 large and medium-sized cities between 2010 and 2024 for measurement: over 15 years, these cities have cumulatively transacted 2.81 billion square meters of commercial housing, totaling 26.56 million units, thus deriving an average area per unit of 106 square meters. Based on this standard, it can be preliminarily estimated that the per capita housing units in China is 0.365 units.

As illustrated in Figure 18, France's per capita housing units reach as high as 591 units per 1,000 people, which is 1.5 times that of China. The United States has 1.1 times China's per capita housing units, Japan 1.3 times, and the OECD average is 1.2 times China's level. Mexico's per capita housing units stand at 278 units per 1,000 people, which is lower than both China and the OECD average. Viewed in this light, China's per capita housing units are not significantly different from the average level of developed economies, and compared to OECD countries, it is roughly positioned at the lower-middle level.

However, the number of housing units as an indicator is influenced by the average floor area of individual residences and cannot fully reflect the living standards of a country's residents. Therefore, we have collected relevant data from other economies and calculated the per capita floor area for comparison with China. As shown in Figure 19, China's per capita floor area is 38.8 square meters, which is very close to Mexico's 39.6 square meters. Japan, Germany, France, and the United States have per capita floor areas of 45.8, 53.6, 58.8, and 62.9 square meters, respectively, which are 1.2, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 times that of China. If we also consider the residential area in China's rural regions, this gap would further narrow.

In terms of housing ownership and floor area, the housing standards of Chinese household are not low. The gap in per capita housing units and floor area between China and developed countries is relatively small, much less than the disparity calculated based on per capita consumption expenditure. When adjusted for exchange rates, China's consumption level is less than half of Mexico's. However, in terms of residential area and housing units, China is on par with Mexico, and the per capita floor area is approaching that of developed economies like Japan.

V. Service Consumption

Service consumption encompasses a wide range of categories, involving sectors such as accommodation, dining, culture and entertainment, education and training, and healthcare. Unlike tangible goods, service consumption tends to have a lower degree of standardization in terms of quality, with quality assessments being somewhat subjective. For instance, the effectiveness of educational services, the experiential quality of dining and accommodation, and the artistic level of cultural performances all present challenges in establishing uniform quantitative standards. Consequently, in our comparison, we temporarily exclude differences in service quality from consideration and instead conduct a straightforward comparison based on relatively standardized indicators.

1. Education

Consumption in the education sector includes formal education, extracurricular training, and quality education. Here, we select the average expected years of schooling as the core indicator for measuring the baseline level of national education consumption. Expected years of schooling refers to the total years of education that children can expect to receive from primary to higher education, based on current enrollment patterns. As shown in Figure 20, with the universalization of compulsory education and the large-scale expansion of higher education, China’s average expected years of schooling per capita has shown a continuous upward trend, rising significantly from 8.6 years in 1990 to 15.2 years in 2022—an increase of 76.7%. Although the starting point for China's average expected years of schooling was relatively low, its growth rate has been rapid, catching up with Mexico by 2010 and surpassing it by 2019. By 2022, China had essentially caught up with Japan, with less than a one-year gap compared to France and the United States, and less than a two-year gap compared to Germany. Therefore, from the perspective of this quantitative indicator of expected years of schooling, the educational level of Chinese residents is at least not low.

2. Healthcare

Evaluation of healthcare consumption includes numerous indicators, such as the density of medical facilities and the physician ratio, which are input indicators. We use average life expectancy as an outcome-based indicator to measure the actual effectiveness of healthcare consumption across countries. Of course, average life expectancy is not solely influenced by medical standards, but also related to lifestyle, environment, and other factors.

However, it can, to some extent, measure the level of medical services enjoyed by a country's residents. As shown in Figure 21, China's average life expectancy has experienced a long period of stable growth, starting from 53 years in 1965 and reaching 78 years in 2023. China's average life expectancy maintained a similar level to that of Mexico until 2004, after which China continuously improved and gradually widened the gap. In 2020, China surpassed the United States, and the gap with Japan, France, and Germany is constantly narrowing. In terms of final outcomes, the development of China’s healthcare system has achieved remarkable results and compares well with those of developed countries.

3. Entertainment

Entertainment consumption takes various forms, encompassing numerous fields such as tourism, cultural entertainment, and sports leisure. Here, we use tourism consumption as an example to analyze the overall state of entertainment consumption.

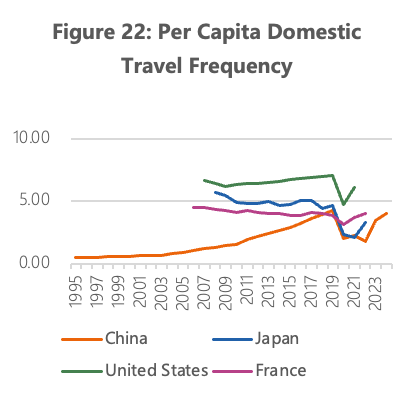

Regarding domestic tourism, the average annual domestic travel frequency per capita in China has consistently increased from approximately 0.5 times in 1995 to a historical peak of 4.2 times in 2019, surpassing France's 3.86 times and closely approaching Japan's level of 4.6 times. Despite a decline due to the impact of the pandemic in 2020-2022, by 2023, the average annual domestic travel frequency per capita in China rapidly rebounded to about 4.0 times, essentially recovering to its previous peak level.

In terms of international tourism, China has also shown a stable growth trend. The annual per capita outbound tourism frequency increased steadily from nearly zero in 1995 to approximately 0.11 times in 2019. Japan's per capita international tourism frequency has remained relatively stable in recent years, at about 0.16 times in 2019, indicating a gradual narrowing of the gap between China and Japan in international tourism.

The per capita international tourism frequency in the United States, Mexico, and France is relatively high, reaching 0.52, 0.66, and 0.73 times respectively in 2019. It is important to note that the frequency of domestic and international travel consumption is closely related to factors such as geographical location, cultural traditions, and lifestyle.

When considering domestic and international tourism together, China's tourism consumption level is relatively close to that of the developed economy of Japan, suggesting that in the realm of tourism and entertainment, China's consumption level may not be considered low.

The domain of service consumption encompasses a wide range of areas and diverse categories, making it challenging to establish a unified standardized measurement system. Therefore, we have selected three representative fields—education, healthcare, and tourism—for comparative analysis. From these three dimensions, the consumption volume and the utility derived from basic education and healthcare services by Chinese residents are generally at the same level as those in developed countries. The travel frequency per capita is slightly behind other countries, but this gap is significantly smaller than the difference calculated based on per capita expenditure.

It is important to emphasize that assessing service consumption should not solely focus on consumption frequency, as service quality and consumer experience are equally significant. For example, the level of quality education beyond basic education, the extent of extracurricular interest development, and satisfaction with the travel experience—all of these consumption utilities are difficult to quantify and compare, yet they are key indicators for measuring the level of service consumption. Here, we mainly use relatively basic utility indicators to measure the level of per capita service consumption. Considering the current stage of development and economic structure, China still needs to focus on improving quality and utility in the field of service consumption.

VI. Summary

Although there is a significant gap between China and developed countries in terms of per capita consumption expenditure, an analysis based on actual consumption volume shows that this gap is much smaller than the one reflected by per capita spending.

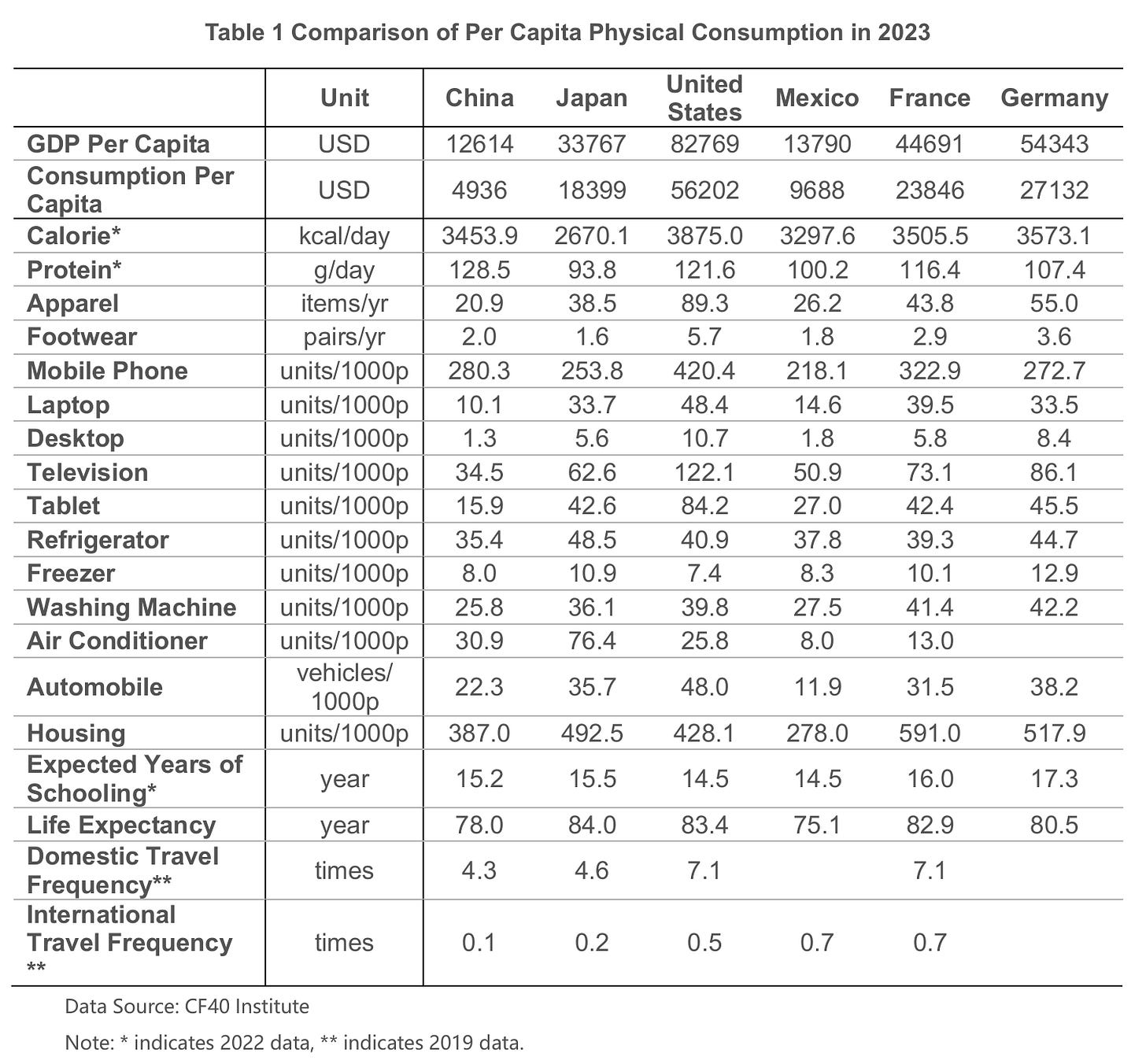

Here, we have outlined the performance of China and major developed economies in various categories of actual consumption volume for the year 2023 (or the latest data available for each indicator). As shown in Table 1.

To provide a more intuitive representation of the consumption gap between China and other economies, we further calculated the relative proportion of China's consumption to other economies, that is, how many times China's consumption equates to that of other economies (Table 2), and conducted comparisons from three dimensions.

First Dimension: Comparison of Absolute Consumption Volume. Red font indicates that the absolute value of this type of consumption in China has surpassed other countries (relative ratio greater than 1). In key areas such as food, mobile phones, certain household appliances, education, and healthcare, China's consumption volume or consumption utility has directly reached or even exceeded that of some developed countries.

Second Dimension: Comparison Based on Per Capita Final Consumption Expenditure. Except for smaller sectors such as desktop computers and international travel, the gap between China’s actual consumption volume and that of developed countries is significantly smaller than the gap in consumption expenditure in other areas.

Third Dimension: Comparison Based on Per Capita GDP. Values highlighted in yellow in Table 2 indicate that the gap between China's physical consumption and that of the respective country is smaller than the gap in per capita GDP. As shown, apart from electronic products, China's actual per capita consumption in comparison with other countries is less than the disparity in per capita GDP.

Taking Japan as an example, China's per capita consumption is only 26.8% of Japan's. However, in terms of per capita absolute quantities, the consumption of calories, protein, shoes, and mobile phones has surpassed that of Japan. The consumption of clothing, televisions, refrigerators, and automobiles is also significantly higher than 30% of Japan's, roughly ranging between 50% and 80%. Expected years of education, life expectancy, and domestic tourism services consumption are approximately at 90% of Japan's level. Only the consumption of laptops and desktop computers is below 30% of Japan's, roughly around 20%, but the gap is not significant. Therefore, from the perspective of physical consumption quantity, 30% clearly exaggerates the consumption gap between China and Japan.

Taking Mexico as an example, China's per capita consumption is only 50% of Mexico's, yet our absolute consumption in terms of calories, protein, mobile phones, air conditioners, cars, and housing has surpassed that of Mexico. The consumption of clothing, laptops, televisions, tablets, and other electronic products, as well as refrigerators and washing machines, significantly exceeds 50% of Mexico's consumption, approximately ranging between 70% and 90%. Only international travel frequency is lower than Mexico, approximately at 20%. Therefore, China's per capita consumption level should be higher than Mexico's, rather than just 50% of Mexico's.

Overall, we believe that China's per capita consumption level should actually be higher than that of Mexico (approximately $10,000), rather than just 50% as indicated by the per capita consumption expenditure. It should also reach at least 40%-50% of the levels of major developed countries such as Japan, Germany, and France, rather than the 20%-30% shown by the expenditure figures. If measured in terms of physical consumption volume, China's consumption level might be about double the current level indicated by expenditure data.

Based on the aforementioned systematic comparison, we can derive four summarizing observations.

First, there is a systematic underestimation of consumption levels in China. The absolute per capita consumption is significantly higher than the level reflected by per capita consumption expenditure adjusted for exchange rates, as well as higher than the per capita consumption level adjusted for purchasing power parity, and even exceeds the consumption level corresponding to China’s current stage of economic development. This systematic underestimation is evident across multiple consumption categories—from food consumption to durable goods, and from basic living needs to discretionary spending—demonstrating that Chinese residents’ actual consumption capacity significantly exceeds the levels shown by traditional international comparison methods.

Second, the reason China’ s consumption level is underestimated lies in prices and exchange rates. From the price perspective, per capita consumption equals consumption volume multiplied by consumption price. Since China's actual consumption volume is not low, this implies a systematic characteristic of relatively low prices for goods and services in China. As the "world's factory" and a populous nation, China leverages a complete industrial chain, economies of scale, and relatively low factor costs to provide goods and services at prices far below the international market level. From the exchange rate perspective, China's higher actual consumption volume reflects the strong real purchasing power of the renminbi; however, this purchasing power advantage is not fully manifested in the exchange rate level. According to the purchasing power parity theory, exchange rates should reflect the relative price levels of goods between two countries, but the current renminbi exchange rate may be undervalued compared to its real purchasing power.

Thirdly, although the consumption level of Chinese residents is no longer low, there is still room for improvement—not only in terms of quantity but also in quality upgrades. From a quantitative perspective, there is still potential for increased per capita consumption in categories such as apparel, electronic products, and household appliances. Current consumption subsidy policies are actively targeting these areas to stimulate consumption potential. However, it is essential to consider the sustainability of subsidy policies to prevent a possible decline in consumption after subsidies are reduced. From a qualitative perspective, there is even greater room for consumption upgrading, particularly in the field of service consumption. Service consumption is characterized by personalization and difficulty in standardization, and China has substantial potential for improvement in service consumption sectors such as education, healthcare, cultural entertainment, and tourism and leisure.

Fourth, the scale of China's trade surplus is not affected by the reassessment of consumption levels mentioned above. Actively boosting consumption to achieve a more balanced trade structure is beneficial for domestic economic development and the improvement of household welfare, as well as for creating a better external environment. The systematic underestimation of consumption levels is fundamentally a statistical issue, and regardless of how we recalculate, the objective reality of China's annual trade surplus of hundreds of billions of dollars will not change as a result.

Therefore, we still need to proactively enhance consumption, transition the economic growth model from excessive reliance on investment and exports to a more balanced model driven by domestic demand, which can also directly improve the living standards and welfare of household. From an international perspective, the expansion of China's consumer market will alleviate global trade imbalances, creating a more stable and friendly external development environment.

Per capita calorie supply refers to the amount of calories available to the household per day. It includes both the actual caloric intake and a small portion lost to waste, and can be roughly regarded as the per capita calorie consumption. Similarly, the per capita protein supply refers to the amount of protein available to household on a daily basis.

This is an excellent study of comparative consumption levels between China and other countries. Rather than do the comparison in financial terms (even adjusted for exchange rate differentials) this study addresses the material measures themselves - calories, square metres, number of units etc. The results suggest that on financial measures China’s household consumption patterns and volumes are chronically underestimated and this further suggests that China’s real GDP has also been significantly under-estimated. It finally says something about relative low prices of goods and services in China. This is a vitally important intervention in a global debate about China’s consumption levels, suggesting strongly that western missives are simply off the mark.

This is the kind of robust analysis that is missing from economic discourse about China. The hyper fixation on financial data clearly misses that actual consumption within China. Keep up the great work.