Chinese companies: subservient CCP tools or autonomous commercial businesses?

Colin Hawes of University of Technology Sydney talked about his new book "The Chinese Corporate Ecosystem" at Australia China Relations Institute.

Colin S. C. Hawes, Associate Professor in the Law Faculty at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and Research Fellow at the Australia China Relations Institute (ACRI) of UTS, recently gave a fascinating talk at the ACRI about his new book The Chinese Corporate Ecosystem published at the Cambridge University Press.

The introduction to the book talk:

Many Australian and international policymakers and commentators have expressed deep concern about the expansion of Chinese corporations overseas. They are especially uneasy about Chinese firms being utilised as tools to serve Chinese Communist Party (CCP) goals.

The Chinese Corporate Ecosystem (Cambridge University Press, 2022) by Dr Colin Hawes, Associate Professor in the Law Faculty at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and a Research Associate at the Australia-China Relations Institute at UTS (UTS: ACRI) makes the case that the influence of the CCP over Chinese business corporations is surprisingly limited, due to the complex and fragmentary structure of the political ecosystem in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Rather than viewing Chinese corporations as subservient tools of a CCP-led authoritarian hierarchy, the book argues, their capacity to act as autonomous agents within this fractured corporate-political ecosystem – that is, pursuing their own commercial interests in the PRC and overseas in ways that regularly subvert Communist Party policies – should be recognized.

Thanks to the generous authorization of the Australia China Relations Institute (ACRI) of UTS and Associate Professor Colin Hawes, I’m happy to share part of his book talk and slides. All emphasis is mine. - Zichen

Now, we tend to think of it as a pyramid with very tight control from the top with the party, the Communist Party. Xi Jinping is the president, and a small number of Standing Committee members at the top, and they control the pyramid very tightly. And it expands out through these different committees at different levels right down to the rank-and-file party members. And there’s about 96 million of them registered as Communist Party members.

And then the Communist Party itself, we see them as controlling all of these government institutions at various different levels. And social institutions like universities, colleges, public bodies, and even private corporations, they often have a Communist Party branch within them. So, it looks like the Communist Party is controlling everything in China either directly or indirectly

But in fact, there’s a lot of forces that prevent that kind of control and they’ve become very powerful over the last few decades. And they include corruption and guanxi, which is personal relationship networks in China, and self-interest of all sorts of people within this system. And that subverts the ability of the Communist Party to actually control the whole society or even itself as a Party.

So, well-informed political-science experts have already talked about this a lot over the last few decades. They’ve said that the Chinese government or party is fragmented or decentralised in its authoritarianism.

There’s a lot of local experimentation and competing vested interests among government officials and ministries’ departments in the government. Bureaucratic bargaining between policy entrepreneurs and a dynamically-fluid braided stream of continually-interacting ad-hoc and contingent contradictions. It doesn’t sound like a very tightly centrally-controlled system. And there’s constant tension between the centrifugal forces trying to break China apart and centripetal forces, the Communist Party trying to keep things together.

So even though this has been identified by many political science experts, it hasn’t really come through into when people talk about Chinese corporations.

So, my book is about what I call the corporate ecosystem or corporate-political ecosystem. And I found in my research that it’s equally a chaotic kind of maelstrom of interests. Complex corporate-political networks which frequently subvert the government and the party at every level. And it’s uncentered and meandering, non-hierarchical, full of horizontal multiplicities which cannot be subsumed within a unified structure. So, it’s more like this diagram on the book cover, which is the yin-yang diagram.

Which you have to imagine this swirling around in a constant flux of interests, competing interests, and people working together in little groups. And often they subvert the central control of the government, and many of those are corporations.

So, I’m trying to provide more accurate information to Australian and international policy makers through this account, and dispel some of the more lurid myths about the China threat.

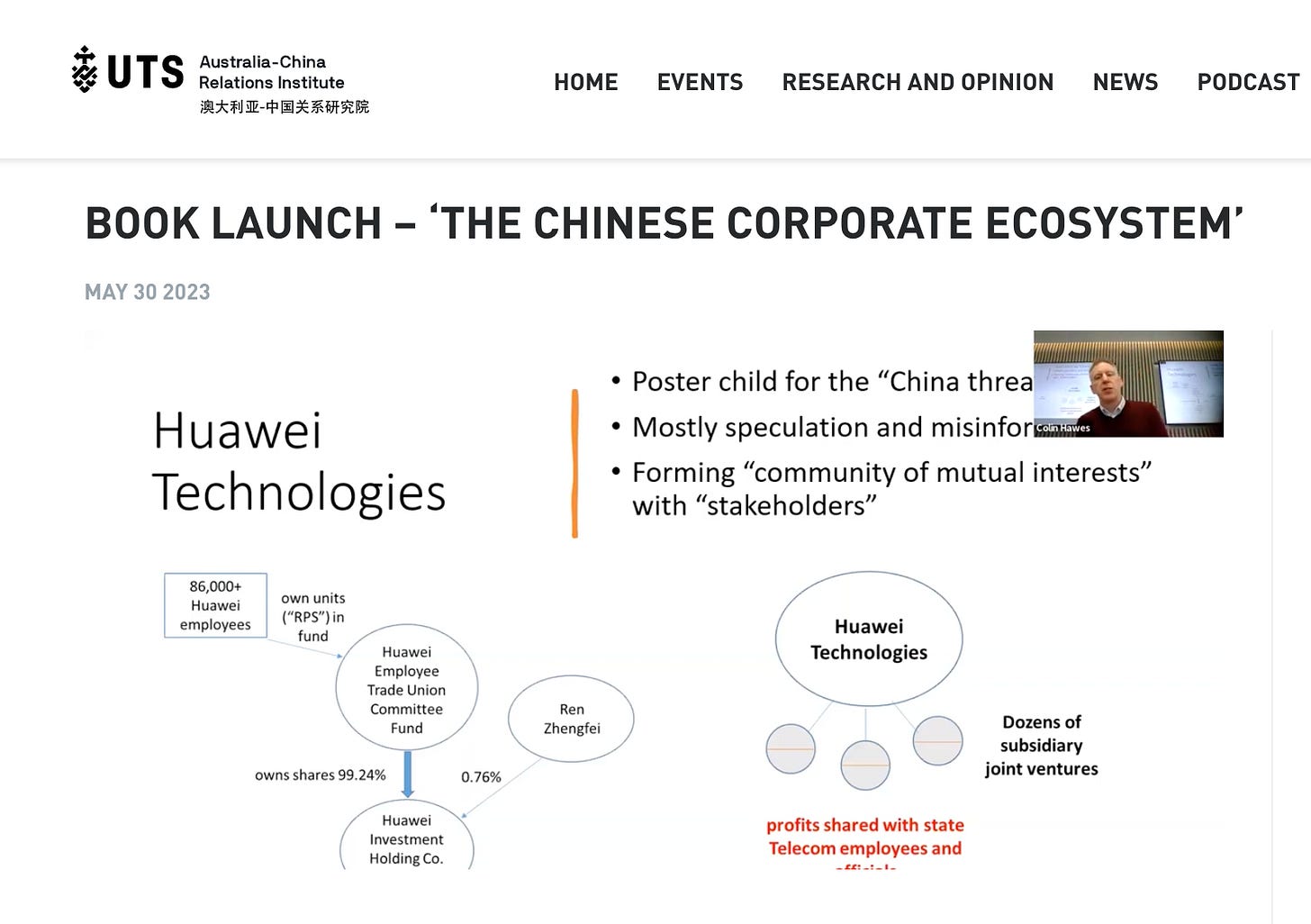

To put that into a context with a private corporation in China, Huawei Technologies, this is a very successful Chinese company, a privately-owned company.

Which over the years is often seen as a poster child for the China threat, but that’s mostly a speculation, a misinformation. That’s something I talk about a lot in my chapter on Huawei in the book. But they became successful by forming this community of mutual interests with their stakeholders. And so, on the one hand, they incentivise their employees through allowing them to get shares in the company. So most of Huawei employees in China own shares in Huawei through an investment fund, and they get profits when Huawei gets profits. And a lot of them became quite wealthy through this, and it gave them an incentive to work very efficiently and to make sure that Huawei was profitable.

Secondly, they used a similar method to get their customers involved in sharing the profits. So, the customers, because they produce telecom hardware and internet equipment that makes the internet work, basically, their main customers were the state telecom firms in China initially. So, they set up these joint-venture subsidiaries, which shared profits with the employees and officials of those telecom firms. Because their salaries were not very high, they were very happy to do this, because then they could get benefits from buying Huawei’s products. So, these state firms had incentive to buy Huawei’s products because the employees and officials would share in the profits as well. And it’s a long-term thing, because the technology is constantly improving and it needs to be upgraded. So, you get 2G up to 4G and 5G, et cetera. And so, there’s a constant profitable market there.

Huawei was also, I guess, benefited from the fact that you had a society where you had very few telephone users, very few mobile phones, and no internet in the 1990s. And then suddenly over a period about 10- to-15 years, you get up to about a billion people using mobile phones and the internet. So, they needed all these networks to be built, the hardware behind the internet and mobile phones. And so, there were huge opportunities available for private companies to fill in the gaps. And once they became big enough, and then they were actually so big, they were the biggest taxpayer in China. And so, they were benefiting the government in that way, and also through the government not having to rely so much on foreign technology firms to build their internet networks.

So that’s forming a community of mutual interest. And these joint ventures were actually legal at the time, so I won’t go into why that was, but it was not an illegal kind of corrupt network. It was done openly.

The other company I look at a lot in the book is Alibaba and Ant Group, another private corporation, they’re related companies in a group. And Alibaba basically does e-commerce where millions of independent merchants can use their sites like Taobao and Tmall to sell products online. And when they first started out, there was no online-payment system in China, so they set one up themself and they called it Alipay. And that solved a huge problem for people wanting to buy and sell online, that they could do it all as an online payment instead of going through a bank in the high street.

So, they managed to attract huge numbers of customers, building up to hundreds of millions of customers over a period of about 10 years. And they realised that they could use the data that they had of all these customers and merchants using their websites. They could collect this data and find out what the financial needs were of these people, how much money they had, and whether they wanted to invest money, and their credit ratings. So, they collected all that data through this Ant Group, and then recommended millions of customers to state-owned banks, insurance firms, and finance firms who would then sell financial products. So, they were doing the job of vetting the clients, if you like, or customers for the state enterprises who are providing the finance.

And it filled a gap, because most of these customers probably didn’t have any much investments before, and suddenly they were able to buy these financial products and make a bit of profit out of that. So, you can see there they’re filling a gap in the market. They’re bringing in the state-owned firms who also benefit. And some of those finance firms, the big ones are run by princelings who are like the children of senior Communist Party officials. And so, they’re indirectly benefiting some of these Communist Party officials as well. It’s like an ecosystem, a mutualistic ecosystem where everybody basically benefits. I’m not saying that they’re perfect, they had some problems as well, but I don’t really have time to go into that.

So, you can see those groups like Huawei, Alibaba, and also the Shenzhen housing market, they’re on the intersection between the private and the state. But they’re using the state to benefit themself and their own commercial interests, while at the same time trying to benefit the Chinese economy. And so, the government basically is happy for them to do that.

So, to finish off, I want to just remind you about the difference between the surface and the reality. The reality often is that individuals or individual corporations are acting in their own interests, even government officials often acting in their own interests. So it may be that corporations have government links, but you have to look at how those links are being used. It’s not just a simple case of government controlling corporations. Often there’s self-interest or family interests of government officials, which they dress up as national interest, but actually they’re just benefiting themself and not so much the country. And what looks like Communist Party control is often corporate capture of officials by these corporations.

So, in terms of the relevance for Australia, we have to realise that the central Communist Party is much weaker than it appears on the surface. They’re engaged in this futile struggle to keep control, and sometimes seem to be losing that struggle with all these corruption cases. We shouldn’t always blame the central government, or Beijing as it’s often called, for when we see what looks like Chinese actors doing things we don’t like. We need to pay more attention to the individual, local corporate self-interests and see how they are influencing the way that these people behave.

And we should also modify our views of Chinese corporations overseas. Because companies like Huawei and TikTok when they come overseas, they are really acting for commercial interests. And so, if we understand that, it might help to reduce international tensions. Because we’re not looking at every single Chinese corporation as if it’s an agent of the Chinese Communist Party trying to subvert Western society.

Question: ‘What is your view of state-owned enterprises operating in Australia in the resources sector such as iron ore? How close are they to Communist Party control and influence?’

Answer: So, in my chapter on state-owned enterprises, I basically show that a lot of those state-owned enterprises have now become more like commercial firms and looking to make a profit. And it’s quite difficult for the Communist Party to control and influence them, especially when they go overseas. And that’s resulted in some countries, in developing countries overseas, in quite a bit of corruption involving state-owned enterprises.

In Australia there’s not a problem with that, but I think you really need to view those state-owned enterprises as economic bodies. At the same time, their senior executives in China, the parent companies, they are Communist Party officials mostly, and they are counted as government bureaucrats. They have a certain ranking on the official system, and they’re vetted by the Party’s organisation department before they’re appointed. So, there’s definitely an overlap, if you like, between the government and these firms at the highest levels in their headquarters in China. And so they’re going to be at the same time trying to follow party policies more generally like: ‘You can invest in this country. We want you to do this kind of investment overseas.’ They’re going to do that, but it’s not like the Communist Party is interfering in the management of those firms as they’re operating overseas.

They tend to just follow the local laws, whether they’re good or bad laws, and to adapt to the local commercial environment. So, I don’t think the idea that a state-owned enterprise is investing in Australian iron-ore firms or mining companies here, it doesn’t really necessarily mean that the Chinese Communist Party is trying to undermine Australia in some way. They just need the resources.

The full talk in on YouTube

And buy the book

Wasn't Alibaba just broken up? This guy has no idea what he's talking about. He lists no specific examples. He basically just described how western governments work lol

After doing a fine job of explaining the SOE myth, it's disappointing to see Colin Hawes saying stuff like this: "the Communist Party is much weaker than it appears on the surface. They’re engaged in this futile struggle to keep control, and sometimes seem to be losing that struggle with all these corruption cases".

The Communist Party in no way resembles Western command-and-control parties in power.

The CPC's mission is to deliver the 2500-year-old Chinese dream of a dàtóng society by leading them to it through their example and self-sacrifice.

To help make this real, members contribute $1 billion in annual dues and billions of volunteer hours. In an emergency, their lives will be sacrificed first, as they were in Wuhan, where almost all staff deaths were Party members. Same with floods and famines and everything else.

They're not into power in the sense we are.