The Ambassador's Speech: How Tony Blair's spin doctor and others trained Fu Ying

Then Chinese ambassador to the UK's transformative journey of rigorous training to improve engagements with foreign media via British PR companies.

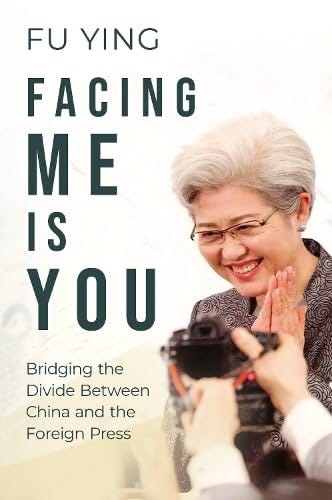

Previously Vice Foreign Minister of China and the ambassador to the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Philippines, Fu Ying was one of the best performers for the People’s Republic of China on the world stage. Five years after its original release, Ambassador Fu's memoir, 我的对面是你,新闻发布会背后的故事, is now available in a fresh English edition titled Facing Me Is You: Bridging the Divide Between China and the Foreign Press by ACA Publishing in Britain since November 24.

Embark on an intriguing journey of discovery into how high-level Chinese party and government officials engage with the media. Packed with anecdotes, no detail is too small to escape the author’s notice, from dressing to impress to addressing North Korea’s nuclear aspirations, disputed islands in the South China Sea and UK demonstrations against the Beijing Olympics.

This book lifts the veil on the behind-the-scenes dynamics of this hitherto opaque world of high-level PRC press conferences. Join Fu Ying at the National People’s Congresses as she adroitly prepares for and navigates tough questions, addresses sensitive issues, and tactfully and cheerfully counters perceived biases.

Travel with her to the UK where, as PRC ambassador, she works to bridge cultural divides and challenge misconceptions about China while simultaneously embracing aspects of UK press culture she can learn from, such as world-class training on how to handle the media.

The following article is an excerpt from Section III: Stories Outside the News Conference, authorized by ACA Publishing. It begins with Fu's arrival in the UK and provides a comprehensive account of her dedicated endeavors in public relations training.

Get Fu Ying’s Facing Me Is You: Bridging the Divide Between China and the Foreign Press from Amazon!

The Chinese original 我的对面是你,新闻发布会背后的故事

“PROGRESSING FANTASTICALLY YET COMMUNICATING BADLY”

While negative public opinion related to the "3·14" riots was still haunting us, the Beijing 2008 Summer Olympics international torch relay was officially kicked off on 24 March and was set to reach London on 5 April. It was a great event in China-UK relations, so several British media outlets sought to interview me. They provided the outlines of issues they wanted to discuss, mainly about the Beijing Olympics and the recent unrest in Lhasa. I thought taking interviews would be a good way for me to directly convey views and information about China to the British people.

The British people enjoy reading and have a habit of following news and current affairs. As a nation of over 60 million people, the number of newspapers, magazines, books, TV and radio programmes, and audio/video products the country has is higher than the world average. Let alone the great influence they have on people's daily life. As the modern media industry originated in the UK, the British media not only influence their own people and people in the Western world, but also the wider international community. The Times, the Financial Times, the Guardian, The Sun, the BBC, etc. have established an international reputation over the years and have wide viewership at home and aboard.

British journalists are professional and sharp. They claim to be standing on behalf of the people to challenge the government and the policies. To deal with the media, the government needs to constantly improve its capabilities and skills. As a result, the two formed into a competing and yet inseparable interdependent relationship. This complicated relationship has also cultivated an increasingly specialised public relations (PR) consultancy and training services sector.

I was introduced to David Hill, who had been a spin doctor for former Prime Minister Tony Blair. We met to or three times and I wanted to learn about the UK's media environment, the characteristics of its local media, and how to deal with them. I noticed that he placed special emphasis on professional training and suggested that to successfully interact with the media, I needed to learn the skills and conduct targeted exercises before each interview. Mr Hill cited his personal experience as a consultant to UK dignitaries. For example, if an important statesman is about to give a five-minute interview, he would spend at least 25 minutes drilling over the few key questions. Hill would challenge the statesman from a variety of angles to prepare him for difficult questions and train him to stick to his original position, thus enabling him to articulate his views and prepare information successfully. After the challenging exercises, the interviewee could handle any tricky questions with ease. Mr Hill told me: "The media may ask anything and you need to be well prepared. The key thing to stick to is: What is your message?"

I benefited a lot from the conversation and realised that I must receive professional training. Through my exchanges with other countries' ambassadors, I discovered that they also attached importance to professional training and preparation when taking media interviews. So my embassy started doing research and considering which specialist agency to reach out to for training assistance.

British PR companies provide highly professional services. Once a contract is made, they start researching and analysing the relevant media reports and commentaries, and developing customised plans to serve clients' specific requirements. However, just like lawyers, PR consulting companies are expensive and the quoted price of Mr Hill's company was beyond the embassy's budgetary constraints. I had to give up on this idea.

A friend introduced me to a smaller communication risk company, and I became friends with its Egyptian-British owners Mr Sameh El-Shahat and his younger sister Ms Samah El-Shahat, who used to be a journalist. Through their father, who had once met Premier Zhou Enlai, the El-Shahats cherished friendly feelings towards China. We hit it off immediately. Speaking of China's international image, Sameh said: "We have never seen a country like yours which has progressed fantastically but communicated badly." Their remarks touched me because it showed that they were aware of the difficulties and challenges facing the embassy. So I decided to use part of the granted special funds allocated for the embassy's olympics-related activities for their special training. They often worked long hours with me, much more than we had paid for, and did not seem bothered when many other embassy staff attended their courses.

The El-Shahats and their team devoted their time to trying to understand Chinese culture, ideas and values. Furthermore, the lamily background made it easier for them to identify with developing countries like China and China's view. They held that the Chinese people should make an effort to share with the word their ideas and values so that people in the UK and other countries may relate to and accept them. Only in this way can we foster respect for China's image, spread China's story and gain more trust from the international community. They also argued that as China grows stronger, insufficient knowledge and a lack of understanding of Chinese ideology and values will only result in the international community developing a greater sense of being threatened by, and hostility towards, China.

I agreed and acknowledged that we, the Chinese, must improve our communication skills and powers of persuasion in order to deal with Western society which had limited knowledge of China and the Western media that has deep-rooted bias against China. As a diplomat, I have been posted overseas for years, so I am keenly aware of how rarely the voice of the Chinese people can be heard in the Western world as well as in the wider international community. We often lack representation at critical moments and on vital issues. Therefore, we need to develop awareness when dealing with the media and enhance our ability to communicate effectively. As the saying goes: "He who sups with the devil should have a long spoon." When dealing with tough opponents, especially if you cannot change the rules, it is important to understand how they conduct themselves and what their objectives are, then draw on their strengths to get your points across. Only in this way can we leverage local communication channels better and convey China's messages, explain the ideas of the Chinese people and tell our story.

STRICT TEACHERS

The El-Shahats were strict teachers. They were very chatty and cheerful when we had tea together, but once the class began, they would tell me that they were journalists now and not friends any more. The first lesson was an interview simulation. They raised a string of questions, which we normally considered "sensitive", in an "unfriendly manner", relentlessly questioning China's political system and its domestic and foreign policies. For me, these were the routine questions when facing Western media; I effortlessly and eloquently refuted all those critical questions. After the simulation, I would join them to watch and analyse the video footage. They asked me to carefully observe my own image on the TV screen. When a tough question was brought up, I appeared extremely serious with my facial muscles contracting. My expression was amplified on the television screen, which further intensified the atmosphere.

They told me, the general public who would be watching would find me lacking in composure and self-confidence as if I had something to hide. People would therefore find it hard to trust me. Samah shared her experience with me and said some journalists would deliberately provoke their interviewees in order to catch them off guard. Normally, the calmer the interviewees are, the easier it is for the audience to focus on the messages they are trying to convey. She suggested: "When taking a question from a journalist, try to refrain from appearing defensive. If a journalist labels you as 'blah blah...' and you try hard to deny the labels, you fall into the trap of self-justification." Instead, a more effective method is to illustrate who vou are and disprove the labels by using solid facts.

The suggestions were very helpful. Why do we receive interviews and face the media? We do so to communicate our information and views to the public. If an interview is likened to a game, the journalist challenging you with questions is your opponent. But the objective of the game may not necessarily be to outperform one another but to win over the public behind the camera. The media is a bridge and a medium of communication. If you do not trust the media, you might as well give up speaking to it altogether. However, once you decide to accept a media interview, you must concentrate on the public who stand behind the media and focus on convincing the public rather than quarrelling with the journalists.

The first step of the professional training was to learn how to face journalists in a relaxed manner and confidently communicate with the target audience, the public. I could tell from watching the footage that I looked more amicable and trustworthy when I smiled as I answered the questions. This rule is actually applicable in normal interpersonal relations.

The second lesson of the professional training was on linguistic expressions, namely, designing the key points of answers and responding to questions convincingly. The point is how to stay away from the routine of "I'm right, so I'm right." The Western public has little background knowledge of China, as not many have access to such information. For instance, a truck driver or a housewife in the UK learns about what is happening in the world by watching television, listening to the radio, going to the pub or talking to friends. But the television programs rarely present first-hand information about China. For me, communicating naturally with the British public was not an easy job both in terms of technical skill and the art of expression. Sometimes, telling a story is more effective than expressing an argument. One's views can be better understood and accepted when using expressions or metaphors the listeners are familiar with.

When I started to discuss issues about China with the El-Shahats that were most frequently mentioned by Western media, I took out a thick book of "white paper" containing talking points covering a wide variety of issues. As I went through it with them, some of the answers were convincing and they agreed with the argument. But, from time to time, they disagreed. They would point out flaws in the reasoning and discuss with me how to better express the points. It was an exhausting and gruelling process. Some of the sentences sounded quite OK to me, but Same would say: "You've lost me." Having listened to my explanations, he would comment that although the wording sounded nice, the meaning was elusive in English. The essential messages became obscure when a lot of adjectives or slogans were used. He suggested that I should use real-life stories and cases to illustrate my points. We discussed the connotations of some concepts and reorganised the sentences. We sometimes would ponder on a specific verb or adjective over and over again.

The training was thorough and strict, including paying attention to some details, such as how to set the tone, make a pause and use gestures. For example, when I spoke, the harsher my words were, the slower my tone should be. That also corresponded to a traditional Chinese saying: "It does not require a loud voice to speak the truth" In addition, while emphasising a point, I was supposed to pause for a moment to draw the audience's attention and allow it to resonate with them. But to pause too often was not good, as it would disrupt the flow of the speech. I was also told to use a few gestures; otherwise, I would look stiff. The appropriate use of gestures would make me sound natural and compelling. My expressions and tones also mattered in front of the camera, so I was asked to adjust myself according to the context of the question. Television interviews are the art of watching and listening and thus an art of expression. In an interview, even when you are specific about the messages and policies you want to convey, whether you are successful or not depends also on the expressive force of your language.

We stuck to the schedule conducting interview simulations, watching video replays, making corrections, engaging in discussions and doing exercises. When my schedule permitted, I would even spend an entire day practicing and discussing with my colleagues what we had learnt. Little by little, I made progress. The intensive training helped me to see my own weaknesses and pushed me to improve quickly. For example, it taught me to keep a cool head under pressure and be better prepared as well as how to flexibly respond to familiar or unfamiliar topics. My performance improved and I was able to deal with and even refute a variety of questions. Same smiled and commented: "Now, you are able to take the initiative and challenge me, instead of passively responding to my challenges." I also came to master some useful techniques like how to use humour and self-mockery, how to present the facts and reason things out, and how to disprove the journalists at the most appropriate time to gain the upper hand.

The El-Shahats led a professional team. Before I took an interview with a media outlet, they would go through its recent reporting on China as well as recent coverage by other media outlets and commentators on the same issues. They would also research for background information on the interviewer and their previous stance. From this massive amount of information, they compiled a condensed summary of about 20 pages of key information, which formed the groundwork for a response plan. With such thorough preparation, the possibility of me running into unexpected questions during the interview was significantly reduced, and there was less probability of failure or me being put on the back foot.

With the help of professional consultants and training, I developed a better understanding of how the British media operated and mastered some techniques for dealing with them. In an information era, the success of public diplomacy depends on not only whether you have a good story to tell, but also your ability to tell it well. Those who do a better job at it have a greater chance of success. It is certainly a formidable task to influence and change the West's prejudice against China. Ultimately, it will be the concrete achievements of China's development that will convince the rest of the world. Nevertheless, by improving our professional skills and successfully conveying China's views and messages via the Western media, we may be able to influence the public on some specific issues. If we continue with this endeavour, over time, we will be able to make a difference.

Fu Ying's story continues with her maiden appearance on BBC Breakfast, March 28, 2008. Find out more about Fu's encounter with Western media in Facing Me Is You: Bridging the Divide Between China and the Foreign Press.

Get Fu Ying’s Facing Me Is You: Bridging the Divide Between China and the Foreign Press from Amazon!

More from ACA Publishing on Pekingnology

I admire Ambassador Fuying. Must read her memoirs!