Wu Xinbo: Golden Memories of China–U.S. Exchanges

Fudan scholar’s memoir of meetings with American presidents, scholars, friends, and mentors shows how human contact shaped U.S.–China ties.

At a time when talk of U.S.–China relations tends to be cast in the language of rivalry and distrust, it is easy to forget the decades of human encounters that helped steady the relationship. Wu Xinbo, Professor and Dean of the Institute of International Studies and Director of the Centre for American Studies at Fudan University, offers a rare reminder. In a personal essay marking the Centre’s 40th anniversary, he recalls meetings with American presidents, senators, and scholars—Bill Clinton likening Anhui to his Arkansas roots; Joe Biden warning Taiwan’s leaders against miscalculation; Barack Obama lingering to shake hands with students; Henry Kissinger’s pithy reflections; Jimmy Carter’s delighted retelling of Deng Xiaoping’s offer to send students to America.

Published in Shiji, a journal jointly run by the China Central Institute of Culture and History and Shanghai Research Institute of Culture and History, and also on the WeChat blog of the Centre for American Studies, Wu’s piece is as much memoir as institutional history. At a time when the relationship feels brittle, such memories carry unusual weight.

Wu Xinbo agreed to but didn’t review the translation before publication.

吴心伯:年华似水 记忆如金——纪念复旦大学美国研究中心四十华诞

Wu Xinbo: Lost Time and Gilded Memories — In Honour of the 40th Anniversary of the Centre for American Studies, Fudan University

In 2025, the Centre for American Studies at Fudan University celebrated its 40th anniversary. Since I joined the Centre in 1992, over three decades have passed. During these thirty years, the Centre has evolved from its pioneering beginnings into a renowned academic hub for American studies, respected both domestically and internationally. Personally, I have grown from a freshly graduated PhD into a key faculty member at Fudan University. Looking back on these years, vivid scenes return in sequence, each bright episode like a golden bead on a single thread, casting a warm light across the span of time.

The Encouragement and Backing of My Forerunners

I graduated from Fudan University’s Department of History in January 1992, supervised by Professor Wang Xi, the founding deputy director of Fudan’s Centre for American Studies. Professor Wang had hoped to place me in the history department as a lecturer, but when that proved unworkable, he recommended me to the Centre. His recommendation was endorsed by the Centre’s director, Professor Xie Xide—by then retired from the university presidency—and by Mr Lu Yimin, director of the University’s External Affairs Office.

Unfortunately, just a few months earlier, the Centre had already hired a young researcher, and the university’s Personnel Office was reluctant to authorise another appointment so soon. Thanks to Professor Wang’s persistence, supported by Professor Xie and Professor Zong Youheng, then the university’s deputy party secretary in charge of personnel, the approval was ultimately granted.

Before I formally took up the post, Professor Wang invited me to his home. He sketched the Centre’s work, lingered on the details that would demand particular care, and, with quiet gravity, left me a charge: “I assured President Xie that you are truly outstanding. You must live up to that expectation.”

More than thirty years have passed, but I have never forgotten those words.

Before I took up the post, I had never studied in the United States. For a researcher in American studies, that was a gap I needed to close quickly through firsthand academic work. Professor Wang Xi never lost sight of this. With the support of Mr Lu Yimin, I was selected as a visiting scholar through the Program for International Studies in Asia (PISA). In January 1994, I set off for a ten-month research stay at The George Washington University.

On the day before my departure, Shanghai lay cold and clear after fresh snow. President Xie Xide came to the Centre and gathered everyone. “Wu Xinbo leaves for America tomorrow,” she said. “We wish him every success and look forward to welcoming him back in a year.” The Centre had previously sent several young scholars abroad; many had not returned. Her words were, in essence, a gentle reminder to finish my visit on schedule and come home to serve the Centre. Such was the care she took, and such was the trust she placed in me.

Before I went abroad, Professor Wang Xi invited me to his home and offered practical counsel for study and life in the United States. He noted, for instance, that American winters are warmed by central heating—no need to pack heavy coats; better to bring extra shirts. He also wrote to my host, Professor Harry Harding, asking that he extend guidance and support.

One matter he stressed in particular was the publication of my doctoral dissertation, Dollar Diplomacy and Major Powers in China (1909–1913). Because I had lacked access to U.S. archives while writing it, he urged me to use my time there to consult original materials at the Library of Congress and the National Archives, then revise the manuscript for publication. I followed his instructions closely, spending two months buried in those collections. After expanding and refining the work, it was published in 1997 as the sixteenth volume in the Studies on Sino–American Relations series, edited by Professor Wang, my first academic monograph.

In July 1997, to coincide with President Jiang Zemin’s visit to the United States, I worked with the Institute for National Strategic Studies at the U.S. National Defence University to host a “China-U.S. Track II Dialogue” at Fudan’s Centre for American Studies. The aim was to explore in depth how to improve and develop bilateral relations. Leading scholars from both sides, among them Wang Jisi, Zhang Yunling, and Harry Harding, took part.

It was the first international conference I had ever organised, and the preparations were anything but simple. I was fortunate to have the unwavering backing of President Xie Xide, then serving as the Centre’s director. She not only attended the dialogue in its entirety but also hosted the welcome dinner. My recollection is that it was uncommon for her to remain for a full Centre event; typically, she would deliver opening remarks, join the group photo, and depart. Her presence throughout signalled both the importance she attached to the subject and her personal support for me.

Following the conference, at the arrangement of Zhou Mingwei, then director of the Shanghai Foreign Affairs Office, former Mayor of Shanghai Wang Daohan received the American participants for a substantive exchange on China-U.S. relations. The meeting left a strong impression. Harry Harding called it the best symposium on China-U.S. relations he had attended in China over the past 20 years. That success would have been unimaginable without President Xie’s steady support.

Witnessing Major Visits

The Centre has long been not only a leading hub for American studies, but also a vital window onto engagement with the United States. Over more than three decades there, I have taken part in or chaired numerous dialogues with senior U.S. officials, several of which left a lasting mark.

The first came during President Bill Clinton’s 1998 visit to China. This was a return trip after President Jiang Zemin’s journey to the United States the previous year, and the first visit to China by an American president since the end of the Cold War. One of Washington’s aims was to show the American public a China in rapid transformation. In Shanghai, the U.S. delegation arranged a roundtable led by President Clinton and the First Lady under the theme “Looking toward China in the 21st Century,” inviting about ten representatives from the city’s legal, educational, cultural, and religious communities. Professor Xie Xide, then the Centre’s director, and I were among them.

Before the forum, Zhou Mingwei, then director of the Shanghai Foreign Affairs Office, convened a briefing for the participants. As we were leaving, he asked me to stay behind. As the only scholar of China-U.S. relations in the group, he said, I should remain policy-sensitive and respond with care to the moment.

The roundtable was held on the morning of June 30 in the main hall on the ground floor of the Shanghai Library. Alongside the invited representatives from Shanghai, the full U.S. delegation and their Chinese entourage were present. Journalists covering the visit lined the corridor above, looking down on the proceedings. The discussion took place in a semi-open setting, and the tone throughout was relaxed.

After the roundtable began, President Clinton first engaged with representatives from the city’s legal, educational, cultural, and religious communities, with First Lady Hillary Clinton actively joining the discussion. I was the last to be called upon. Just before he turned to me, I noticed an interesting detail: National Security Advisor Sandy Berger, seated at Clinton’s side, quietly slipped him a note. Clinton read it, glanced in my direction, and then began his questions.

He opened with a personal one: “Professor Wu, I come from Arkansas in the United States. From your background, I see you are from China’s Arkansas—Anhui Province, and then you entered, and now teach at, one of China’s best universities. How do you view such a journey?” I understood that his question was designed to highlight for the American public the transformations China’s reform and opening up had brought. I spoke briefly about my own experience: how a child from a poor mountainous village could, through the national college entrance examination and with the support of a state scholarship, enter Fudan University, complete his studies, and return as a member of its faculty. I emphasised that today’s China is not only experiencing rapid economic growth but also far greater social mobility and expanding opportunities for personal advancement.

He then shifted the conversation to China–U.S. relations, asking for my views on recent developments and my outlook for the future. I spoke about the setbacks and the progress in bilateral ties in recent years, emphasising that the way the United States handles the Taiwan issue is of critical importance. President Clinton agreed with my assessment and stated that the United States does not support independence for Taiwan, two Chinas, or one Taiwan–one China, and does not believe Taiwan should be a member of any organisation for which statehood is a requirement. His remarks drew considerable attention from both Chinese and international media and were widely seen as a major—indeed, even historic—policy declaration.

[Yuxuan’s note: The official Shanghai Library transcript differs from Professor Wu’s recollection. It shows President Clinton first sought Wu’s assessment of China-U.S. relations and reiterated the U.S. Taiwan policy before turning to a personal question.]

Later, during a visit to Washington, I learned that President Clinton had decided en route from Beijing to Shanghai to reiterate the Taiwan policy publicly. He had already given similar assurances to the Chinese side, in writing and orally, but Beijing sought a formal public declaration during the trip—its foremost objective.

Clinton made no such declaration in Xi’an or Beijing. Only at the Shanghai Library roundtable did he publicly affirm that the United States does not support Taiwan independence, two Chinas, or one China–one Taiwan, and does not support Taiwan’s membership in organisations that require statehood, meeting Beijing’s expectations. Given the post–Cold War shifts in U.S.’s Taiwan policy and the strains in cross-strait and China–U.S. relations after Lee Teng-hui’s 1995 U.S. visit, Clinton’s clear, public restatement was crucial to the healthy development of bilateral ties.

It was a profound honour to witness this moment firsthand.

The second occasion came in 2001, when then–Senator Joe Biden, chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, planned a visit. Early that summer in Washington, I met my old friend Frank Jannuzi, Biden’s aide for East Asian affairs. He said the senator would stop in Shanghai and Beijing and hoped to meet young people, and asked whether a visit to Fudan and a conversation with our students could be arranged. I told him that the Centre for American Studies would be delighted to host the delegation.

On the morning of August 7, Biden arrived at the Centre for American Studies with three fellow senators and Jannuzi. After a courtesy call with university leaders, they moved to a large classroom for a dialogue with the Centre’s faculty and students. Each senator was slated to speak for 15 minutes, followed by Q&A. Biden spoke first—and for about half an hour—covering three themes.

First, he offered his outlook on China’s trajectory, expressing the view that China would continue along the path of socialism with Chinese characteristics. Second, he addressed Taiwan. He noted that the delegation had stopped in Taipei under the framework of the Taiwan Relations Act, reflecting U.S. security concerns, but reaffirmed adherence to the One-China policy and support for a peaceful resolution. This was early in the George W. Bush administration, which had taken a more pro-Taiwan line; President Bush had said the United States would do “whatever it took” to help Taiwan defend itself. Biden stressed that the U.S. had no defence treaty obligating it to fight for Taiwan and regarded that statement as unwarranted. He added that in his meeting with Chen Shui-bian, he had made clear that any bid for independence would carry consequences to be borne only by Taiwan.

Third, he addressed arms control and non-proliferation, stressing that the United States should pursue diplomacy and negotiations to resolve North Korea’s missile program, work with Russia on the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty, and ensure transparency in the development of the National Missile Defence system, emphasising that it was not aimed at China.

After the session, I asked if this was his first time in China. With evident pride, he said he had first visited in 1979 and had met Deng Xiaoping.

The third event was President Barack Obama’s 2009 visit to China. Early in his administration, amid the global financial crisis, Washington urgently sought Beijing’s cooperation, making stronger bilateral ties a priority. Obama travelled to China in November 2009, the first U.S. president to visit China in his first year since the establishment of diplomatic relations.

Shanghai was his first stop. A highlight was a dialogue with students from several universities, including Fudan University, held on the afternoon of November 16 at the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum in Pudong. The discussion was moderated by Fudan University President Yang Yuliang. Before the event, I was invited by the university to brief students from Fudan and other participating institutions on the United States and China-U.S. relations to help them prepare.

That afternoon, I, along with several colleagues, attended as young faculty representatives from the Centre for American Studies. As the first African American president in U.S. history, Obama naturally drew intense curiosity. Careful observation during the event left me several clear impressions.

First, he struck a generally positive tone toward China and the bilateral relationship. Unlike some U.S. politicians who adopt a patronising stance, Obama showed respect for China’s development achievements and desire for cooperation. Second, his views on international affairs were comparatively progressive. In contrast with his predecessor George W. Bush’s inclination toward militarism and unilateralism, Obama emphasised international cooperation and global governance. Third, he came across as approachable. After the event, he waved to the audience as he headed for the exit. When several students in the front row reached out, he stopped at once to shake their hands. As more students followed suit, Obama didn’t simply walk on; he turned back and moved along the front row, shaking hands all the way before finally waving goodbye. He clearly appreciated the students’ warmth—a personable manner that reflected the culture of American electoral politics.

The fourth event was Dr Henry Kissinger’s visit. On 2 July 2013, the 90-year-old Dr Kissinger, accompanied by Fudan alumnus and former State Councillor Tang Jiaxuan, came to the Centre for American Studies at Fudan University for an exchange with faculty and students. As the centre’s director, I joined his meeting with President Yang Yuliang and later moderated the discussion with teachers and students.

Although I had met this long-time friend of the Chinese people on several earlier occasions, this close interaction left a deeper impression. During the exchange, Kissinger described himself as a neorealist. He argued that every country faces limits in practising democratic ideals and that the United States should not use military force to interfere in other nations’ internal affairs.

When asked about the most unforgettable moments of his life, he recalled the persecution he suffered in Germany before the Second World War, his wartime return to witness the collapse of the German empire, and his experiences in China—observing the achievements of Chinese civilisation and sensing the Chinese people’s deep historical consciousness.

On how the United States should respond to China’s rise, Kissinger noted that even if China’s total GDP caught up with that of the United States, its per capita output would still lag far behind. He added that when he met Chinese leaders in the 1970s, China’s national strength was far weaker, yet its leaders displayed strong confidence. In his view, Americans should respond to China’s rise by working harder and more efficiently to build a better nation. China’s four decades of growth were remarkable, he said, but the United States was not in decline. The decisive factor in China-U.S. competition, he argued, is which side proves more capable of innovation—and he suggested that China still lacks innovative capacity.

He also stressed that neither China nor the United States can impose its will on the other, and that confrontation would leave both worse off. With much pride, Kissinger remarked that he had known all ten U.S. presidents since Richard Nixon and had discussed with each how to advance China-U.S. relations.

Reflecting on youth across eras, he observed that those raised on printed books tend to be more reflective and thoughtful, while the internet generation has access to far more information but is comparatively superficial. What struck me most was his manner of answering questions: concise and sparing with words, yet precise and penetrating—a hallmark of his distinctive wisdom. The elder statesman clearly enjoyed engaging with young people: planned for one hour, the session ultimately ran almost thirty minutes longer.

The fifth event was the visit of former U.S. President Jimmy Carter. On 11–12 November 2013, I was invited to the Carter Centre Forum on U.S.-China Relations in Atlanta, where I met President Carter—who had established diplomatic relations with China during his term—for the first time. Though 89, he was energetic and clear-minded.

Given his historic role in China-U.S. relations, every Chinese delegate was eager to shake his hand and take a photo. Sensing this enthusiasm, President Carter graciously offered to be photographed with each Chinese attendee, and that afternoon, the Carter Centre arranged individual photos one by one.

I was delighted to receive my photo with President Carter, but I also regretted that this key architect of China-U.S. relations had not yet visited Fudan University’s Centre for American Studies. In early 2014, on learning that he planned to visit China later that year, I contacted Dr Liu Yawei of the Carter Centre to extend an invitation. With strong support from the Party Secretary Zhu Zhiwen and President Yang Yuliang of Fudan University, the visit was successfully arranged.

On the morning of 9 September 2014, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter and his wife visited the Centre for American Studies at Fudan University. University President Yang Yuliang welcomed them in the VIP room.

Perhaps to acknowledge my role in organising the visit, President Carter presented me with the Chinese edition of his newly published book, A Call to Action: Women, Religion, Violence, and Power (SDX Joint Publishing Company), inscribed with his signature.

President Carter then delivered a speech in the centre’s auditorium on China-U.S. relations. He argued that the relationship is the most important diplomatic relationship in the world and should be viewed in historical perspective. While bilateral frictions exist, he said, they are not new and should not be exaggerated in ways that damage ties.

He also urged a broad-minded approach, quoting President Xi Jinping’s line that “The vast Pacific Ocean has ample space for China and the United States,” and adding that the Pacific Ocean is spacious enough not just to accommodate the two countries but also to foster positive relations among them and others.

Carter repeatedly reflected on the historical process he and Deng Xiaoping set in motion to establish diplomatic relations. He stressed that both he and Deng believed China-U.S. friendship and cooperation would help secure prosperity and peace for Asia and the world.

With particular relish, he recounted a story from July 1978: when Dr Frank Press, the U.S. presidential science adviser, led a delegation to China, Deng proposed sending 5,000 Chinese students to the United States. That night, Press phoned the White House for guidance. Carter’s reply was immediate: “Tell Deng Xiaoping he can send 100,000!” The anecdote drew thunderous applause from faculty and students.

Though 90 at the time, Carter spoke with clarity and rigorous logic, and after his address, he engaged actively with teachers and students. Asked about meeting new challenges in China-U.S. relations, he said the youth of both nations are the future of the relationship, warmly encouraging the Chinese students present to study in the United States—especially in his home state of Georgia.

Before departing, President and Mrs Carter walked along the front row to shake hands with each student. In their presence, Fudan’s Centre for American Studies and the Carter Centre signed a memorandum of cooperation.

This proved to be President Carter’s final trip to China. I am grateful that he included our centre on his last visit, leaving us with lasting memories.

Mentors and Friends from Across the Pacific

Throughout my more than three decades in academia, I have come to know many American friends, several of whom have been both mentors and friends. My interactions with them have not only greatly advanced my research but also nurtured lasting transnational friendships. For reasons of space, I briefly introduce a few here.

The first that comes to mind is Professor Harry Harding, my faculty sponsor during a research visit to the United States in 1994. At the time, he was a senior fellow in Foreign Policy at the Brookings Institution and directed the Program for International Studies in Asia (PISA).

I recall his trip to China in July 1993 to interview candidates for the PISA visiting scholar programme. I was fortunate to be selected and to conduct research in Washington under his guidance. Then, at the height of his influence, Harding was a leading figure in American China studies; it was a rare privilege to work with him.

When I arrived in January 1994, he was teaching one graduate and one undergraduate course at George Washington University, both of which I audited. His logical, systematic approach to analysis left a deep impression and shaped my research methodology.

Amid the aftermath of 1989 and the upheavals in Eastern Europe, China-U.S. relations were strained, and American public opinion toward China was notably hostile. Yet Harding maintained a relatively objective and fair stance on China and the bilateral relationship.

My research topic at the time was “U.S. Security Policy in Asia after the Cold War.” Professor Harding recommended relevant articles by American scholars, but I felt that reading alone was insufficient and hoped to interview U.S. experts. He readily agreed, compiled a list of experts, scholars, and former officials, and wrote letters of introduction to each. Guided by that list, I interviewed most of them in Washington, New York, and Boston, and those conversations proved immensely helpful to my research.

On that basis, I completed my research report, which Harding recommended for publication in the Journal of Northeast Asian Studies at George Washington University. It became my first English-language academic publication and greatly strengthened my interest and confidence in writing in English.

After I returned to China in early 1995, I stayed in touch with Harding. He continued to recommend me—then still early in my career—for research projects and conferences, offering vital opportunities for academic exchange, and he actively supported several China-U.S. symposia I organised.

From the standpoint of my academic development, Professor Harding was unquestionably the American scholar who provided me with the most significant support.

The second person is Mike Oksenberg. An influential China scholar who came to prominence in the 1970s, he served on the National Security Council during the Carter administration and played an important role in the negotiations on normalising China-U.S. relations, earning the appreciation of President Carter and National Security Adviser Dr Zbigniew Brzezinski.

In June 1996, a delegation from the American Assembly—led by Leonard Woodcock, the first U.S. ambassador to China—visited our centre for a seminar with Chinese scholars on “China–U.S. Relations in the Twenty-First Century.” Oksenberg, then a Stanford professor, was in the U.S. delegation. My remarks at the seminar caught his attention. Over lunch, he sat with me for a long conversation and, before departing, said he was leading a project on the U.S. alliance system in Northeast Asia after the Cold War and hoped to invite me to join.

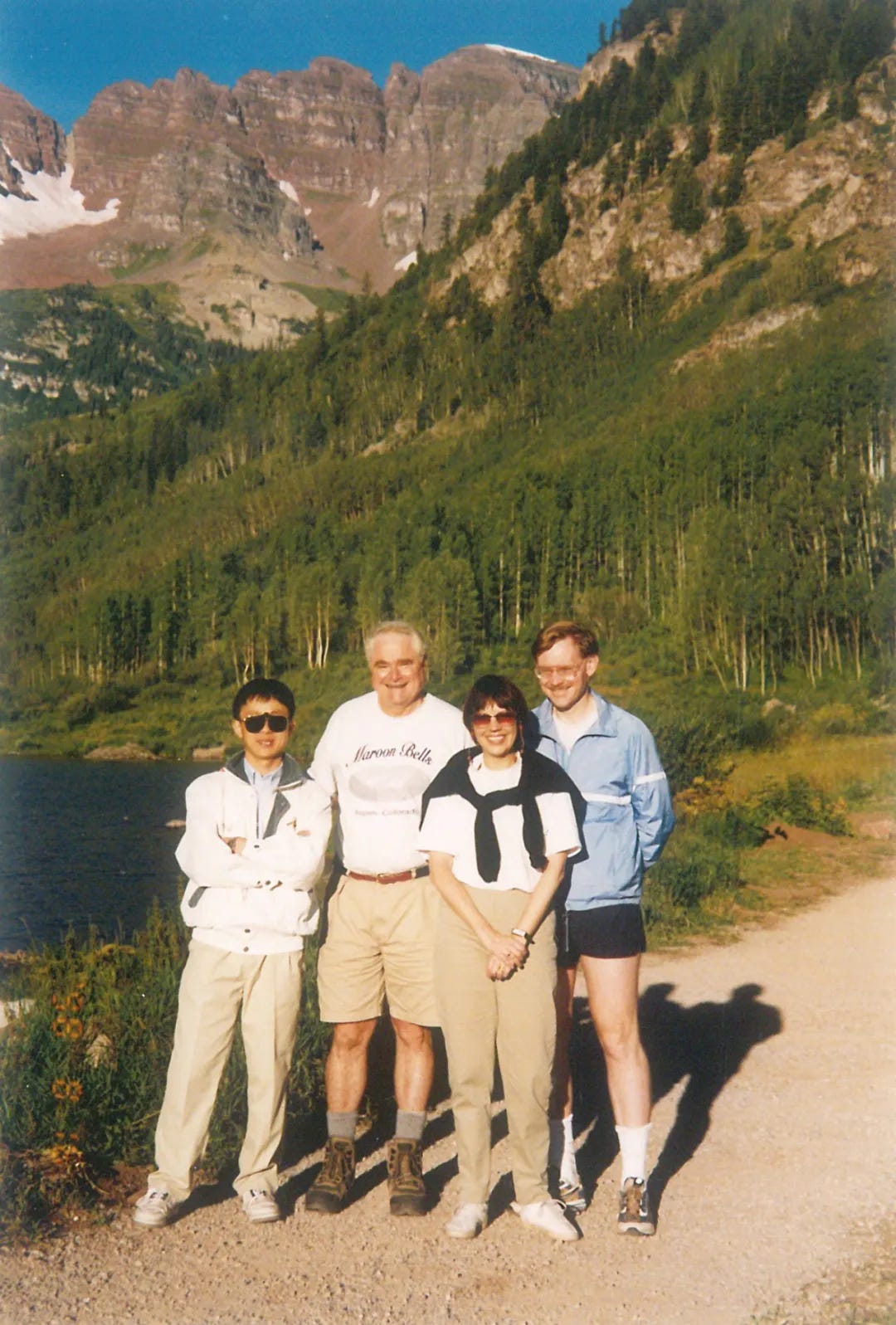

That August, I went to Stanford for the project meeting. The three-year initiative (1996–1998) met annually at Stanford; in 1997, I also spent two months there as a visiting scholar. I still recall that Thanksgiving, when Oksenberg invited me to dinner at his home. He asked about my hometown—Yuexi County, Anhui Province—and expressed a strong wish to visit. Oksenberg told me he was deeply interested in rural China’s development and governance and had worked on a rural project in Zouping, Shandong, but had not yet been to Anhui.

In May the following year, I accompanied Oksenberg and his wife to Yuexi. They met my parents, siblings, and other relatives who still lived in the countryside. We had lunch at my family’s home, walked through the village, and met with county officials. The Anhui trip left a deep impression on Oksenberg and significantly strengthened our friendship.

During those years, I had frequent contact with Oksenberg and gained a deeper understanding of this renowned China expert. He once told me he had grown up in rural America, where his father’s daily questions were, “Have you eaten enough? Have you fed the horses?” That upbringing fostered his enduring concern for rural communities and the lives of farmers.

He became interested in studying China after hearing at university that Mao Zedong was committed to transforming the countryside and improving farmers’ livelihoods. In the late 1980s, with approval from China’s civil affairs authorities, he took part in a rural research project in Zouping, Shandong, making multiple field visits there; he even accompanied President Carter to Zouping in 1997.

Oksenberg held distinctive views on international affairs. He once told me that when the Soviet Union collapsed, many Americans rejoiced, but he privately disapproved. Replacing a bipolar world with a unipolar one, he believed, could make the world less stable by depriving the United States of an external balancing force.

A scholar and former official, Oksenberg had deep ties across American political and academic circles. In American studies and China-U.S. relations, he taught me many things that one cannot learn from books.

It is deeply regrettable that he died of illness in early 2001, at just sixty-two. China lost an old friend who had made important contributions to China-U.S. relations, and I lost a cherished mentor.

The third person is Professor Ezra Vogel of Harvard University. I first met him during the June 1996 seminar held when the American Assembly delegation visited Fudan’s Centre for American Studies. Not long afterwards, when I visited Harvard, he warmly received me, hosting a dinner at the Harvard Faculty Club and inviting several scholars from the Fairbank Centre for Chinese Studies, to whom he kindly introduced me.

We stayed in regular contact and met from time to time in Shanghai, Boston, Washington, Beijing, and elsewhere. In 2006, when I applied for the Jennings Randolph Senior Fellowship at the United States Institute of Peace, he wrote a recommendation letter for me.

Our last in-person exchanges were in 2018. In April, Professor Vogel invited me to deliver a lecture at Harvard’s Fairbank Centre, which he personally chaired. The evening before, he welcomed me and several Harvard scholars of China studies to his home for dinner. We shared takeout from a nearby Chinese restaurant and discussed China and China-U.S. relations in a congenial atmosphere.

In December, at my invitation, Professor Vogel came to Shanghai to join a conference marking the 40th anniversary of China-U.S. diplomatic normalisation, co-organised by Fudan’s Centre for American Studies, the Shanghai Institute of American Studies, and the Shanghai People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. The day before the conference (12 December), he delivered a talk at our centre titled “A Reflection on 40 Years of Sino-U.S. Relations.”

At the time, bilateral ties were strained by the trade war initiated by Trump, and concern about the relationship’s trajectory ran high. Many attendees came specifically for Professor Vogel. When I accompanied him into the lecture hall, it was already packed—every seat taken and listeners standing along the aisles. Warm applause filled the room.

Pleased by the welcome, Professor Vogel announced, to everyone’s surprise, that he would deliver the entire speech in Chinese—prompting another round of enthusiastic applause.

For over an hour, drawing on his research and personal experience, he reviewed the achievements of China’s 40 years of reform and opening up and the profound shifts in China-U.S. relations over those decades. He also spoke candidly about the negative factors weighing on the relationship and his concern about the Trump administration’s China policy. Afterwards, he patiently answered more than ten student questions.

In November 2020, after the U.S. presidential election results were announced, we both joined an online seminar. That was the last time I saw him. Soon after, I learned of his passing. I was shocked and struggled to accept it.

Professor Ezra Vogel had a deep attachment to China. He began studying the country in the 1960s and, in the 1980s, spent more than six months in Guangdong conducting fieldwork on reform and opening up. After retiring in 2000, he devoted a decade to writing Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China.

Although his research encompassed both China and Japan, his fascination with—and commitment to—China far exceeded that toward Japan. His approach to understanding China did not rest on American models or experiences, but on China’s own environment and conditions.

Professor Vogel often remarked that governing a country as vast as China is no easy task. For that reason, he placed great emphasis on how China designs its institutions and sets development strategies according to its own circumstances and needs. This perspective enabled him to view China’s governance and development with relative objectivity, rather than through a U.S.-centric lens.

What was especially admirable was his habit of engaging Chinese scholars as equals, listening carefully to their views and exchanging ideas with genuine humility.

The last person I would like to mention is Dr Robert Zoellick. He has served as U.S. Trade Representative, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State, and President of the World Bank, and he wields significant influence in both American political and business circles. With long experience engaging China, he offers distinctive and incisive insights into China’s development and China-U.S. relations.

I first met him in the summer of 1998 at a seminar in Aspen, Colorado, where Professor Oksenberg introduced us. At the time, he was CEO of the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Although not a China specialist per se, he had a strong interest in China, and we found considerable common ground in conversation.

I recall that in 2000, when I was a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution, he joined George W. Bush’s presidential campaign. On one occasion when we met, he explained to me the Republican Party’s position on Taiwan as set out in its campaign platform.

After the 2000 election, he entered the Bush administration, serving as U.S. Trade Representative and then Deputy Secretary of State, and later became President of the World Bank. During those years, we had little contact.

We met again in May 2013, when I invited him to the Shanghai Forum at Fudan University. On 25 May, we held a dialogue on China-U.S. relations at the Centre for American Studies. Dr Zoellick reviewed his early engagements with China, shared his impressions of the country and its officials, traced the history and current state of bilateral ties, and offered suggestions for China’s development. He also described leading high-level dialogues with China during his tenure as Deputy Secretary of State.

On that occasion, I invited him to my home for dinner. Before the meal, we took a long walk in my neighbourhood and spoke at length. On later visits to Washington, I called on him several times, and he was always willing to meet.

Dr Zoellick is an articulate interlocutor. He understands the workings of U.S. politics and institutions, follows international political and economic developments closely, and brings both historical perspective and breadth of vision. Every conversation with him has been rewarding.

In March 2025, he returned to the Centre for American Studies for the launch of the Chinese edition of his book America in the World: A History of U.S. Diplomacy and Foreign Policy. The work reflects tremendous effort and dedication. Using a panoramic narrative, it surveys U.S. diplomatic thought, practice, and traditions from the nation’s founding to the twenty-first century, distilling five enduring traditions: the need for U.S. dominance in North America, the importance of free trade, the value of alliances, public and congressional support, and America’s purpose.

Dr Zoellick expressed great satisfaction with the Chinese edition’s publication, and the audience exchange that day was lively. Yet, against the backdrop of Donald Trump’s return to the political stage, he, long a moderate Republican, also voiced deep concern about the United States’ trajectory and international affairs.

Epilogue

Time flies, yet memories endure like gold. The treasures of the past remind us where we began and illuminate the road ahead. Looking back over three decades, I feel fortunate to have grown with an exceptional institution like the Centre for American Studies—and even more fortunate to have come of age in a promising era. China’s reform, opening up, and ongoing progress have created invaluable opportunities for the Centre for American Studies and for me personally.

Now, at the Centre’s 40th anniversary and amid new missions in a changing world, we as a national leader in American studies are keenly aware of our responsibilities. With resolve and a spirit of service, we must press forward with courage. Only then can we honour our predecessors’ hopes, uphold the nation’s trust, and write a new chapter in the Centre’s story.

"For that reason, he placed great emphasis on how China designs its institutions and sets development strategies according to its own circumstances and needs. This perspective enabled him to view China’s governance and development with relative objectivity, rather than through a U.S.-centric lens." I'd just like to pick up on this, and maybe it's the translation rather than the original. Still - let us press on.

How can this be? It seems to me that "objectivity", in Chinese, is 客觀, literally - to view as a guest, or an outsider. To place "great emphasis...according to its own circumstances and needs" is almost quintessentially subjective, that is, 主觀, to view as it you were the master or the centre. "According to its own circumstances and needs" can only mean, in this instance, the circumstances and needs as understood by the Chinese government/state/people.

In this case - an analysis of Chinese institutions and development strategies - a "US-centric lens" would be more akin to viewing as a guest. I reject the proposition that to use a US-centric lens would be subjective because Vogel is an American: if so, does a Chinese scholar who uses a US-centric lens become objective, because he is not an American and the lens is not his own? This is patently not the implication to be derived. Objectivity and subjectivity are to be reckoned with respect to the activity being studied, not the identity of the researcher.

If Vogel had, on the other hand, viewed Chinese institutions and development strategies through an objective lens, he would have needed to do so in a reflexive manner, looking not at how the Chinese government/state/people understood China's 'own circumstances and needs', but what those needs were in reality, or ought to be in reality. While subjective in its own way, perhaps, a US-centric lens might have brought him closer to the mark. Somehow, I don't think that's what Vogel did, or at least not as to warrant such praise. Maybe I am wrong!

This is the sort of fuzzy logic to the idiomatic use of the Chinese language that prevents a very clear-eyed vision of China from those on the outside, and indeed to those on the inside.

On the one hand, if you don't know any Chinese, it is quite impossible to understand China: with that proposition I agree.

On the other hand, if you are a Chinese as a second (or foreign) langauge speaker, the idiomatic which is driven into you can and often does short-cut reflexive thought. I know of American Chinese learners, born in the US, who once used 'motherland' 祖國 to refer to China: prompting the (predictable) sardonic reply from their instructor: you're born in the US! Where is your motherland?

It is the truly native speaker who has also internalised the need to be reflexive who can talk out of both sides of his mouth. But what use is such a person? He appears honest to nobody, peculiarly, perhaps, because he is: 兩面不是人.

Here endeth the musing.

That's all in the past now. As are the exchanges of the 19th century.