Zhou Tianyong's economic reform agenda

Former Central Party School economist says dismantling institutional constraints is China's ONLY way toward medium-high growth and avoiding poverty.

Zhou Tianyong is Director of the National Economic Engineering Laboratory at Dongbei University of Finance & Economics and Director of the Economic Accounting and Innovative Development Committee, China Society of Economic Reform (CSER). He is also former Deputy Director of the Institute of International Strategic Studies, Party School of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China (National Academy of Governance).

Zhou acknowledges that traditional models in Western economics—Solow, Harrod-Domar, Lewis, and Jorgenson—all suggest that Beijing’s economic growth targets are out of reach, though he attributes such a result to their failure to capture a crucial dynamic: institutional change. To address this blind spot, Zhou and his team developed a new analytical model that treats institutional reform as a quantifiable variable in projecting economic growth. Their research paper was published in Issue 1, 2025 of 财经理论研究 Journal of Finance and Economics Theory.

According to Zhou’s projections, China could maintain an average annual growth rate of 5.5% between 2025 and 2035—yet provided only bold structural reforms are carried out. These include fully removing household registration barriers to population mobility, reforming land and housing markets by making (especially rural) land-use rights tradable and mortgageable, directing the majority of income from rural land transfers to farmers, introducing private capital as the dominant stakeholder in state-owned enterprises, and increasing in the share of wages and household disposable income in GDP.

The well-known economist, selected as one of China’s top ten influential economists in 2024 by Sina, a popular news portal, is known for publicly advocating economic reforms. Absent reforms, Zhou estimates that China's natural growth rate in the next decade would fall to 1.5% and 2.5% during the same period, and the world’s second-largest economy risks economic stagnation and poverty.

Zhou delivered the following speech on December 20, 2024, at an event co-hosted by the Shanghai Development Research Foundation (SDRF) and the Shanghai Foreign Investment Association. The full text remains available on SDRF’s official WeChat blog.

周天勇:经济增长趋势与关键性体制改革

Zhou Tianyong: Economic Growth Trends and Key Institutional Reforms

I. Forecasts for China's Economic Growth

Chinese and international economists and institutions have offered forecasts for China’s economic growth in both the near and long term. International bodies typically project a growth rate of 4.3% to 4.5% for 2024, whereas some domestic analysts present a more optimistic outlook, anticipating that growth could hit 5%.

In 2023, global per capita GDP reached $13,138, while the threshold for high-income status stood at $14,000. Developed economies averaged $48,220 per capita, whereas China’s per capita GDP was $12,681. China stood below both the global average and the high-income benchmark.

In 2024, high-income countries’ GDPs are expected to grow by 1.6%, compared with 4.3% for medium-high growth countries. If countries with medium-high growth and countries with upper-middle-income sustain an average annual growth rate of 3%, global per capita GDP could reach $20,000 by 2035. For China to reach this milestone within 11 years, it will need to maintain a 4% annual growth rate.

II. Major Issues Facing Economic Growth

The first major challenge lies in China’s shifting demographic structure.

Falling birth rates and a rapidly ageing population are exerting sustained pressure on the labour force, leading to a shrinking base of income-generating individuals—a trend unlikely to be reversed by short-term policy interventions. China’s population decline is occurring at a much sharper pace than in South Korea or Taiwan. In those economies, family planning policies have largely taken the form of soft guidelines, such as “three is a bit too many, two is just right,” rather than stringent one-child limits. Having three, four, or even five children is legally permissible.

By contrast, China’s enforcement of a strict one-child policy has contributed to a particularly sharp demographic contraction. Since both the labour force and the income-generating population are cumulative in nature, this demographic shift is set to become the most formidable headwind facing the Chinese economy over the next two decades.

The second major challenge lies in the rise of local government debt and an expanding social security shortfall. Mounting local liabilities, coupled with growing pressure to fund pension payouts, have become a serious source of concern. The contribution base for social insurance is steadily shrinking, even as the elderly population and the number of retirees drawing benefits continue to rise. This growing mismatch between inflows and outflows threatens to deepen over time, posing an increasingly severe problem.

The third challenge is the inefficiency of state-owned enterprises (SOEs). The low profit margin and inefficiency of SOEs further constrain economic growth.

III. Historical Data and Drivers of Economic Growth

I have used several models, including the Solow Growth Model, the Keynesian Harrod-Domar model, the Lewis Dual Sector Model, and the Jorgenson model. The results from these models suggest that China’s economic growth target is unattainable. Therefore, I began considering whether there are alternative ways to drive economic growth.

The historical performance of China’s economic growth shows significant differences in the sources of growth at different stages.

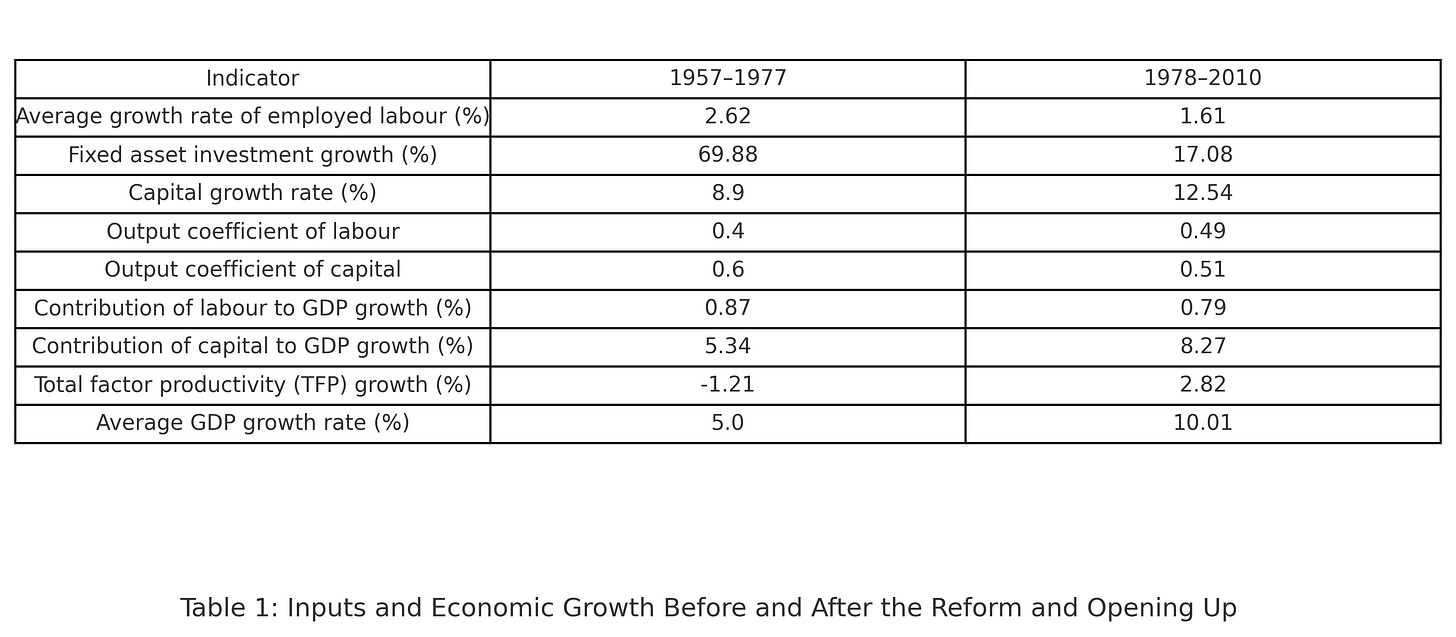

Between 1957 and 1977, the average growth of the employed labour was 2.62%, and fixed asset investment grew by 69.88% annually, reflecting very high investment intensity. However, fixed assets did not always fully turn into effective capital, leading to a significant amount of ineffective capital. As a result, the capital growth rate was only 8.9%. At the same time, total factor productivity (TFP) growth was negative, and the ultimate GDP growth was only 5%.

From 1978 to 2010, the average growth rate of the employed labour force declined to 1.61%, and fixed asset investment fell to 17%. However, the actual capital growth rate reached 12%, and the contributions to economic growth from labour and capital were 0.79% and 8.27%, respectively, calculated by multiplying their respective output coefficients by each factor’s growth rate. TFP increased by 2.82%, bringing overall GDP growth to 10%. By comparison, the earlier period of heavy investment had yielded only 5% growth.

The 10% growth during this period primarily came from the dividends released by institutional reforms rather than technological innovation or external drivers, unlike the productivity gains described in the Solow Growth Model of Western economics.

IV. How to Reflect Institutional Changes in Transition Economies in Economic Models

Economies can be classified as planned, market, or transition economies. Transition economies can be further divided into two types: those that underwent rapid, shock-style transitions, such as Russia and several Eastern European countries, and those that adopted a gradualist approach, as exemplified by China.

Internationally, models employed in both planned and market economies are generally built upon flow variables, using analytically precise frameworks. However, in gradualist transition economies, institutional reforms play a key role in driving economic growth, yet the institutions are not easily incorporated as a variable within the production function. As a result, it is difficult to quantify the precise impact of institutional transformation on economic performance.

In recent years, my research has focused on developing frameworks that treat institutional change as a measurable variable in order to better understand its contribution to economic growth.

My team has developed a model tailored to gradualist transition economies such as China with the aim of analysing and forecasting economic growth while explicitly accounting for the role of institutional change and structural reform. The model treats institutional transformation as a variable that influences economic performance. Its central premise is that institutional shifts, like from a planned to a market economy, can exert a significant impact on growth trajectories.

Model 1 seeks to quantify the impact of institutional changes on economic growth by capturing how institutional reforms affect both the allocation of capital and the efficiency with which it is utilised:

Where:

Qₜ / Qₜ₋₁ = GDP growth rate

Res = Total resources

yᵣ = Share of resources allocated to market-driven sectors

xᵣ = Share of resources allocated to administratively planned sectors

yₚ = Production productivity and demand-side utility in market-driven sectors

xₚ = Production productivity and demand-side utility in planned sectors

Model 2 evaluates the contribution of land and housing assets to economic growth by incorporating their transaction activity and market pricing dynamics:

Where:

Qₜ / Qₜ₋₁ = GDP growth rate

LH = Total area of land or housing assets

r = Transaction rate in the given year

I(ω)ᵣ = Transaction permission indicator (1 = permitted, 0 = not permitted)

P = Market price level

I(ω)ₚ = Market price availability (1 = price exists, 0 = no market price)

These two foundational models can convert institutional changes into measurable variables. Building on these, the production function was adapted and integrated with Keynesian distribution and expenditure frameworks to construct a comprehensive national economic model encompassing supply, distribution, and demand. This model closely reflects China’s economic growth trajectory over recent decades and serves as a basis for projecting future trends.

Looking ahead, growth is expected to be driven primarily by surplus dividends from institutional change, with their release contingent on meaningful reform.

China still has an estimated 100 million surplus workers whose mobility is restricted by institutional barriers. Relaxing the household registration system could unlock this labour potential by facilitating internal migration. A weighted average of agricultural employment across 18 populous countries with per capita GDPs roughly $5,000 below China’s—such as Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Turkey and Malaysia, none of which maintain a household registration system—shows that agriculture accounts for just 10% of total employment. By contrast, agriculture still employs 24% of China’s workforce, according to the National Bureau of Statistics. This 14-percentage-point gap is largely due to household registration-related constraints, including restricted access to urban education and residency.

In the early years of China’s reform and opening up, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) accounted for roughly 80% of total capital, while collectively owned assets made up about 15%. Over time, the SOE share steadily declined, falling to 20% by 2008. This shift, combined with improved efficiency in the non-state sector, contributed over one percentage point to annual economic growth. However, the 4 trillion yuan stimulus introduced in 2009 largely flowed into SOEs, pushing their asset share back up to 40%. Between 2009 and 2023, despite the expansion in SOE assets, persistent inefficiencies resulted in a measurable drag on growth—equivalent to an estimated 0.84 percentage point loss in annual GDP growth.

V. There is No Other Way but Reform to Achieve Long-term Medium-High Growth

1. Significant institutional constraints remain within China’s supply side.

An estimated 130.45 million surplus labourers are currently held back by structural barriers, while underutilised capital constrained by institutional inefficiencies totals approximately 265 trillion yuan. In addition, around 131.5 million mu [87.6 billion square kilometres] of low-utilisation construction land remain locked due to institutional restrictions. The combined value of urban and rural land and housing resources, calculated at shadow prices, was roughly 700 trillion yuan in 2023 and is projected to reach 1,000 trillion yuan by 2035.

2. On the demand side, untapped potential lies in urbanisation, the shift toward industrial employment, and consumption of durable goods, automobiles, and housing.

In 2022, the average urbanisation rate among major developing countries at a similar stage of development was 80.1%. By comparison, 65.22% of China’s population lived in urban areas, yet only 48% of these residents held an urban household registration. By 2035, the urbanisation strategy should aim to raise the urban resident population share to 82% and grant urban household registration to a portion of the rural-registered population already residing in cities.

Prior to 2022, the benchmark non-agricultural employment rate among developing countries stood at 90.28%, while China’s rate was 75.92%, reflecting a gap of 14.36 percentage points. By 2035, the target should be to raise the non-agricultural employment rate to approximately 92%. Excluding factors such as natural deaths, urban industrial and service sectors will need to absorb an additional 107.57 million workers through employment transfers.

In terms of durable goods ownership, China’s rural population remains in the mid-stage of industrialisation, while both urban and rural residents are still in the early phase of becoming an automobile society. By 2035, rural and urban resident populations are expected to reach higher levels of urbanisation and industrialisation, advancing toward a more prosperous society. Household car ownership should approach levels typical of mature automobile societies, reaching around 160 vehicles per 100 households.

In the construction sector, housing conditions for rural, township, and suburban residents remain at the early to mid-stages of industrialisation, while urban residents without urban household registration have yet to fully share in the benefits of urbanisation and construction modernisation. As urbanisation advances, residential buildings may enter a renewal phase earlier than expected. Living environments are likely to shift from high-rise developments to more horizontally oriented layouts, with gradual improvements in housing functionality. Aesthetic and comfort standards in renovations, appliances, finishes, and materials are set to rise. Building quality, including earthquake resistance, fire safety, insulation, and elevator performance, is expected to improve, accompanied by large-scale renewal and retrofitting of ageing residential communities.

3. Implement land and housing reform to make land-use rights tradable and mortgageable

While maintaining state and collective ownership of land, the terms of use for various land categories should be extended to strengthen protections for urban and rural land-use rights.

Legal entities and individuals should be permitted to engage in transactions, pricing, equity participation, leasing, mortgaging, and inheritance involving land-use rights. Both primary and secondary markets for urban and rural land should be opened to facilitate such activity. At the same time, land-use regulations and construction planning should be adjusted to reflect evolving social needs and align closely with the market.

Full registration, rights confirmation, and certificate issuance shall be implemented for houses built on land with usage rights held by natural persons and legal entities in both urban and rural areas.

The current system restricting market transactions of urban and rural land, as well as rural residential properties, should be reformed to establish a competitive land and housing market. Market access should be broadened, pricing mechanisms aligned with market forces, and land and housing assets made tradable and eligible for mortgage.

4. Implement household registration and state sector reform

Household registration restrictions should be fully lifted to allow children to access education in the cities where their families work. At the same time, providing diversified housing supply to reduce living costs and improving social security coverage for migrant populations are essential. Together, these measures would support the transfer of labour from low-productivity rural agriculture to higher-productivity urban industrial and service sectors.

SOE reform should deepen through an overhaul of employment systems. Fiscal management should be restructured by placing county-level finances under direct provincial oversight and township finances under county administration. In parallel, merging and downsizing agencies and streamlining non-productive personnel would improve SOE efficiency and the effectiveness of public service delivery.

The share of state-owned assets in total capital should be reduced from 40% in 2023 to below 20%. Alternatively, reforms could follow the Temasek model by using profit margins as the primary metric for SOE performance. Another approach would be to adopt asset profitability as the core evaluation criterion, with most SOEs required to meet or exceed the average return on total capital. For non-monopoly SOEs, mixed-ownership reform could also be expanded to introduce private capital, which is more efficient, as the dominant stakeholder.

5. Distribution system reform

The share of household disposable income in GDP should gradually rise from 43.86% in 2023 to 65% by 2035, including 10 percentage points derived from transfer payments in areas such as education, healthcare, housing, and childbirth. Over the same period, the government’s share of disposable income should be reduced from approximately 33% to below 30%.

The majority of income from collectively owned land transfers in rural areas should be allocated directly to farmers. When farmers relocate to urban areas, they should be permitted to sell their rural homesteads and houses at market prices, with the post-tax proceeds going entirely to the farmers themselves.

Capital should be encouraged to flow into rural areas to allow farmers land development rights and enable them to earn non-agricultural income from their land.

Local governments have already accumulated substantial revenues from rural land transfers. Nationally, efforts should focus on providing affordable housing for university graduates residing in urban areas, as well as for urban residents who hold rural household registration.

Policies should aim to increase the share of permanent employment and raise the per capita disposable income of urban households holding rural registration. At the same time, efforts are needed to narrow the wage gap between private sector employees and competitive benchmark wages in equity partnerships, limited liability companies, and joint-stock enterprises. Policies should also support an increase in the share of wages in GDP.

6. Demand-side institutional reform

By 2035, the share of household consumption in GDP should rise from 30% in 2023 to 55%. At the same time, government consumption should gradually decline from approximately 20% to 10%, while increasing transfer payments for education, healthcare, and housing to raise their share from 8% to 20%.

In addition, public spending should be expanded in key welfare areas such as public education, healthcare, pension subsidies, housing security, and childbirth support. As a share of GDP, expenditures in these categories should increase from their 2022 levels—3.27%, 1.87%, 2.00%, 0.57%, and 0.42%, respectively—to 6%, 5%, 2%, 4%, and 3% by 2035.

The share of investment by the state sector—including state-owned non-financial enterprises and government spending on infrastructure and public facilities—should be reduced from 56% to 25%, while the share of investment from the non-state sector should be increased from 44% to 75%.

In terms of external economic circulation, the share of exports in GDP should gradually rise from 18% to 25%.

7. Average annual economic growth could reach approximately 5.5% between 2025 and 2035 if reforms are implemented.

China must relax, invigorate, open up, and reform key institutions including administrative governance, land, SOEs, and population mobility. In the absence of institutional reform, the economy’s natural growth rate is projected to range to between 1.5% and 2.5% between 2025 and 2035, with technological progress and total factor productivity contributing 0% to 0.5%. Comprehensive reforms across supply, distribution, and demand systems could add an estimated 3.5 percentage points to growth. Imports, exports, and foreign direct investment are expected to contribute between -0.5% and 0.5%. Combined, these elements could support an average annual growth rate of approximately 5.5%.

Opportunities are fleeting and, once missed, may not return. A failure to act decisively risks consigning China to economic stagnation and poverty. Development remains the driving force of China’s modernisation, while reform is the decisive factor shaping its future. By advancing deep structural reforms—such as the market-based allocation of production factors, making land-use rights tradable and mortgageable, and overhauling institutions related to distribution and demand—China can sustain medium-high growth for more than a decade. This would enable the country to confront the challenges of an ageing population, escape the middle-income trap, expand national wealth, and transition into the ranks of high-income economies. With continued reform, China is positioned to basically realise modernisation by 2035 and become a prosperous modern country by 2049.

Yes, I've long admired Zhou Tianyong. He has been saying things like this for years. Peasants rights -- they need to get the full benefits from the value of their land. Business people's rights need to be respected too. Over the years I have learned much from his writing. Some of them I have translated or summary translated on my translation blog.

2024 Party School’s Zhou Tianyong: Protecting Property Rights of Small Business is Fundamental for Economic Recovery https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2024/09/30/2024-zhou-tianyong-protecting-property-rights-of-small-business-is-fundamental/

2024: Zhou Tianyong on Detaining Businesspeople to Extort Fees to Boost Local Government Revenues (censored) https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2024/09/30/__trashed-2/

2021 Zhou Tianyong: Understanding Mixed Economy Distortions in the Chinese Economy

https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2022/10/30/2021-zhou-tianyong-understanding-mixed-economy-distortions-in-the-chinese-economy/

2022: Zhou Tianyong – Understanding China’s Economy Needs Both Structuralist Approach and Dualistic Institutional Vision https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2022/10/29/2022-zhou-tianyong-understanding-chinas-economy-needs-both-structuralist-approach-and-dualistic-institutional-vision/

2005: Zhou Tianyong: Reform of the Chinese Political Structure

https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2017/08/08/2005-zhou-tianyong-reform-of-the-chinese-political-system/

2005 Zhou Tianyong: To Increase Peasant Incomes Which is More Important, Boosting Funding or Rights? https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2016/10/14/%e8%8b%b1%e6%96%87%e7%bf%bb%e8%af%91%ef%bc%9a%e5%91%a8%e5%a4%a9%e5%8b%87-%e7%aa%81%e7%a0%b4%e5%8f%91%e5%b1%95%e7%9a%84%e4%bd%93%e5%88%b6%e6%80%a7%e9%9a%9c%e7%a2%8d/

How much can China move in the direction Zhou Tianyong wants it go? The Chinese Communist Party's worries about social and stability and the possible weakening of the Party's control and management of Chinese society constrains possible changes.

I wonder if a Marxist would worry about political consequences of thoroughgoing economic reform. Here are passages from Marx's 1859 "A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy". Under Party Secretary General Xi Jinping, Chinese universities have been opening institutes for the study of Marxism with Chinese characteristics of course. I wonder how much this passage from Karl Marx is stressed and understood. https://gaodawei.wordpress.com/2022/01/13/xi-jinping-continue-sinicizing-and-adapting-marxism-to-our-times/

📘 English

In the social production of their existence, men inevitably enter into definite relations, which are independent of their will, namely relations of production appropriate to a given stage in the development of their material forces of production. The totality of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which arises a legal and political superstructure and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness. The mode of production of material life conditions the general process of social, political and intellectual life. It is not the consciousness of men that determines their existence, but their social existence that determines their consciousness.

📗 中文翻译(官方译文)

人们在自己生活的社会生产中发生一定的、必然的、不以他们的意志为转移的关系,即同他们的物质生产力的一定发展阶段相适合的生产关系。 这些生产关系的总和构成社会的经济结构,即有法律的和政治的上层建筑竖立其上并有一定的社会意识形式与之相适应的现实基础。 物质生活的生产方式制约着整个社会生活、政治生活和精神生活的过程。 不是人们的意识决定人们的存在,相反,是人们的社会存在决定人们的意识。

Zhou's proposed reforms are not fundamental. This is not a criticism. His proposals are steps on the long-traveled path of ensuring that China does not engage in planned socialism, in socialist planning, in moving toward equality and liberated work for all.

And his discussion is serious. In contrast, the praises of alleged Chinese socialism by some "socialists" in the West, for example at Friends of Socialist China, look truly ridiculous.