Bureaucratic Lapse, Not Bioterror: The Overblown Fungus Smuggling Case

Treating two plant pathologists with no paperwork as though they were biowarfare saboteurs is an exercise in political theater, not prudent security

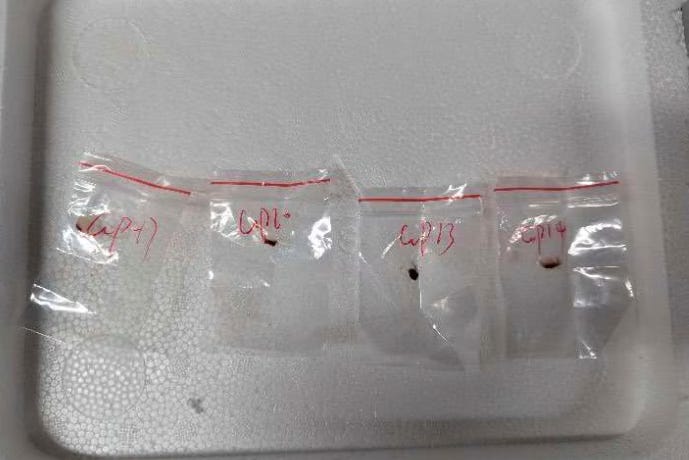

In June 2025, U.S. prosecutors charged1 two Chinese researchers – Yunqing Jian, a University of Michigan postdoctoral fellow, and her partner Zunyong Liu of Zhejiang University – with conspiracy and smuggling for bringing a plant fungus into the country. Liu arrived at Detroit Metro Airport in July 2024, carrying four plastic bags of Fusarium graminearum hidden inside wadded tissues. When questioned, he initially feigned ignorance but soon admitted he had concealed the samples “because he knew there were restrictions on the importation of the materials,”2 and that he planned to clone them and conduct research in Jian’s lab at the University of Michigan. In other words, he knowingly skipped the legal paperwork required to import a regulated organism. The fungus was confiscated, Liu was deported to China, and nearly a year later, Jian was arrested in Michigan to face charges. Both were accused3 of smuggling goods, making false statements, visa fraud, and related offenses.

Federal authorities painted the incident in ominous hues. The Department of Justice press release4 trumpeted Fusarium graminearum as a “dangerous biological pathogen” and even hyped it to a “potential agroterrorism weapon” capable of devastating wheat, corn, and other crops. An FBI special agent described5 the pair’s actions as an “imminent threat to public safety”. A U.S. Attorney went so far as to highlight6 Jian as “a loyal member of the Chinese Communist Party” and declared the case “of the gravest national security concerns,” alleging the two intended to use an American lab to further a malign “scheme”. In short, what might otherwise appear to be a customs violation in service of academic research was portrayed as a potential act of agro-sabotage against the “heartland of America”7.

A Common Crop Pathogen, Not a Bioweapon

Lost in the incendiary rhetoric is the reality of Fusarium graminearum itself. Far from being an exotic new bioweapon, this fungus is a well-known agricultural pathogen that already exists in the United States. Plant disease experts note8 that Fusarium graminearum outbreaks occur naturally in “dozens of U.S. states” – essentially anywhere wheat and barley are grown – and the pathogen has been entrenched in the country for at least 125 years . “We’re not talking about something that just got imported from China,” emphasizes Dr. Caitilyn Allen, a plant pathology professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “People should not be freaking out,” she told9 ABC News. In fact, the U.S. Department of Agriculture does not even list Fusarium graminearum as a top agroterror threat of concern , despite the DOJ’s dramatic language.

To be sure, the fungus is destructive to crops, so American farmers and scientists take it seriously; the U.S. government spends money each year to research and combat this disease. But precisely because it’s a familiar enemy, the U.S. has developed tools to manage it (resistant crop varieties, fungicides, forecasting models) and has a whole initiative devoted to fighting it. “It’s one of the ones that would be at the lower end of the spectrum for risk,” said10 Dr. Paul Esker of Penn State University, noting that American agriculture is “well-versed” in handling it . In contrast to truly novel pathogens or foreign pests, Fusarium graminearum doesn’t rank near the top of experts’ worry list. As Dr. Gary Bergstrom, another plant pathologist, put11 it, “Compared to some other things, I don’t think the risk is as high. It’s not zero, but it certainly wouldn’t be as much concern as… diseases that we don’t have now” .

Crucially, context matters for any biosecurity threat. Prosecutors implied the couple’s smuggled strains might be unusually virulent or weaponizable, but no evidence of that has been made public. Experts note12 that to deem these samples an “agroterrorism” danger, one would need to show they were a particularly aggressive or toxin-producing strain beyond what already circulates in U.S. fields . So far, that hasn’t been demonstrated. Absent such evidence, sneaking in a few fungus samples – while certainly illegal and ill-advised – is worlds apart from plotting an agricultural WMD attack. “The biggest group of plant pathogens are fungi,” notes Dr. Allen, and research on them is essential to protecting crops. Indeed, she surmises that the confiscated sample was likely headed to the University of Michigan’s plant disease resistance lab, which is exactly where one would study how to better control Fusarium and help farmers. Ironically, the work Jian and Liu intended to do – had they gone through proper channels – contributes to U.S. crop protection efforts rather than threatened them.

Cutting Corners on Paperwork vs. Criminal Intent

Why would two trained scientists resort to stuffing lab samples in a suitcase instead of obtaining permits? The picture that emerges is not of spies on an agroterror mission, but of academics cutting corners to expedite research. The FBI affidavit itself notes13 the couple had been communicating about “shipping biological material ‘commonly used for academic research’” well before Liu’s trip. In fact, they successfully smuggled plant seeds into the U.S. in 2022 using international mail, according to that affidavit. This suggests a pattern of bypassing red tape to acquire research materials, likely driven by convenience or urgency rather than malicious intent. Jian and Liu both specialized in plant pathogens – their mission are about understanding crop diseases, not spreading them .

From the evidence presented publicly, their motive appears to have been scientific inquiry (albeit pursued recklessly) rather than sabotage. Liu admitted to authorities that his goal in bringing the fungus was to “conduct research on”14 it in his girlfriend’s university lab, and there’s no indication he attempted to release the organism outside the lab setting. The duo’s mistake – a serious one – was trying to shortcut biosafety rules. The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) requires15 researchers to obtain a phytosanitary permit to import foreign plant pathogens, so that proper containment protocols are in place. Jian and Liu evidently decided to skip this process. Perhaps they feared a permit would be denied or delayed; perhaps they didn’t want the hassle of paperwork and inspections. Regardless, sneaking in samples violated both the law and scientific ethics, even if their reasons were simply impatience or overconfidence in handling the material themselves. As one University of California, Berkeley biologist noted16 to the Associated Press, sending biological materials without authorization “doesn’t strike me as dangerous in any way. But there are rules to ship biological material” and those rules exist for good reason .

Importantly, such corner-cutting is not unheard of in the scientific community, especially for benign or routine materials. The reality is that informal sharing of research samples across borders is fairly common, despite being against regulations. “Researchers frequently use informal methods to share common samples like plasmids to avoid delays that can cripple a research project,” observed17 the Berkeley scientist– calling it a widespread practice in international science. In many labs, junior researchers quietly mail or carry small samples without permits (with supervisors sometimes turning a blind eye), particularly if they judge the materials to pose minimal risk. None of this excuses Jian and Liu’s actions – rules and safety protocols exist for a reason, and even well-intentioned scientists can cause harm by moving pests or pathogens improperly. But viewing their case in this light suggests it was a run-of-the-mill violation amped up by extraordinary rhetoric, rather than a nefarious conspiracy. The real issue, once again, is a customs violation, not a plot to destroy American agriculture.

An Overwrought National Security Response

If the scientific context tempers the alarm, the official response did the opposite, cranking up the volume with references to terrorism and espionage. The Justice Department’s statements and subsequent right-wing media coverage went to great lengths to tie this incident to national security threats. The FBI Detroit office lauded18 the case as a “crucial advancement” in defending the country, and credited its counterintelligence task force with halting “dangerous activities” just in time . Customs officials highlighted19 that one of the suspects was “a researcher from a major university attempting to clandestinely bring potentially harmful biological materials,” framing it as an insidious infiltration of the scientific establishment. And prosecutors repeatedly underscored the defendants’ Chinese nationality and connections: for example, emphasizing that Jian had received some Chinese government research funding and that her laptop contained a statement affirming her Chinese Communist Party (CCP) membership. These facts, while undisputed, were presented in a menacing light – as if a postdoc having a Chinese grant or party membership is tantamount to evidence of terrorism.

That implication is highly dubious. By the CCP’s own count20, nearly 100 million Chinese citizens are CCP members, including many academics, where party affiliation is often a routine requirement for career advancement . In Jian’s case, the University of Michigan noted21 that it had received no Chinese funding related to her work, and her lab was supported by U.S. funding22. In other words, she was integrated into mainstream American research. Yet the FBI and DOJ chose to spotlight her loyalty oath to the CCP – a move one might view as playing to political fears rather than reflecting something uniquely sinister about her behavior. It is reminiscent of an earlier era’s loyalty tests; being a Party member does not prove one is acting as a foreign agent. The Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs pointedly criticized23 the U.S. for its “political manipulation” in this case, stressing that China tells its scholars to obey local laws but opposes casting academic exchanges in an ideological, confrontational light .

The timing and context of the prosecutions bolster the impression of politicization. Jian’s arrest in June 2025 came almost a full year after the incident – right as U.S. authorities were unveiling a spate of similar cases involving Chinese nationals. Also in early June, another visiting Chinese scholar in Michigan, Chengxuan Han, was arrested for mailing unpermitted research materials (common roundworms and DNA plasmids) to herself and colleagues. In Han’s case, too, officials hyped the charges: the DOJ press release even headlined24 her as an “Alien from Wuhan” caught smuggling biological materials, transparently tapping into COVID-era anxieties. It’s not implausible to imagine Jian’s delayed arrest was likely politically motivated to coincide with other cases in the anti-China campaign, creating a drumbeat of Chinese biosecurity scares. The FBI and some right-wing media and influencers then explicitly linked these unrelated incidents – a plant fungus here, some lab worms there, even an out-of-state voter fraud case involving a Chinese student – as if they formed a menacing pattern of Chinese subversion centered on one university. It has all the hallmarks of a fear campaign: disparate events stitched into a narrative of pervasive threat.

This narrative did not arise in a vacuum. It comes amid rising U.S. government hostility toward Chinese scholars and research ties. Just days before these arrests, Secretary of State Marco Rubio announced visa crackdowns on Chinese students, accusing them of stealing technology and vowing to “aggressively revoke” visas, especially for those with any CCP affiliation or studying sensitive fields. In Congress, hardliners have pressured universities to cut academic partnerships with China; under that pressure, the University of Michigan itself had just closed25 its joint institute with Shanghai Jiao Tong University earlier in 2025. Now U.S. lawmakers seized on the fungus case to argue26 that “Chinese researchers tied to the PRC defense research and industrial base have no business in U.S. taxpayer-funded research” and to lambast U-M for lax security. The whiff of McCarthyism is hard to ignore: the focus on the researchers’ nationality and political background, rather than on the act itself, suggests the real offense in the eyes of some is simply being Chinese in a sensitive field. Indeed, the now-defunct “China Initiative”27 – a Trump-era DOJ program nominally targeting economic espionage – had infamously ensnared numerous academics of Chinese descent for minor infractions, only to collapse under accusations of racial profiling and lack of spy convictions. This fungus episode appears to check all the same boxes as the infamous China Initiative: an exaggerated threat description, heavy-handed charges, and inflammatory commentary about communist loyalties – all for what essentially amounts to violating import protocols.

Conclusion: A Geopolitical Overreaction

None of this is to deny that Jian and Liu were wrong to flout U.S. biosecurity rules. In an age of globalized research – and globalized diseases – one cannot simply trust personal judgment to trump regulations. Even a commonly found fungus could carry a surprise or a more virulent strain, so authorities are right to enforce permits and punish willful violations. However, the disproportionate framing and fallout of this case serve no one well. Treating two plant pathologists with poor paperwork as though they were biowarfare saboteurs is an exercise in political theater, not prudent security. The harsh rhetoric and extreme charges (such as labeling the fungus an “agroterrorism weapon” and invoking visa fraud over a research visit) strongly suggest that geopolitical tensions with China drove the response more than the actual level of danger did. As the American Phytopathological Society observed, regulation of pathogens is about “doing science safely and responsibly,” not about demonizing scientists .

By irresponsibly politicizing this incident, U.S. officials risk undermining scientific collaboration and chilling the very research that protects our food supply. The lesson here should have been that even well-meaning scientists must follow safety protocols. Instead, the takeaway became a sensational story of Chinese researchers plotting against American crops – a claim that, under scrutiny, wilts like a diseased plant. A more measured approach would acknowledge the wrongdoing (and perhaps levy a modest punishment or fine), without inflating a lab mistake into a national security scare. Unfortunately, in the current climate of U.S.-China rivalry, even a fungus in a test tube can be spun into a symbol of foreign menace. We must guard against such overreactions. Biological security is best served by facts and balance, not fear-mongering. And scientific progress – including fighting crop diseases – is best served by keeping politics from poisoning the well of cooperation. In the end, this case reveals far more about our political spores of distrust than about any literal fungus.

The Washington Post (Annabelle Timsit) – Two Chinese nationals charged with smuggling toxic fungus into U.S. (June 4, 2025) .

NBC News (Tom Winter) - Chinese couple charged with smuggling a biological pathogen into the U.S. (June 4, 2025)

Reuters (Jasper Ward) – Justice Department accuses two Chinese researchers of smuggling ‘potential agroterrorism weapon’ into US (June 3, 2025) .

DOJ Press Release – U.S. Attorney, E.D. Michigan – Chinese Nationals Charged with Conspiracy and Smuggling a Dangerous Biological Pathogen… (June 3, 2025) .

ibid

ibid

ibid

ABC News (Julia Jacobo) – What to know about Fusarium graminearum, the biological pathogen allegedly smuggled into the US (June 5, 2025) .

ibid

ibid

ibid

ibid

The Washington Post (Annabelle Timsit) – Two Chinese nationals charged with smuggling toxic fungus into U.S. (June 4, 2025).

ibid

American Phytopathological Society – FAQ: Fusarium graminearum and Fusarium Head Blight (Scab) (2023)

Associated Press (Ed White) - US arrests another Chinese scientist for allegedly smuggling biological material (June 10, 2025)

ibid

DOJ Press Release – U.S. Attorney, E.D. Michigan – Chinese Nationals Charged with Conspiracy and Smuggling a Dangerous Biological Pathogen… (June 3, 2025) .

ibid

Xinhua News Agency - CPC grows stronger as membership exceeds 100M (June 30, 2025)

University of Michigan - University Statement on Chinese Research Fellow (June 3, 2025)

South China Morning Post – China slams US ‘political manipulation’ as research pair face fungus smuggling charge (June 7, 2025)

DOJ Press Release – U.S. Attorney, E.D. Michigan – Alien from Wuhan, China, Charged with Making False Statements and Smuggling Biological Materials into the U.S. for Her Work at a University of Michigan Laboratory (June 9, 2025) .

University of Michigan - U-M to end partnership with Shanghai Jiao Tong University (June 3, 2025)

Some U.S. Representatives - Letter to President Domenico Grasso, University of Michigan (June 18, 2025)

Politico (Phelim Kine) - DOJ’s ‘China Initiative’ is dead but racial profiling fears are still very much alive (02/24/2022)

Meanwhile at the 11 bio-weapons labs run by the US DOD in Ukraine....

Articles like this are counterproductive to the point they wish to support. It would be better to acknowledge that espionage and similar malign International activities are rampant, always denied by the perpetrators, and always camouflaged as benign. The article should have focused on instructing people, particularly international academics, to understand the responsibilities of government and act respectfully toward those responsibilities.